On the go? Listen to the article in the player below!

It’s a warm Friday evening in July. You’ve just wrapped up a transport and cleared the hospital. As your partner turns out of the hospital parking lot, your ambulance is dispatched to a local distribution warehouse for a worker complaining of shortness of breath. On arrival, you load your stretcher with all your gear and prepare to get some steps in while traversing the expanse of the warehouse. As you know, warehouses are never built small, and there is always a possibility that the scene awaiting you at the patient is not what you expect.

As you navigate through the maze of shelves, you find three individuals standing over top of what appears to be a middle-aged male on the floor. One is pushing on his chest; there’s a forklift next to them that the team has secured. You kneel at the man’s side on the ground and try to palpate a pulse; you find no carotid pulse. The coworker appears to be doing good-quality CPR, so you ask him to continue while you and your partner get your equipment out and in place to take over compressions and initiate ventilation. You ask, “What happened?” The warehouse workers say Larry was operating the forklift when he suddenly collapsed. He had been pulling extra overtime shifts to help pay for his daughter’s college. When he came in today he looked pale and was dragging but was stubborn and said he was going to “just get it done.” He was on the forklift for about 20 minutes when he radioed that he didn’t feel so well; he said he needed to take a break and grab some coffee.

Read: Friday Night Lights: Shift 1 – Balloons Under Water

Kevin, his friend, came over and found Larry slowly getting out of the forklift and collapsing. Kevin, who recently took a CPR class at the local YMCA, saw Larry wasn’t breathing and yelled for help while starting to push hard and fast on his chest.

Your partner takes over compressions from Kevin, and you ask him if he is OK to help with CPR if you need him. He enthusiastically agrees. The pads are on and Larry is in ventricular fibrillation and needs a shock. You charge, clear, and deliver one shock while your partner immediately gets back on the chest. You advise Kevin and your partner to switch every two minutes or five cycles of CPR. You now focus on the airway and administering medications. You position the head to align the ear with the chest wall and find what looks like a grade 3 airway. You easily maneuver the bougie and guide the tube over and through the glottis. See video below.

You inflate the pilot balloon as you say to your partner, “7.5 tube, 22mm at the lip line.” You attach in-line EtCO2 and ventilate while auscultating over the epigastrium and both sides of the chest to ensure you didn’t misplace the tube. You hear equal lung sounds while watching the EtCO2 waveform. You realize it has been two minutes since you assessed the rhythm. You have them hold compressions while you analyze the rhythm. The same chaotic ventricular fibrillation as before. You direct compressions to resume while you charge up to 200 joules. You clear the patient, deliver the shock, and CPR is started again. You know you need to get medications drawn up. You look around and ask one of the coworkers if they mind squeezing the bag-valve mask (BVM) to breathe for Larry. Tom, a skittish young man, agrees to help. You turn the VT Select BVM to the restricted flow setting.

