All photos created by the author.

Nothing beats starting your overtime shift on a nice, clear Taco Tuesday night with your regular partner on overtime, too. You both play rock paper scissors to decide which of your favorite food trucks you’ll be getting dinner at. Your partner is hell-bent on chicken tacos while you’re craving your favorite grouper tacos at Rick’s with the mango salsa. As you throw down rock and she throws down paper, your CAD chirps.

After the initial wave of disappointment that you lost with rock and have to capitulate to chicken tacos, you start to the call. You encounter a ton of construction road work for the evening as they are trying to tear up and fix the locality’s dismal pothole-ridden roads. As you around the bend, you find a small cluster of young individuals standing around a person on the ground. You partner puts the rig in park, and you tap the CAD’s on-scene button. You see a person who is sitting upright on the curb with a crowd around them waving you over with the preverbal concerned and intense wave like a used car lot wacky waving inflatable arm man.

You notice they all have ride-share scooters next to them, and you see one on the ground adjacent to the person sitting on the curb. As you walk up, you meet your patient, Ryan Killian, sitting up and looking over at you while wincing intermittently in pain. He says (with a long and exaggerated delivery), “W..h..a..t..’s….u..p..?” You follow with, “Not much; what did you do?” Ryan begins to answer, but a friend takes over and says that they were on their way to get food when Jason, one of the friends, jumped a pothole on the scooter, and Ryan, who was right behind him, didn’t see it.

The front tire of the scooter went into the pothole, and Ryan went over the handlebars. None of the riders are wearing helmets, including Ryan. You ask if Ryan hit his head, and he shakes his head no and says he landed on his hands. You kneel to start asking questions, assess Ryan, and notice he looks at you but won’t deviate from staying upright. Your partner arrives by your side with the monitor and starts hooking him up.

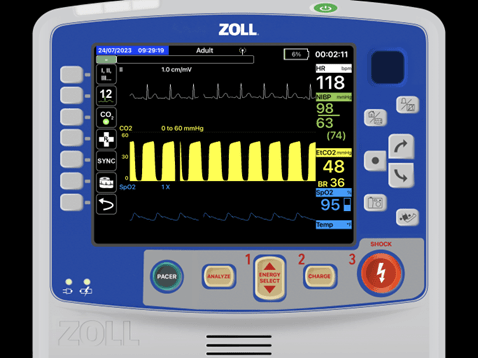

What are some of your differentials based on the presentation, the mechanism, and the situation?

Do the below vital signs change your mind or help stratify your differentials?

Ryan can answer your questions and says nothing hurts except his ego, and he feels the urge not to lean back or bend forward. You notice as he answers your questions and gets longer into a sentence his respiratory depth becomes shallower, and his rate becomes increases. You continue your assessment and deduce he did not lose consciousness; he remembers the event and braced himself with his hands (where you find road rash on the base portion of the palms). The handlebars hit him in the chest on his way down, and he quickly went to the ground.

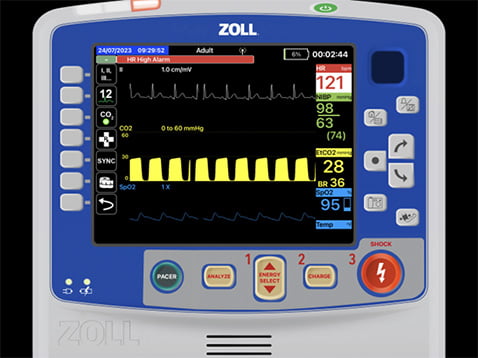

He has no medical history, takes no medications and has no drug allergies. You lift his shirt, and you see what looks like a mild reddening where the handlebar hit, and it’s located about the fourth or fifth intercostal space left side and goes up to his left shoulder. As you continue to ask Ryan questions, his ability to finish sentences without becoming short of breath diminishes. He continues to wince with his words. He says it’s hard to catch his breath and wants to stand up and walk around to see if it gets better. You convince him to stay seated. You continue down your assessment and find the following changes. What jumps out of you?

