When was the last time you treated a child in respiratory distress? What do you remember? Did you feel comfortable managing the case? Did you feel confident in your care plan? What resources did you have available to you? Did you feel ready to escalate your care if needed? Did the patient get any better? Are you sure? Do any of these questions even matter? Are you sure? What did you do to help the patient? What did you do to help the parents? Did you do anything to help yourself after the call?

Are you sure?

Our most difficult patient encounters often leave us with more questions than answers about the patients and ourselves. Now, add complications and insecurities associated with pediatrics, and you are living a common theme and fear amongst prehospital providers. Add respiratory distress and the high risk for asphyxia and cardiac arrest1 and that insecurity may expand exponentially. You probably know, or have at least heard of the catchphrase of “bag brady first” which is a good start to keep a pediatric out of cardiac arrest, but have you ever found yourself asking: “Okay, now what?”

The anatomical and physiological differences of pediatric patients are a good place to start this journey and both are especially important when treating respiratory distress. Let’s work from the outside starting at the all-important head of the patient. Consider how big and disproportionate a pediatric patient’s head is compared to the rest of their body. While a big head (comparatively) means a much smaller chance of intellectual delays and other unfortunate conditions,2 it can lead to serious issues when trying to manage an airway. Working further in, remember pediatric patients have large tongues and less control of them, while they are typically nose breathers, this large tongue size also tends to get in the way of airway control by either the patient or providers.