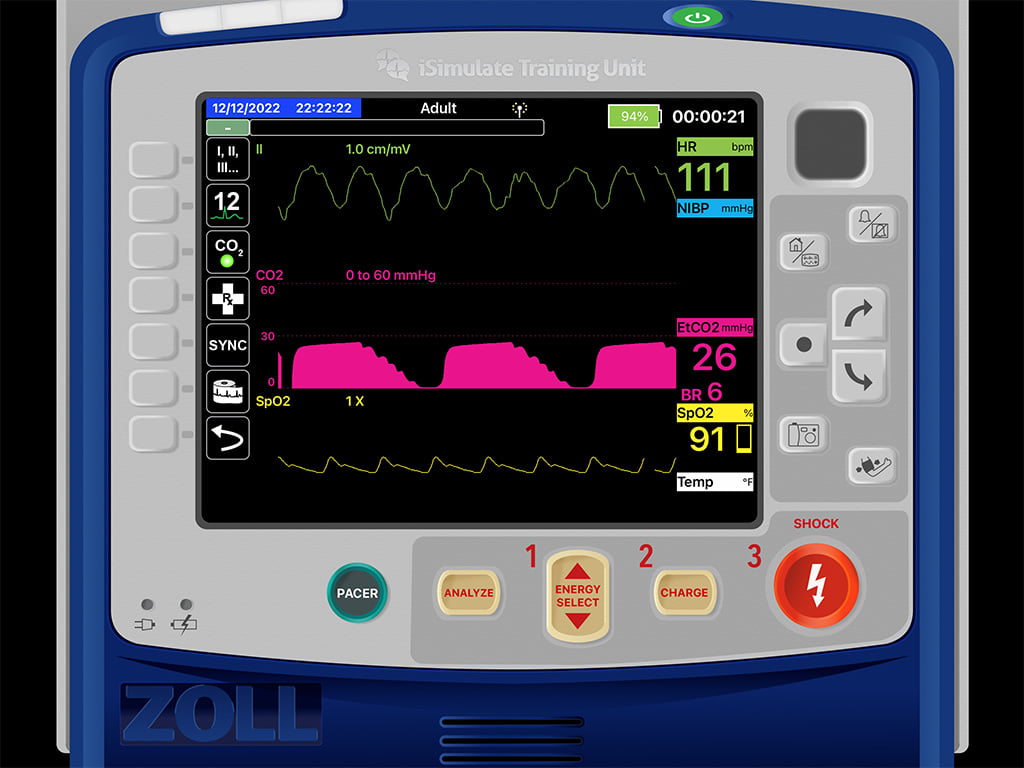

Pulmodyne VT Select BVM

You show him the technique of bagging by placing his hand under the bag so he can’t over-grasp the bag and advise him that you’ve turned the dial to help inhibit his ability to squeeze too fast. As you move to the med box, you look back and remind him, “only squeeze after the bag fills back up.” You see the a-ha moment and increasing comfort on his face as he focuses on the routine of the bag’s inflation cycle as it slowly fills back up to approximately 10 breaths per minute. You administer your first medication after cross-checking with your partner and then stand up and recap where you’re at and what your makeshift resuscitation team has done. You run down your monitor screen, finding CPR artifact on the ECG, a decent SpO2 value with a good pleth wave, and then stop at your end-tidal. Your intent was to check the effectiveness of compressions (looking for a value above 10mmHG for manual compressions) but notice the following. What do you think is wrong?

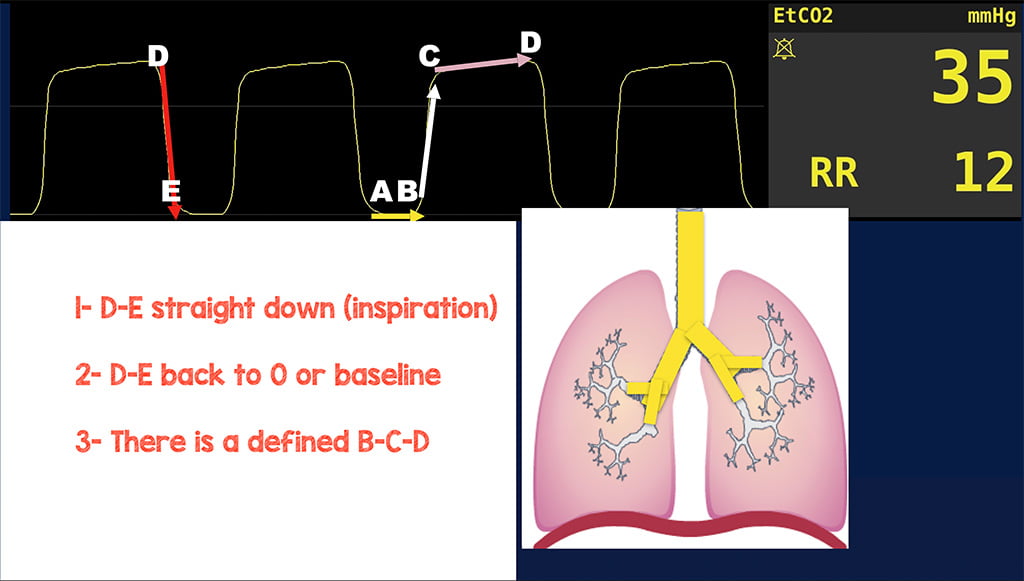

You notice the waveform returns to zero, which tells you your patient is not re-breathing, so your exhalation valve is fine. There is a defined B-C and C-D phase, so airway structures are good, and there is no broncho-constriction or alveolar problems. For some reason, the D to E phase is stepped and not straight down. D to E represents the inspiration phase on the end-tidal waveform.