You explain your findings and convince him to go to the hospital to get checked out. After sitting on your cot for about a minute, he says he can’t catch his breath. “I… Can’t… Catch… My… Breath,” he says and starts to tug and hold his left clavicle. You look at the monitor and auscultate lung sounds again and find absent left lower and significantly diminished left upper lung sounds. Based on the monitor and findings, what is happening?

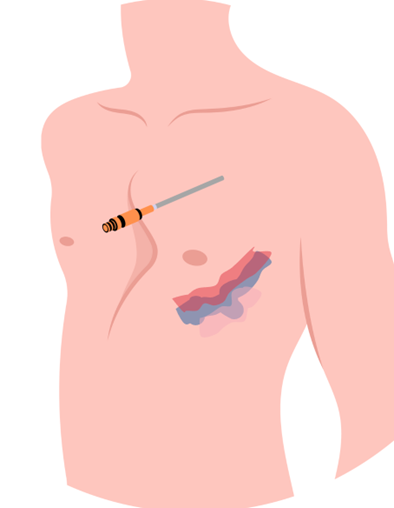

You quickly get up and poke your head through the window to your partner as they are just putting the vehicle into drive. You let them know you’re going to “pop” Ryan’s chest. Your partner quickly looks back and says, “Really?” and then hops out to come in the back and help. You pull your needle out and landmark between the second and third intercostal space mid-clavicular, you wipe the site with an alcohol prep, and then puncture through the skin and roll over the third rib.

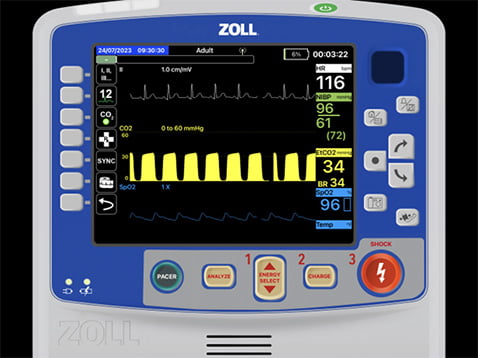

You dive the needle and feel pressure on your finger where you had put it over the end. You pull out the needle while leaving the catheter in and feel a slight pressure change on your thumb. You secure the catheter, glance over at your monitor, and find the following changes. At the same time you notice Ryan looking down at the needle you just placed in the upper part of his thorax. Are you out of the water yet?

Your partner hops upfront and starts for the hospital while you explain the things you just did to Ryan.

This is an interesting case in that the patient changed right before you. It’s a great example of why capnography is a massive utility in helping us recognize patients transitioning from one status to another. Initially, you saw a patient who had thoracic trauma from handlebars vs. chest via a blunt trauma decelerating mechanism. On arrival, there were minimal complaints but significant findings.

Always appreciate the positioning of the patient and what the body is telling them to do. If you find a person awkwardly maintaining an upright position, tripoding, elevating an extremity, or removing pressure from a portion of their body, please don’t force them out of that position unless you have done a detailed assessment of the situation. It may be their body’s attempt to compensate for an underlying condition.

In this instance, Ryan wanted to stay upright, maximizing his tidal volume to allow him to take more efficient and shallow breaths because there was an underlying pneumothorax progressing. It started as a spontaneous (traumatic) pneumothorax and in your presence, it progressed to tension.