Images/Glen Keating

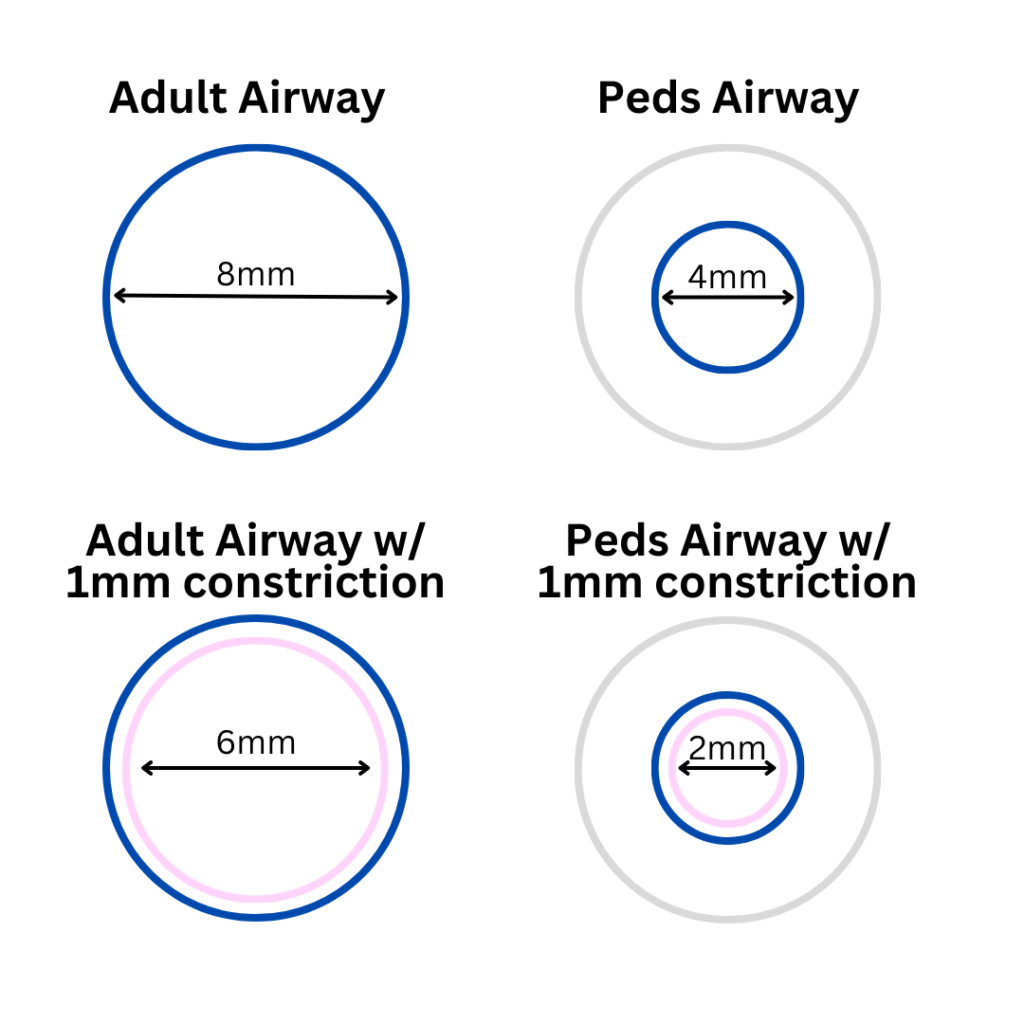

Finally, consider the traffic nightmares, which are bottlenecks, and remember that kids have the same thing around the area of the larynx, cricoid and thyroid cartilages as the upper airway funnels down into the lower airway.3 In the process of resolving respiratory distress in pediatrics, be aware of positioning to optimize the unique features of the pediatric airway. These factors need to be an early consideration when developing an effective care plan, and appropriate patient positioning is some of the best low-hanging fruit that prehospital providers can take advantage of for pediatric respiratory distress. While easy to resolve, positioning is not often the only reason a patient is in respiratory distress so your assessment is invaluable when considering treatment of other problems caused by upper airway issues.

The etiology of upper airway illnesses may be inflammatory in nature like when the patient is suffering from things like croup, epiglottitis or abscesses (both peritonsillar and retropharyngeal). While croup is the most common of that list4 it is important to be mindful of the others and even of things like foreign bodies when forming a differential in the field.

Continuing our journey of pediatric respiratory anatomy leads us to the trachea, main-stem bronchi, bronchioles and the capillary covered alveoli. As a whole, pediatric lungs are smaller, but most often they are healthier than their adult counterparts having not been exposed to as many toxins and chemicals over several decades of life. It’s for this reason that pediatric lower airway distress is either a result of asthma, bronchiolitis, or pneumonia.

That’s it!

We all probably know asthma is where airway smooth muscle constricts while inflammation further reduces the patient’s ability to ventilate. Often, this is triggered by some sort of insult to the lungs and the patient usually has a known history of asthma. With advances in long-acting inhaled steroids, many adults and pediatrics go long stretches without needing rescue medications and can be managed through routine primary care medicine appointments rather than emergency department visits. Patients having breakthrough asthma attacks that warrant 911 activations, should be considered serious and it should be assumed that other rescue medications have been ineffective. Some of the patient’s home medications for this may include albuterol and Atrovent (via inhalers and/or a nebulizer) for fast relief as well as inhaled or oral steroids for maintenance.

Bronchiolitis is another common cause of pediatric lower airway disease and if you dig a little deeper you’ll find a variety of causes, one being respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV has come to prominence amid recent surges in case numbers during a brutal winter in the United States. When considering bronchiolitis, knowing the past medical history of the child is important. Important history that should be noted includes patients less than three-months old, history of prematurity, lung and heart disease and immunodeficiency as these can all worsen the effects of RSV and associated bronchiolitis. Unlike an asthma exacerbation, the onset and progression of bronchiolitis is often much longer, and symptoms usually peak at five-to-seven days.5

Last but not least is pneumonia. Most often, pneumonia is bacterial but can be viral, both with similar effects to the patient starting with difficulty breathing. With it being an infection, the patient may have fever and chills accompanied by a productive cough often with thick, discolored sputum. With airway constriction and gas exchange interference due to these secretions, pneumonia presents an especially serious concern for our pediatric patients with smaller airways and alveoli. Even in developed countries, pneumonia in kids poses a significant risk of morbidity and mortality6 and EMS providers should maintain vigilance for deterioration when patients present with pneumonia and similar symptoms.