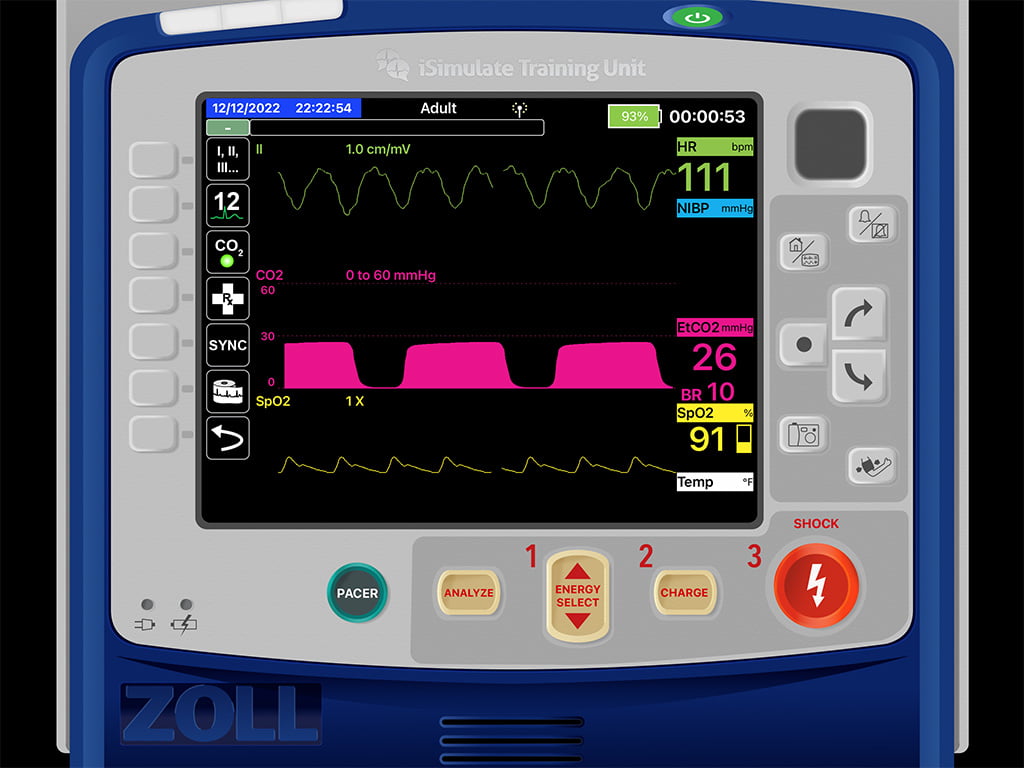

The wave should go straight down back to zero uninhibited. With inspiration, the person is inhaling ambient air; ambient air doesn’t contain readable amounts of CO2, so none should be registering on the monitor. If air is going in, not out, there shouldn’t be any CO2. So why is this D to E not straight down and back to zero? It is usually a quick fix for a person with an endotracheal tube. Likely, the cuff is not completely inflated. Thus allowing airflow around the balloon back up Murphy’s eye. You feel the pilot balloon and notice it’s very flaccid. You look over and notice the 10ml syringe used to inflate the pilot balloon on the ground still has four milliliters of air. You take the syringe, and inject that 4ml of air from the syringe into the endotracheal tube pilot balloon. You feel the pilot balloon become more rigid and notice your waveform change to the below. Are you good now?

As a recap, some of the excellent applications of using end-tidal capnography while managing a cardiac arrest patient are the management of airway and breathing (as we saw in this case), as well as monitoring perfusion status and quality of compressions. With Larry, we found a change in his D to E phase; as we discussed, this represents the inspiratory portion of respiration. Here we found that he just needed the balloon on his ET tube completely inflated to ensure adequate inhalation and ventilation of the patient.

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.