Images provided by the author.

On the go? Listen to the podcast below!

The other day I was working an arrest and I watched the provider preparing to intubate take a big deep breath and hold it while they used their fingers to scissor open the patient’s lips and then introduce the blade into the mouth. They had not elevated the head to optimize the airway angles and ease the need for vallecula displacement. They just went right in, holding their breath, and immediately started to struggle and shake. I tapped them on the shoulder and said, “Hey, let’s bag the patient, reposition the head, and try again.”

They were really starting to shake by this point. They backed out and started to bag the patient. Another provider rolled a towel under the head to align the ear with the chest. I asked, “Are you good to go?” They shook their head yes. Right before they stopped bagging, I said don’t hold your breath; take a deep breath in, hold it, and then let it out slowly. They gave a bewildered look but tried it.

They attempted again and were able to place the bougie and guide the tube over very quickly. After the call I asked them why they originally took a deep breath and held it. They replied, “Oh, that’s what my instructor taught us, so you complete the task in the time it would take in between breaths. Like if the patient was breathing, you do it in between the breath you gave with the BVM and the next one you give once your procedure is done.”

This logic is flawed in so many ways. It is well-intentioned but physiologically out in left field. Let’s take a second and review how the body responds to apnea and hypoxia.

High PaCO2 triggers a stress response in an effort to drive change. The body becomes tachycardic and tachypneic. With that increased respiratory rate comes an ever-increasing recruitment of costal muscles to help enhance the depth of breath as the need for CO2 ventilation increases. It is the chemoreceptors in the carotid bodies and aortic arch that send their litmus paper (like) assessment of the CO2 concentration to the medulla and then calls the pons on the brainstem to please have the diaphragm increases its rate and depth to get rid of this CO2.

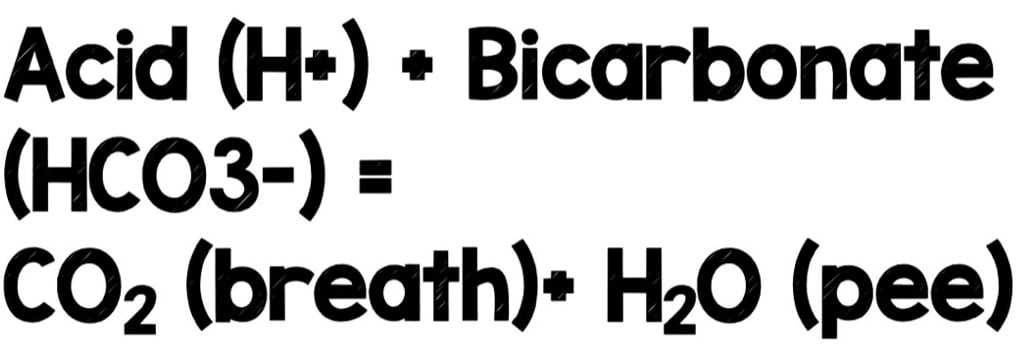

The is seen regularly in short, self-resolving bursts daily. A good example is when you stand up from sitting for a long period of time. When you do this, you recruit more muscle groups, increasing cellular metabolism and generating more CO2 (the hydrogen ions at the end of the Krebs cycle + the bicarbonate that your kidneys have free-floating in the blood that makes CO2 and water).

That increase in CO2 is cleared by a slight spike in your respiratory rate purges the CO2 from your body. Try it, and you will see the magic of what we discussed in action.