With a better understanding of these ideas, give yourself some time to breathe, consider the source of the problem as you walk into the house to see your patient. Take the time to do a good assessment and build an understanding of how and why the child is presenting as you see them. A good, comprehensive assessment is the cornerstone to this management so start with the basics:

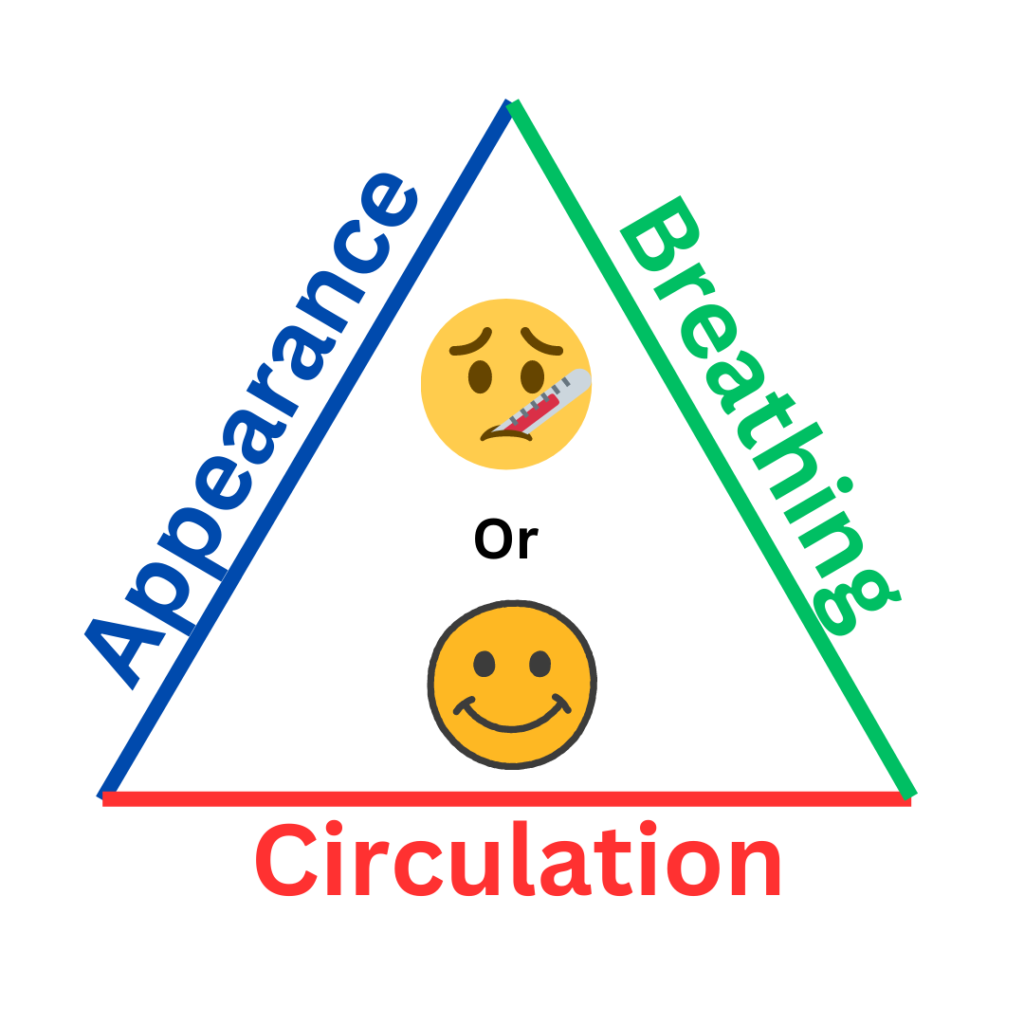

- Our initial survey via the Pediatric Assessment Triangle, or PAT, focuses on the largest concern for pediatric patients – appearance, work of breathing and circulatory status.7 Appearance and work of breathing likely deserve special priority in respiratory distress cases. The PAT is a fantastic infographic diagram which helps guide us in our assessment upon initial contact and has been proven, across many disciplines (especially EMS), to be highly predictive of children who are objectively sick or not sick.8 The goal with the PAT is to match observable, objective findings to sick children so life-saving interventions can be started sooner and we can all breathe a little easier.

Adapted From: Dieckmann, RA et al. The pediatric assessment triangle: a novel approach for the rapid evaluation of children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010 Apr;26(4):312-5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181d6db37. PMID: 20386420.

