Photo provided by the authors.

Introduction

This is a case review involving a 25-year-old male patient presenting to EMS with respiratory failure secondary to status asthmaticus. EMS was dispatched to a 911 call from an agricultural facility for a male experiencing a “severe asthma attack.”

Upon EMS arrival, bystanders were performing compression-only CPR. The patient was intubated on scene by EMS and treated in the emergency department prior to being transported by rotor-wing aeromedical transport for pulmonology and critical care not available at the sending facility.

Aggressive treatment by EMS and the emergency department allowed a rapid improvement and discharge home with no neurologic deficits.

Prehospital Assessment and Treatment

This is a 25-year-old male patient who presented to EMS with respiratory failure. Bystanders called for EMS after the patient reported difficulty breathing and appeared to be in severe distress, clutching his throat and chest while trying to use an inhaler.

When EMS arrived on the scene, bystanders were performing compression-only CPR. The patient had a strong carotid pulse and agonal respirations. Bystanders informed EMS that the patient has a history of severe asthma and collapsed to the ground approximately three minutes prior to EMS arrival.

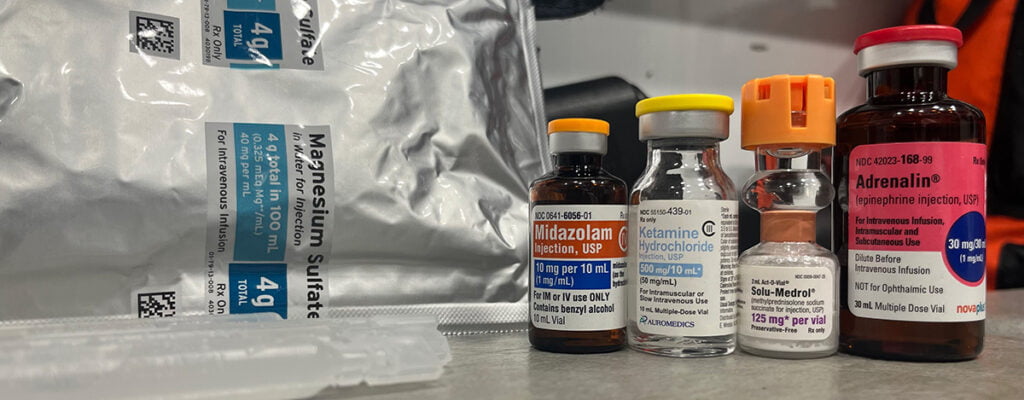

EMS administered 0.3mg Epinephrine IM and placed defibrillation pads and a LUCAS device. The patient was administered 200mg Ketamine IV and 2mg Versed IV to facilitate intubation, this prehospital service does not carry paralytics.

The patient was successfully intubated with video laryngoscopy and proved to be severely difficult to ventilate. Bilateral breath sounds were present with severe wheezing auscultated in all lung fields. Continuous waveform capnography revealed a significantly elevated ETCO2, ranging between 90-120mmHg during transport to the hospital.

Continuous nebulized treatments of Albuterol were administered, with a total of 10mg being given by EMS. Medical control was contacted and gave orders for 125mg Solu-Medrol IV as well as 2g Magnesium Sulfate IV, both of which were administered by EMS prior to arrival at the emergency department.

The patient had improvement of his oxygenation status during transport but remained hypercarbic and difficult to ventilate. The patient remained hemodynamically stable with EMS.

Background

This patient is a 25-year-old male with a history of poorly controlled asthma. He is allergic to dusts and molds and had recently begun working on a farm. His mother reported he has daily dyspnea and “asthma attack.” She also stated that he uses a Primatene Mist inhaler as he is unable to afford an Albuterol inhaler.

Asthma exacerbations are commonly encountered by EMS. According to CDC data from 2021, approximately 8% of adults in the United States have current asthma.1 These routine calls are generally of low stress to EMS providers, with common treatments being supplemental oxygen, Albuterol and Atrovent, and occasionally subcutaneous or intramuscular Epinephrine.