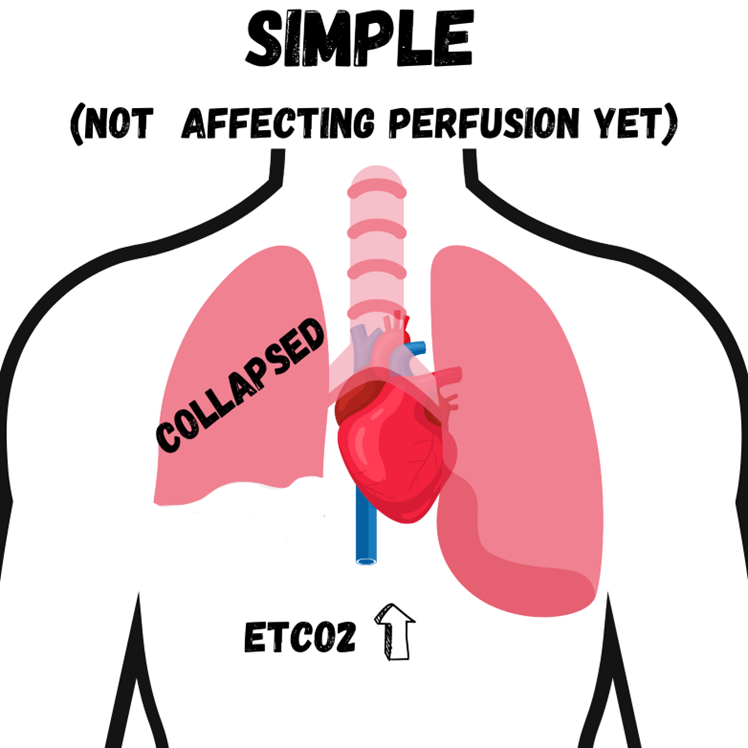

A pneumothorax alone is a ventilatory issue; one lung collapses, so the patient loses ventilatory capacity by dropping one “windbag” or “below.”

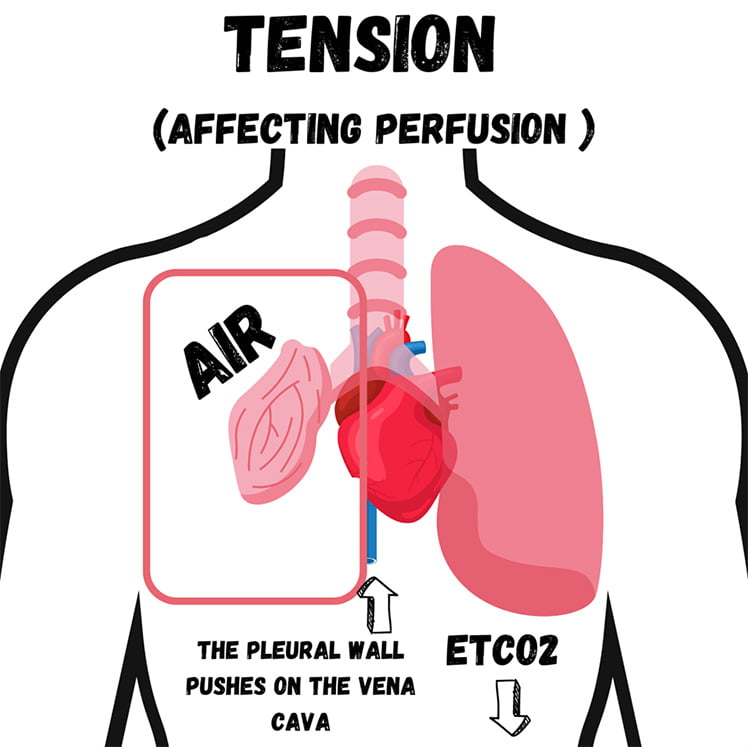

However, when that pleural space becomes so enlarged with air like a balloon, it starts to pinch or put pressure (tension) on the vena cava it becomes a problem quickly. The tension on the vena cava (the big squishy blue blood vessel that feeds the heart) is why it gets the name tension pneumothorax.

So, what is our job? Our job is to create a chimney in the chest that relieves enough air (pressure) to take that tension off the vena cava and ensure blood returns to the heart. That is our sole goal with needle decompression or finger thoracotomy. We are not re-inflating the lung. One more time, our goal in the prehospital arena is to create a chimney or relief valve so that the person’s vena cava doesn’t get pinched off and the right heart continues getting blood flow.

In this instance, Ryan transitioned from a ventilatory problem (simple pneumothorax) to a tension pneumothorax (ventilatory/perfusion problem). And as you saw, after providing needle decompression, there was a slight relief and increase in perfusion by the climbing end-tidal.

What if the needle got clogged with tissue? What would the end-tidal do?

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.