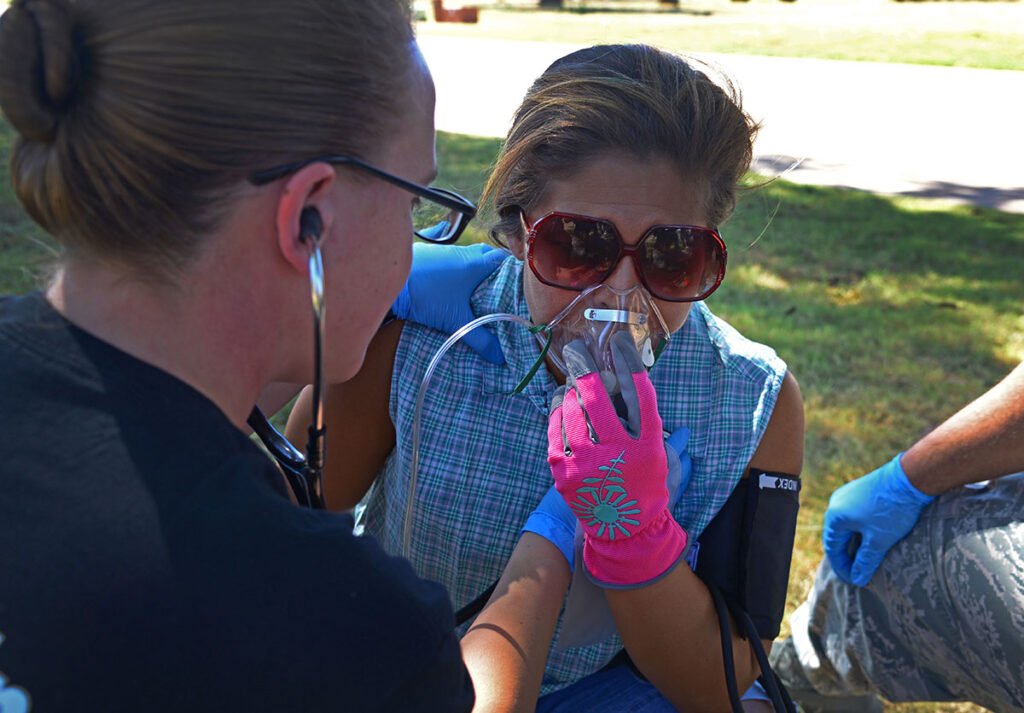

A U.S. Air Force emergency medical technician from Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., simulates taking vitals for an asthma attack victim. (Photo/Alexx Pons)

Asthma is a very common condition that causes breathing problems like coughing, wheezing and shortness of breath that challenges emergency medical and emergency medical service (EMS) providers. Asthma can be mild, moderate or severe, depending on symptoms. Asthma is a chronic illness, and although symptoms can go dormant, or even patients can go weeks or months without symptoms, patients and providers need to know their asthma action plans.1 Uncontrolled asthma, leads to preventable morbidity and increased utilization by pre-hospital care providers and health care.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes that the National Current Asthma Prevalence (2020) is 7.8% of the total population, with 5.8% (<18 years old) being children and 8.4% being adults (>18 years old).3 In 2019, the CDC reported 1,835,901 emergency department visits were asthma-related.3

Signs and Symptoms of Asthma

With an asthma episode, three physiological changes occur to provide the signs and symptoms that providers often associate with acute asthma attacks.

1) The airway becomes inflamed (red and irritated),

2) mucus increases,

3) the muscles around the airways tighten.

Asthma is diagnosed based physician evaluation to include:

1) history of asthma or related symptoms,

2) family history of asthma or relates symptoms,

3) a physical examination, and 4) medical tests.

The medical tests will include:

1) pulmonary functions test (PFT), allergy testing,

2) X-rays, and

3) lab studies.

Triggers include:

1) illnesses, e.g. common cold, flu, other illnesses,

2) activity triggers, e.g. exercise and emotional stress, and

3) environmental triggers, e.g. dust, mildew, cockroaches, weather changes, animal dander, allergens, smoke and strong odors.

Early signs of an acute asthma attack include mild symptoms that respond well to treatments. EMS providers and patients must identify the early signs of an asthma attack to include: headache; feeling tired/weak; coughing; itchy and watery eyes; drop in peek flow readings; runny and stuffy noses; sneezing; shortness of breath; increased work of breathing; and waking up at night.

As the disease process continues from mild to moderate, the provider and patient will see the following signs and symptoms: dry, repeating cough, wheezing, shortness of breath and gasping for air, chest tightness, and fatigue that prevents the patient from daily activities.