Status asthmaticus differs from these routine calls, being defined as “an extreme form of asthma exacerbation characterized by hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and secondary respiratory failure.”2

These patients must be treated quickly and aggressively in order to avoid morbidity and mortality associated with this presentation. Approximately 2% of hospital admissions from asthma require intubation, with intubation being associated with a 20% increase in mortality.3, 4, 5

Intubation should be performed based on clinical judgement when patients have progressed into respiratory failure, with signs and symptoms including altered mental status, hypercarbia, and exhaustion or respiratory arrest.3

Mechanical ventilation should focus on maintaining safe airway pressures (plateau pressure < 30) and allowing permissive hypercapnia during the acute phase of management.4, 5, 6 Advanced pharmacologic therapy can be used in the treatment of status asthmaticus, which will be discussed later.

Emergency Department

Upon arrival to the emergency department, the patient was adequately sedated, intubated, and hemodynamically stable. The attending physician administered 80mg of Rocuronium due to ventilator dyssynchrony, as well as initiation of a Propofol drip of 20mcg/kg/min for continued sedation.

The patient was placed on a ventilator with settings of; SIMV, Vt 470mL (approximately 6mL/kg IBW), RR 12, I:E ratio of 1:3, FiO2 1.0, PEEP 5cmH2O. Nebulized treatments of Albuterol and Atrovent were continued, giving a total of 35mg Albuterol and 1mg Atrovent during his time in the ED.

Chest X-Ray confirmed endotracheal tube placement, showed no evidence of pneumothorax or pulmonary effusion and appeared to be hyperinflated. The patient had severe respiratory acidosis as demonstrated by his arterial blood gas. ABG revealed a pH of 6.621, pCO2 >170, pO2 114.9, and HCO3 was unable to be calculated due to significantly elevated pCO2.

BMP and CBC were relatively unremarkable. Flu and COVID were both negative. Troponin was normal, D-Dimer was mildly elevated at 0.67. EKG showed normal sinus rhythm with no acute changes. The patient had a severely decreased minute volume, roughly 1.3L upon arrival to the ED, but had significant improvement with treatment.

The patient received 0.25mg Terbutaline SQ, 0.5mg Epinephrine IM, 10mg Dexamethasone IV, and an additional dose of 0.5mg Epinephrine IM while in the ED. The Propofol infusion was increased to 30mcg/kg/min where the patient remained adequately sedated and synchronous with the ventilator. The physician also attempted administration of 70/30 Heliox, however the patient quickly desaturated to 89% SPO2 and was placed back on 100% oxygen.

The patient’s ETCO2 remained elevated >100 while in the ED, however he did have improvement of his ABG as demonstrated by the second draw; pH 6.738, pCO2 >170, pO2 291.6, HCO3 was again unable to be calculated. The patient’s tidal volume also improved, with tidal volumes of approximately 400mL upon departure.

Rotor-wing aeromedical transport was contacted to transport the patient from the sending facility to a tertiary care facility for further treatment. The patient had no significant changes during flight.

Intensive Care Unit

Upon arrival to the ICU, the patient remained hemodynamically stable. His arterial blood gas showed improvement from that of the emergency department, with a pH of 7.09 and a pCO2 of 80. Paralysis was not continued as he remained synchronous with the ventilator with Propofol and Fentanyl being used for sedation.

Ventilator settings were adjusted, attempting to obtain an I:E ratio of 1:5, with his I:E ratio being 1:3 when he arrived to the ICU. Tidal volumes of 6mL/kg of IBW were used, any increase of tidal volume beyond that exceeded the safe limits of peak and plateau pressures.

His ventilatory status continued to improve, eventually reaching the target goal of an I:E ratio of 1:5. Shortly after midnight, his arterial blood gas again showed improvement with a pH of 7.38.

He was able to be extubated at 09:05 that morning and was discharged home later that evening. The patient receives follow up care with an allergy and asthma specialist.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of early and aggressive management of the status asthmaticus patient. Most EMS protocols across the country have a max dose of Albuterol at 5mg. While this dosing is generally adequate for a routine asthma exacerbation, this is not the case with status asthmaticus.