- Measuring vital sign values and comparing them to age-appropriate standards is another important early assessment step. Normal blood pressure readings in pediatrics can vary and can be skewed by inappropriately sized equipment (cuff) so a quick reference sheet, a pediatric specific smartphone app or chart in your pediatric equipment, can be very helpful. Remember other vital signs like ETCO2 are useful as their values are the same across all ages and can be early predictors of shock and decompensation.9

Adapted from: ADEWALE, L. (2009), Anatomy and assessment of the pediatric airway. Pediatric Anesthesia, 19: 1-8 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03012.x

- Visual inspection of the respiratory patient especially from the waist up. When evaluating the severity of distress, look for see-saw breathing, intercostal and subcostal retractions and jugular vein distention just to name a few.

- Frequent auscultation of lung sounds is so important that it necessitates its own bullet point. Don’t be surprised if you hear wheezes on inspiration and expiration, indicating significant constriction. Remember, you are dealing with smaller airways – 1 mm of constriction can be impactful to adults and it poses an even larger issue to pediatrics, increasing resistance when measuring both laminar and turbulent flow.2 Listening with a stethoscope is always necessary to appreciate the severity of wheezes and stridor even when audible in the open. Use auscultation via stethoscope to assess for trends in the patient’s condition and the effectiveness of interventions.

When considering what interventions are necessary, how aggressive the treatment should be, whether the benefits of the interventions outweigh the risks, and whether there are alternatives, fall back on what you appreciate in your assessment and the trends that are presenting with the patient. Early identification is key to effective management, given that pediatrics compensate longer but have a smaller overall reserve and crash faster. Get eyes on your patient early, keep eyes on your patient, and watch for changes (hopefully improvements) in the patient’s presentation. More on all of this in the next article.

It is essential to discuss what is happening with these patients, physiologically during their respiratory emergency. As we close out this first segment, it is equally important to discuss why these scenarios may stick in our minds, especially with how much the figurative spotlight is shining on provider wellness right now. One reason may be that it’s not often that EMS even encounters pediatric patients, and current research puts that number anywhere from 5-13% of all EMS encounters.10,11 Additional research shows that when EMS transports a pediatric patient, they tend to have higher Severity Classification Scores than patients who present to the emergency department via other modes.12 Consider that the simplest interventions are usually the most frequently done and thus are the least risky and are associated with high rates of provider competency, familiarity and confidence. On the other side, the interventions which are indicated for these sick kids are the riskiest. They are infrequently done in the field, and are associated low rates of provider success, competency, familiarity and confidence.13 It’s no wonder that there is extra emotional stress associated with treating pediatric patients. If you have ever felt added sympathy for the patients, notice yourself relating to them and your own children, relating to the parents – sometimes needing to treat them as additional patients, then you’re not alone. These are all common themes reported by EMS providers when asked what emotional factors make pediatric patient encounters difficult.14,15

Just as pediatrics have smaller reserves, we’re finding certain experiences quickly drain the “brain battery” of EMS providers as well. Some providers may cringe at the thought of treating a pediatric patient regardless of the nature, as a result of bad experiences in the past. It is important to remember that there are good options at an EMS provider’s disposal to help improve the patient’s respiratory condition, but providers may also have to make some incredibly tough decisions. These decisions come with potential long-term implications for the patient, their parents, and the providers. While this pressure is likely appreciated by everyone, that doesn’t make the effects any smaller. This pressure underscores the need for investments (education) in EMS provider patient care and decision-making skills, and equipment to make quality care and good outcomes a reality.

What if I told you that the tools exist to give your pediatric respiratory patients a better chance for success and a faster turnaround back to their normal lives? Something fairly simple that works relatively quick and that you have probably used before on adults for similar complaints. I’m talking about applying CPAP to our pediatric respiratory distress cases. In part two of this article, we’re going to walk through how and why CPAP works for kids, and some pearls for use. Part 2 will also cover what you need to set it up successfully within your system and confirm it’s being safely and effectively deployed for pediatric respiratory emergencies.