Home Care: What to Expect Prior to Assessment

At home care to treat asthma include: 1) relievers and 2) controllers. Reliever medicines help the patient once the symptoms have started. The most common at home reliever medication is albuterol from a handheld inhaler, commonly referred to as a metered dose inhaler (MDI). Used to treat acute asthma attacks, bronchospasm, bronchospastic pulmonary disease, e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, and exercised induces bronchospasm. Controllers are designed to control and fight the inflammation that occur in the airways and prevent asthma attacks from occurring. Inhaled corticosteroids, referred to as inhaled steroids, e.g. long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), Advair which combines salmeterol and Fluticasone propionate, and Singulair (montelukast). It is important to note for patients and provides that at home controllers do not relieve coughing or wheezing. Relievers are “rescue inhalers” and controllers just utilize inhaled steroids to fight inflammation.

Goals of Treatment: EMS

The goals of Asthma Treatment for EMS and the patient include:

- Maintain

- Normal activity levels

- Normal pulmonary function

- Prevent

- Chronic symptoms

- Recurrent exacerbations

- Provide

- Optimum drug therapy with minimal or no adverse effects

- Assist

- The patient in living as normal and happy of a life as possible.

- Support

- The family of the patient with asthma

- Education about the disease, its therapy, and facilitation of self-management.

The Asthma Pathway

An immediate, assessment-based asthma pathway is specifically designed to allow the provider to progress through patients that exhibit acute asthma attacks by way of chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways characterized by reoccurring symptoms, airway obstruction, bronchial hyper-responsiveness, and an underlying inflammatory process. The goal is therapeutic management, based on the pathway, looks at four distinct areas:

1) Assessment of asthma severity,

2) allergen control,

3) drug therapy, and

4) symptom management.

The asthma pathway leads to a driven treatment plan that standardizes care, improves outcomes, and are driven by EMS, nurses, respiratory therapist, and in- or out-of-the-hospital paramedics.

Classification for the pathway include four categories based on disease severity. A determination of an Asthma Score will determine treatment, from a Level 4, being most mild, to Level 1, most severe. There are many asthma Scoring techniques, but the basic of scores should be contributed to:

- Intermittent/Mild (Level 4)

- Symptoms <2 days/week

- Zero to little nighttime awakenings

- Able to speak in complete sentences

- Mild (Level 3)

- Symptoms >2 times/week but <1 time/day

- 1-4/month nighttime awakenings depending on age

- Able to speak in complete sentences, yet increased work of breathing and mild distress

- Moderate (Level 2)

- Daily symptoms

- Nighttime awakenings are >1/week but no more than 3-4/month

- Not able to complete sentences without pause or exhibiting the desire to concentrate on verbal communication. Increased work in breathing with respiratory failure not imminent

- Severe (Level 1)

- Symptoms are continual throughout the day

- Nighttime awakenings are >1/week up to nightly dependent upon age

- Cannot speak in complete sentences, moderate to severe increased work in breathing, and distress in evident in the general impression phase of the primary assessment. Respiratory Failure is imminent or occurring.

The assessment criteria needed prior to any medicine delivery is a respiratory assessment, determining as asthma score, and heart rate. This score is agency or hospital specific, but is necessary to move in the asthma pathway towards standardization of patient care. Standard patient care requirements include repeat vital signs every five minutes, maintain Sp02 > or equal to 93%.

Additional pathway scoring includes respiratory rate, auscultation (normal or decreased throughout or just the bases, end expiratory wheeze, or inspiratory wheeze), dyspnea (none to mild, moderate, or severe), retractions (none, subcoastal, intercostal, supraclavicular, suprasternal), and oxygen requirement (mild with 92 % or greater on room air, moderate 90-92 % on room air or any oxygen by nasal canula or simple face mask, or severe with <90 % on any 02 or on continuous nebulizer).

Asthma Pathway Medications

Most common pre-hospital and hospital utilized asthma medications include:

1) Bronchodilators/Reliever (Albuterol),

2) Anticholinergic Bronchodilator (Atrovent),

3) Corticosteroid (Prednisone, solumedrol), and

4) considering an advanced airway.

Bronchodilators, e.g. albuterol, Xopenex, dilates the bronchioles by relaxing smooth muscle. Administration by Metered Dose Inhaler (HFA/MDI), or Breath Actuated Nebulizer. Doses: MDI: number of puffs based on weight and severity of patient, but usually 4-8 puffs every 2-4 hours, Nebulizer: 2.5 mg albuterol in 3mL NS up to 5.0 mg albuterol in 3mL NS (2.5mg of 0.5 cc NS x 2 vials and add 2mL NS). Frequency: every 1-4 hours based on patient’s severity.