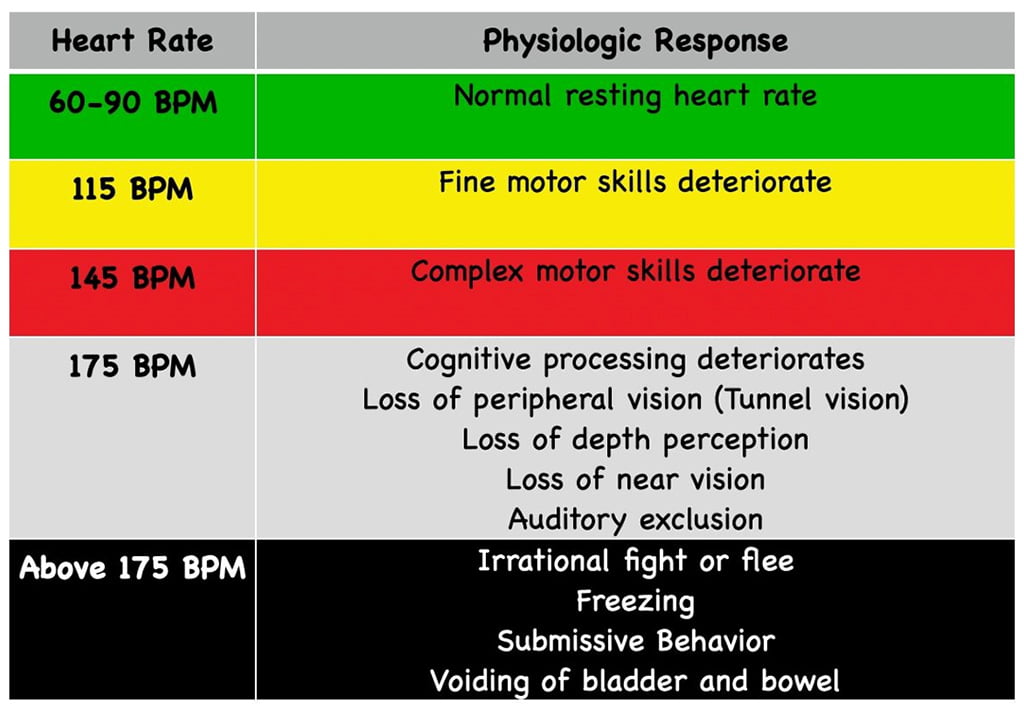

Back to our topic at hand. When the body finds itself in this position where it ramps up, it isn’t helping solve the CO2 problem. It gets worse. The heart rate continues to climb, and the body starts to shut down areas that aren’t critical. This includes the front of the brain responsible for decision-making and reasoning.

Intubating a patient or conducting a high-risk procedure isn’t part of our autonomic function pathways. So the logic center that controls our ability to conduct the steps to complete said procedure starts to turn off. As our heart rate continues to climb, more and more of our cognitive capacity decreases, and we dive deeper into our fight, flight, fear state.

We can also get into a loop that is hard to break as our body becomes hyper-focused on fixing the issue. This compounding effect is all the reason to not hold your breath before doing procedures or making decisions.

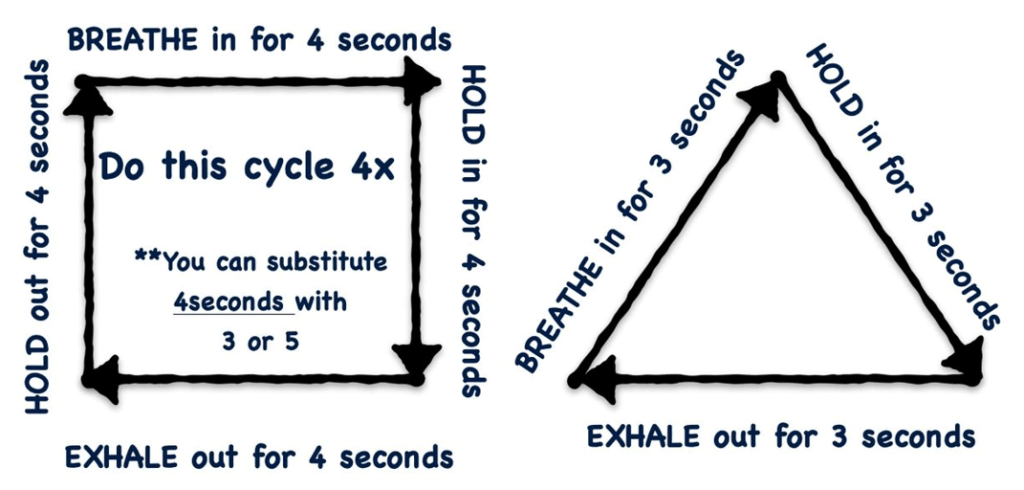

There are techniques we can use (triggering our parasympathetic nervous system) to put us in a calm, clear state before conducting a task. The two most common are box breathing and triangle (delta) breathing.

Each option triggers the parasympathetic system to kick in and helps lower the heart rate and catecholamine dump. Many high-performing professionals use this technique before making critical decisions or pulling the trigger. We need to practice this more in public safety. We can start by using this when going on the call; this way, our on-scene reports, initial findings, assessments, etc., start with a clear open mind. The worst thing that could happen is the provider arrives with their heart rates in the 170s, and they arrive with tunnel vision.

Let’s get back to our initial case of provider self-induced hypercapnia and tachycardia. Holding their breath is one of the worst actions to set oneself up for failure that could have been done. It not only doesn’t make logical sense but creates a physiologic stress loop that becomes unrecognizable by the person in it, thus making it hard to break out of it.

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.