All images provided by the author.

On the go? Listen to the article.

After a long awaited fall, the brisk evenings are back. The change of weather can mean nothing else but chili time. You and your partner have your go to spot on the east side of town and make your way over there for a warm white chicken chili with extra spice. It’s both filling and nostalgic. You scrap the last green pepper from the side of bowl and the tones drop.

You are dispatched to a pedestrian struck approximately seven blocks away at an off the beaten path intersection. You hop in the rig look over to your partner and voice your satisfaction with tonight‘s dinner choice. They nod in agreement and also highlight the fact you both were able to finish uninterrupted.

It’s an uneventful response and you arrive on scene to find what appears to be a male lying in the roadway. There is a minivan next to the patient with the headlights shining over where they’re lying. You see the patient moving their arms and legs ever so slightly and a group of people around them trying to talk to him.

The driver of the minivan runs over to you and says he was just trying to run out and get potatoes to finish cooking dinner, when he came around the corner, the person ran out in front of him, and he never even saw him. You acknowledge with “OK, hang tight.” He keeps reiterating he stopped and saw no one.

As you walk over, you hear the patient mumbling answers to the people around him. Your partner establishes C-spine as you approach from the feet. You are concerned he is going to lift his head with all that is going on. You see bruising on his right hip and blood coming from the back of his head.

Bystanders are quick to try and gain your attention and give you “all” of the details of their findings. You listen and thank them but get right back to the patient as you have concern for his flat affect and the minimal movement he is presenting with.

You do a head-to-toe assessment and find just the bleeding behind his head and bruising on his right hip. The hip feels stable and there’s some road rash scratches on his left arm and leg.

You ask him his name and what happened, he says “Tom; I don’t know what happened.” You notice his breathing is weirdly random from quick to sigh like. You recruit a bystander to go grab the backboard so that you can log roll the patient on his back.

About the same time the field supervisor arrives along with the fire department, you get Tom packaged up and in the back of the unit so that he isn’t lying on the cold asphalt anymore. You continue your assessment, establish an IV, and one of the firefighters who you continue to hear them call “Rook” helps connect the patient to the monitor for you.

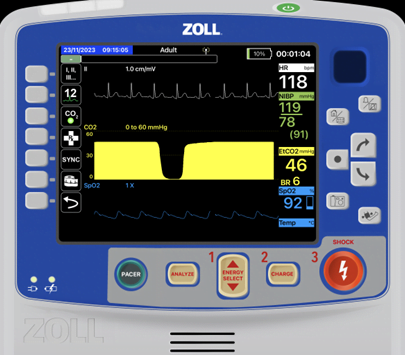

By now, Tom has stopped talking and he’s not answering your questions. You notice the following vital signs on the monitor and look to your partner.

You both give each other the glance of “take the airway.” Your partner starts to draw up the medication‘s while you explain the procedure and what you need from “Rook.” You get your camera set up and your tubes out along with your bougie and place the scalpel and 6.0 tube (finger/Bougie/cric) and iGel 4 on the patient’s chest for your back ups (always have a plan B and C). Your partner pushes the ketamine, and then the rocuronium.

You ask “Rook” to turn on the suction and you place it next to the patient’s head. You scissor the lips, introduce the blade and approach the airway with the bougie. You’re ecstatic to find no blood and very limited secretions.

You are able to quickly pass the 7.5mm tube through the cords and call out “22 at the lip line.”

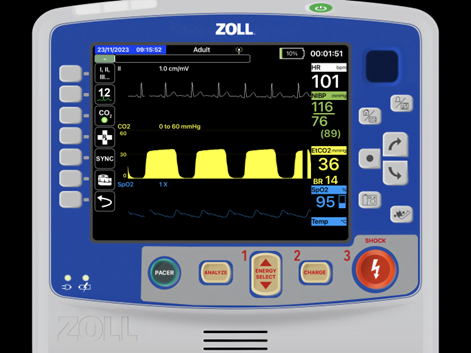

You secure the ET tube and hook up capnography while auscultating lung sounds and find the following vital signs on the monitor.

You confirm and are confident with the placement and pass the “bag of life” over to “Rook.” You then coach him on the rate and volume you need to deliver.