Anticholinergic Bronchodilators: e.g. Atrovent (Ipratropium Bromide). Definition: Inhibits the interaction of acetylcholine at receptor sites to cause bronchodilation. Administration: Nebulized. Doses: 0.5mg DILUTED IN 2.5 mL of saline via nebulizer. Frequency: every 20 minutes up to 3 doses or until patient improves.

Corticosteroids, e.g. Orapred, Prednisone, Solumedrol, Dexamethasone. Definition: Anti-inflammatory agent used to decrease inflammation in severe asthma exacerbation. Administration: Oral (tablet or liquid for Prednisone or Orapred). IV Methylprednisolone, e.g. Solumedrol, Doses: 1-2 mg/kg every 6-8 hours (based on patient’s weight).

Other drugs to consider for patient’s symptoms are resistant to regular treatment: Epinephrine IM for Hypersensitivity/Anaphylaxis: Dose: IM, Subcutaneous 0.01 mg/kg (0.01 mL/kg/dose of 1 mg/mL solution) not to exceed 0.3 to 0.5 mg every 5 to 15 minutes. Magnesium Sulfate IV Children and Adolescents: 25 to 75 mg/kg (maximum: 2 grams) as a single dose over 20 to 60 minutes. Note: Must be administered with a NS bolus to reduce risk of BP instability.

When to place an advanced airway or ventilate an asthmatic? According to Dr. Charles Blevins, of the nearly two million patients who visit the emergency department with asthma exacerbation, one-third (or 27,000 patients), will require mechanical ventilation.4 Based on air trapping, hyperinflation, worsening hypoxemia, worsening bronchospasm, tension pneumothorax, hypotension, and dysthymias, hyperinflation decreases venous return and thus decreased cardiac preload, and cardiac arrest can follow.4

The decision to intubate the severe asthmatic includes cyanosis, bradycardia, persistent acidosis, altered or a worsening level of consciousness, the patient exhibiting signs of exhaustion, a silent chest and respiratory arrest.4 This decision, if made, should be considered a critical airway, with the most experienced provider performing the intubation, utilizing the largest endotracheal tube (ETT) indicated for the patient, as a larger ETT with reduce airflow resistance. Induction agents and paralytics are preferred, with induction agents that have bronchodilator properties, e.g. ketamine or propofol. For paralysis, rocuronium, or any non-depolarizing agent is preferred, but if concerns of failure or the immediate need to secure a difficult airway, succinylcholine is acceptable.4

Goals of the Asthma Pathway for EMS

End goals in treating asthmatics: Oxygen saturations are 94% or greater on room air. Physical examination reveals good and increased tidal volumes with no prolongation of expiratory phase, and Albuterol is no needed to maintain oxygen saturations more frequently than every four hours. Take the time to develop an asthma pathway that progresses through the identification, assessment, scoring, treatment and education of the asthmatic. This process is beneficial for pre-hospital and hospital based EMS providers.

References

- Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters [Internet]. Norfolk (VA): Asthma in Children; [updated 2023 Feb 1; cited 2023 May 22]. Available from: https://www.chkd.org/Patients-and-Families/Health-Library/Content.aspx?contentTypeId=90&contentId=P01664

- Sawicki G. Uncontrolled Asthma in a Commercially Insured Population From 2002 to 2007: Trends, Predictors, and Costs. Journal of Asthma. 2010:574-580.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Most Recent National Asthma Data; [updated 2022 Dec 13; cited 2023 May 22]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

- Blevins C. Special Report Critical Care Medicine. Intubating Asthma. Common Sense. February 2021. Available from CCMS_CSJanFeb21.pdf (aaem.org).

Michael J. Barakey, CFO, is a 30-year fire service veteran and the chief of Suffolk (VA) Fire & Rescue. He is also a hazmat specialist; an instructor III; a nationally registered paramedic; and a neonatal/pediatric critical care paramedic for the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia. Barakey is the participating agency representative and former task force leader for the VA-TF2 urban search and rescue team and an exercise design/controller for Spec Rescue International. He has a master’s degree in public administration from Old Dominion University and graduated the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program in 2009. Barakey authored Critical Decision Making: Point-To-Point Leadership in Fire and Emergency Services through Fire Engineering Books and Videos, regularly contributes to Fire Engineering, and is an FDIC International preconference and classroom instructor.