This EMS system has a max dose of 5mg for Albuterol, which was exceeded in this case. Continuous nebulized treatments of Albuterol necessitated an increased dose, with 10mg being given. Albuterol dosing greater than 5mg is safe, with 10-20mg being the standard dose for treatment of hyperkalemia.7

While in theory high dose Albuterol by EMS could lower the serum potassium, the potassium will likely be elevated due to respiratory acidosis that is associated with status asthmaticus. In the event that the patient has chronically low potassium that is further lowered by high dose albuterol, this can be replaced with IV potassium.

We recommend that further studies of high dose Albuterol by EMS and the emergency department in the status asthmaticus patient be performed. Another success of this case was the early administration of IM Epinephrine. With the patient in a peri-arrest state, Epinephrine was indicated for both its bronchodilation effects along with its vasoconstriction, inotropic, and positive chronotropic effects.4

With Epinephrine being administered three times throughout the course of treatment, it may have been reasonable to begin a continuous Epinephrine infusion of 0.01-0.05mcg/kg/min, though this is only recommended after 3 doses of intramuscular Epinephrine have been administered.5

Since this patient was showing improvement after three doses, it was decided not to begin the infusion. Ketamine was an ideal induction agent due to its bronchodilatory properties, rather than an induction agent like Etomidate that lacks this effect.4, 6

Early administration of steroids also may have had some benefit in this patient, with 125mg Solu-Medrol being given by EMS and 10mg Dexamethasone being given shortly after arrival at the emergency department. Systemic corticosteroids are recommended in intubated asthmatics, though dosing is still of debate.8

Evidence for the administration of Magnesium Sulfate is also in question, although administration of 2g as given in this case is reasonable given the minimal adverse effects.4, 5 Ventilation strategies are extremely complicated in status asthmaticus, and intubation should be considered a last resort.5

EMS providers without a portable ventilator available should use extreme caution when ventilating the intubated asthmatic, using a lower respiratory rate and being cautious of excessive tidal volumes to prevent complications such as pneumothorax. The increasing use and availability of transport ventilators could be of benefit when ventilating intubated asthmatics, preventing these complications when using appropriate ventilator settings.

We recommend that EMS systems develop protocols specifically for status asthmaticus, differentiating this from a less severe asthma exacerbation, along with training on recognition and treatment of these critically ill patients.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

- Chakraborty RK, Sangita Basnet. Status Asthmaticus [Internet]. Nih.gov. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526070/

- Stather DR, Stewart TE. Clinical review: Mechanical ventilation in severe asthma. Critical Care [Internet]. 2005;9(6):581. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1414026/

- Swaminathan A. Life-Threatening Asthma [Internet]. Core EM. 2015. Available from: https://coreem.net/core/life-threatening-asthma/

- McFarlin A, Tseng M. EM:RAP CorePendium [Internet]. Chan C, Johnson W, Mattu A, Nordt SP, Swadron S, editors. EM:RAP CorePendium. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recJcsRr7c5n59oJq/Asthma

- Brown CA, Sakles JC, Mick NW, Mosier JM, Braude DA. The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2023.

- Acute Treatment of Hyperkalemia. American Family Physician [Internet]. 2005 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Feb 14];72(9):1703–3. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2005/1101/p1703.html

- Brenner B, Corbridge T, Kazzi A. Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation of the Asthmatic Patient in Respiratory Failure. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009 Aug 1;6(4):371–9.

Cory Agler, NRP, FP-C, CCP-C, is a nationally registered paramedic and board certified flight and critical care paramedic. He works as a firefighter/paramedic in western Ohio and has experience in both 911 response and inter-facility transport. He is currently working toward a bachelor’s degree with a pre-medical track.

Craig Dues, DO, FACOEP, FACEP, is a board certified emergency physician working in rural western Ohio. He is the emergency department director at Mercer Health and president of Emergency Physicians Group, LLC. He provided prehospital care as an EMT for five years prior to attending medical school. He encourages evidenced based prehospital care and remains active in EMS education.