References

1. A.A. Topjian, T.T. Raymond, D. Atkins, M. Chan, J.P. Duff, B.L. Joyner Jr., et al.Part 4: pediatric basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care Circulation., 142 (2020), pp. S469-S523

2. Harris S.R. Measuring head circumference: Update on infant microcephaly. Can. Fam. Physici. 2015;61:680–684.d

3. ADEWALE, L. (2009), Anatomy and assessment of the pediatric airway. Pediatric Anesthesia, 19: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03012.x

4. Balfour-Lynn IM, Wright M. Acute Infections That Produce Upper Airway Obstruction. Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. 2019:406–419.e3. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-44887-1.00023-7. Epub 2018 Mar 13. PMCID: PMC7152287.

5. Shawn L. Ralston, Allan S. Lieberthal, H. Cody Meissner, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Bronchiolitis. PediatricsNovember 2014; 134 (5): e1474–e1502. 10.1542/peds.2014-2742

6. Madhi, Shabir A. MD, PhD et al. The Burden of Childhood Pneumonia in the Developed World: A Review of the Literature. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 32(3):p e119-e127, March 2013. | DOI: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182784b26

7. Dieckmann RA, Brownstein D, Gausche-Hill M. The pediatric assessment triangle: a novel approach for the rapid evaluation of children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010 Apr;26(4):312-5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181d6db37. PMID: 20386420.

8. Horeczko T, Enriquez B, McGrath NE, Gausche-Hill M, Lewis RJ. The Pediatric Assessment Triangle: accuracy of its application by nurses in the triage of children. J Emerg Nurs. 2013 Mar;39(2):182-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2011.12.020. Epub 2012 Jul 24. PMID: 22831826; PMCID: PMC4318552.

9 Cully M, Treut M, Thompson AD, DePiero AD. Exhaled end-tidal carbon dioxide as a predictor of lactate and pediatric sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Dec;38(12):2620-2624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.075. Epub 2020 Aug 1. PMID: 33046322.

10. Nemsis national data report, 2021: https://nemsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/NEMSIS-End-of-Year-Report-2021.pdf

11. Shah Shah MN, Cushman JT, Davis CO, Bazarian JJ, Auinger P, Friedman B. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by children: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008 Jul-Sep;12(3):269-76. doi: 10.1080/10903120802100167. PMID: 18584491; PMCID: PMC5237581.

MN, Cushman JT, Davis CO, Bazarian JJ, Auinger P, Friedman B. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by children: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008 Jul-Sep;12(3):269-76. doi: 10.1080/10903120802100167. PMID: 18584491; PMCID: PMC5237581.

12. Dayal P, Horeczko T, Wraa C, Karsteadt L, Chapman W, Bruhnke L, Litman R, Ruttan T, Kuppermann N, Marcin J. Emergency Medical Services Utilization by Children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Dec;35(12):846-851. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001143. PMID: 28398935.

13. John Lyng, Matthew Harris, Maria Mandt, Brian Moore, Toni Gross, Marianne Gausche-Hill & J. Joelle Donofrio-Odmann(2022)Prehospital Pediatric Respiratory Distress and Airway Management Training and Education: An NAEMSP Position Statement and Resource Document, Prehospital Emergency Care, 26:sup1, 102-110, DOI: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1992551

14. Guise J, Hansen M, O’Brien K, et al Emergency medical services responders’ perceptions of the effect of stress and anxiety on patient safety in the out-of-hospital emergency care of children: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014057. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014057

15. Jessica N. Jeruzal, Lori L. Boland, Monica S. Frazer, Jonathan W. Kamrud, Russell N. Myers, Charles J. Lick & Andrew C. Stevens (2019) Emergency Medical Services Provider Perspectives on Pediatric Calls: A Qualitative Study, Prehospital Emergency Care, 23:4, 501-509, DOI: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1551450

Glen Keating is an airway enthusiast from Columbus, Ohio. Glen is paramedic in charge of quality improvement for a suburban EMS system north of Columbus and spent 11 years as a respiratory therapist at a Level-One trauma center in Columbus. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in emergency medical care from Eastern Kentucky University and is an Ohio EMS Instructor with a special focus on airway and ventilation management. He is the owner of PreHospital Elements, LLC., an EMS education and quality improvement firm based in Ohio.