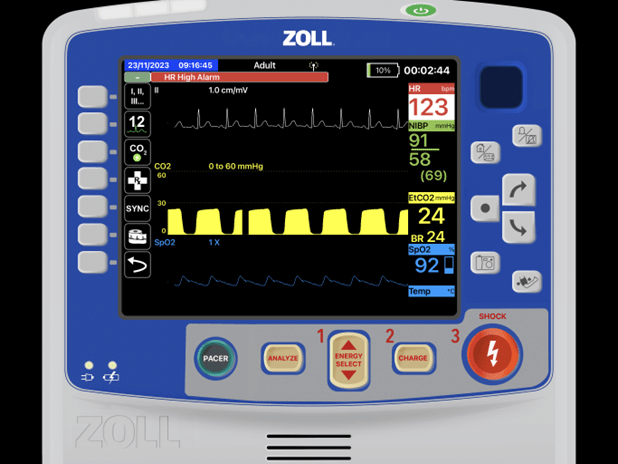

You grab the phone and sit down to call report into university. Sarah picks up the phone for report and you start rattling your trauma alert sequence. When you get to vitals the monitor grabs your eye. What happened?

It could be a bunch of things:

Is sedation wearing off? In this instance this isn’t the issue as the C-D phase of the capnograph waveform is flat, not dipped like below.

Is it internal bleeding? Could be with the increasing heart rate and tanking EtCO2 and BP.

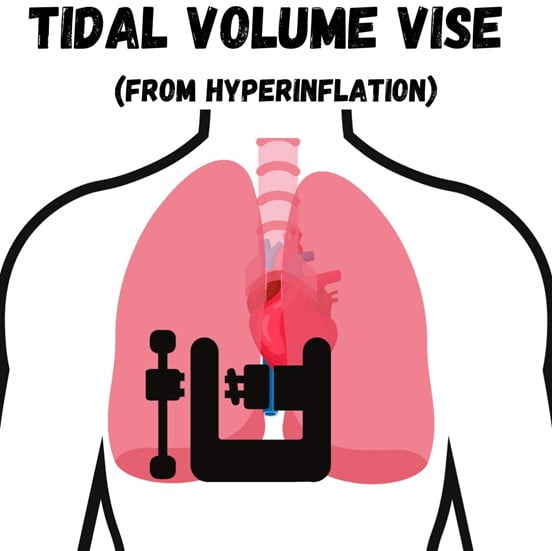

But with an intubated patient receiving manual ventilations your eyes should go right to the “squeezer.” You see “Rook” using two hands and squeezing every ounce out of the BVM into the patient. In this situation, “Rook” has been over squeezing the bag increasing the thoracic volume thus putting pressure (tension) on the vena cava.

What you’re seeing is the body compensating for the reduced preload from vena cava compression.

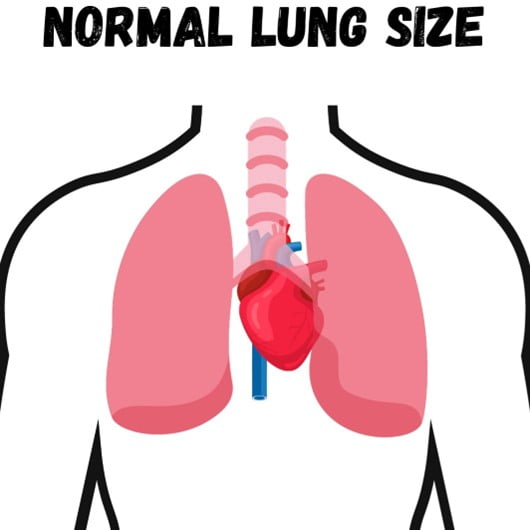

It is commonly mistaken that too much thoracic volume “squeezes” or “pushes” on the heart and aorta making the perfusion reduce. It is actually the soft squishy blood vessel (vena cava) that is the vulnerable one. Remember venous return banks on the negative pressure generated with breathing and body movement to get blood back into the thorax.

You ask him to put his one hand under the bag and squeeze only with his thumb and middle finger. (When you grasp the bag over the top the tendency is to completely clench what you are grasping with good dexterity and strength. This is why it is easy to control a motorcycle throttle).

He gives you a weird look but plays along and quickly looks down at his hand and his lack of ability to over squeeze.

You get back to your alert report with your 11min ETA notation to the receiving facility and ask if there are any questions.

After you transfer care and are outside with the crew, you revisit the basics of BVM management including the under grip two finger squeeze (next time you are bagging a patient give it a try) and debrief the call.

There are devices now on the market with rate and volume reduction control like the VT Select. It has a mode to reduce BVM refill to approximately 10 breaths a minute and tidal volume of 500-600 due to it being 1200ml as opposed to 1500-1700ml.

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.