All images created by the author.

Here we go again, another Friday night springtime with a cold snap kicking in. As you grab your job shirt from your locker, look over your partner and tell them you’ll meet them in the rig. You hop in the passenger seat and adjust the position of the chair so it’s perfect, or at least as perfect as a beat-up ambulance will get.

You start organizing the cab to your liking, and you hear the CAD chirp about the same time your partner opens the door, hops in, looks over to you, and asks where we are headed. You’re headed to the local community center for a 70-year-old male with an allergic reaction and shortness of breath.

You make your way over to the center which takes about three minutes, pull up, and put the rig into park only to be greeted by approximately 10 overly excited individuals trying to draw your attention to the front door.

You gather your bag of tricks and box of life (Lifepak) and make your way inside the front door, and you find Earl sitting upright in a chair with his arms on the table and a plate of food in front of him, breathing fast and struggling to breathe. You and your partner make your way to him, introduce yourself, and he says hi… I’m… Earl.

Your partner starts to hook the patient up as you grab your stethoscope out, and you look to the bystander, who appears to be of a similar age with her hand on his shoulder, and ask what happened.

She tells you, “He’s my husband. Earl hadn’t been feeling the best all day and was going to stay home, but he didn’t want to disappoint her for tonight’s fundraiser dinner. He got about halfway through his meal and said he couldn’t breathe.”

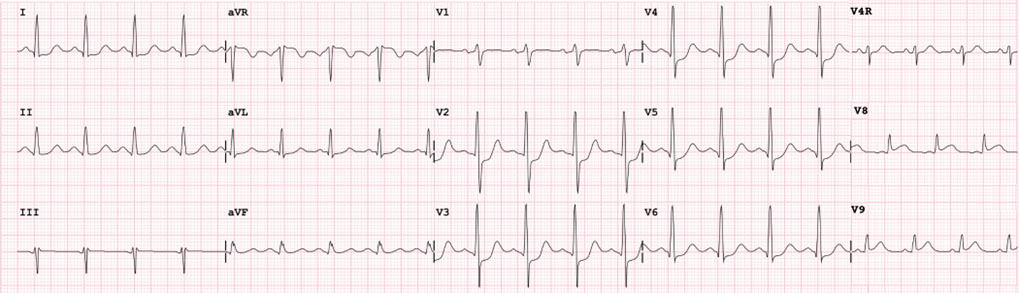

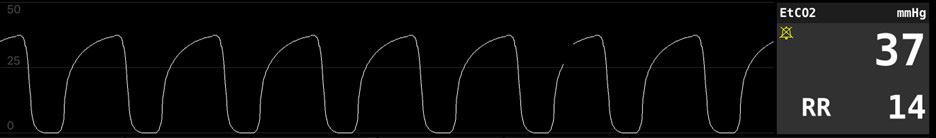

You glance over the plate to find a half-eaten steak with brown sauce on top of three shrimp tails and a cob of corn next to it that hasn’t been touched. Your partner has Earl hooked up and points to the monitor at about the same time you’re lifting his shirt to listen to lung sounds. The monitor shows the following, and you can hear the following:

Scan the QR code to hear the lung sounds.

What are your differentials based on patient presentation, onset, and lung sounds?

What did the other vital signs tell you and help you with in stratifying your differentials?

Your partner points to the capnography waveform and then to the diastolic blood pressure. You shake your head yes and say in a low tone; I heard wheezes. Your partner again points to the capnography waveform and the diastolic, looks up to you, and says, “Cardiac?”

You look back to the patient’s spouse and ask if Earl has any medical problems, takes any medicine, or has any medical allergies. She says he has a history of three stents, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type two diabetes, and is allergic to sulfa.

You then ask if he’s had any recent changes in weight over 10 pounds, more or less from his last medication change, and she shakes her head no! Your partner starts to pull out the CPAP and almost presents it as a yes or no to you, and you agree with the nod of the head.

You ask Earl to open his mouth. You look in the back of his throat, see nothing, and look around the ring of his collar and the upper portion of his chest as you put chest leads on for a 15-lead.

You find no hives after you’ve got all the electrodes on. You go down to his ankles to see them slightly swollen and pitting. You turn back to the spouse while you hear your partner coaching Earl to hold the CPAP and try to take good breaths, encouraging him to hold it himself and do his best to tolerate it, and he promises.

He won’t put the strap on until Earl gets him the thumbs up. You asked the spouse if there’s anything else she can think of that would’ve caused this or if he’s had anything like this in the past.

She says he doesn’t have any allergies but sulfa, and he’s never had an allergic reaction to shrimp or steak. You thank her for the information, but let her know you think this is a heart problem, not an allergic reaction. You also ask her if he got sweaty like this all of a sudden or if he has been sweaty throughout the day, and she says it came on all of a sudden. You take a look at the 15-lead and find the following.

You pass the 15-lead over to your partner, and they quickly run their eyes across it. They look up at you and say “aspirin,” as you agree. You transmit the EKG, then let Earl know you’re going to put some bigger electrodes on to get a bigger picture of the heart, and he seems so preoccupied with the CPAP and focusing on breathing that he nods his head, “OK.”

Your partner hands you the aspirin to give Earl as he event stamps it on the monitor. You then grab the defib pads out and place them under Earl’s shirt. You grab another look at Earl after the CPAP (notice the rise in end tidal from the PEEP working?).

Afterward, you work the cot over towards Earl so that he has to do little to no movement, and you lift him onto the cot, keeping him upright for his breathing mechanics and ease. You let the spouse know you’ll be taking him to university, and you ask if he has a cardiologist he sees regularly. She lets you know he sees Dr. Brittany Smith at Uptown Cardiology Associates. In the back of the unit, you start your two IVs on the left arm (in case Earl is a candidate for radial artery access), and you call in your STEMI alert to university.

So, what is going on with Earl? Why the wheeze?

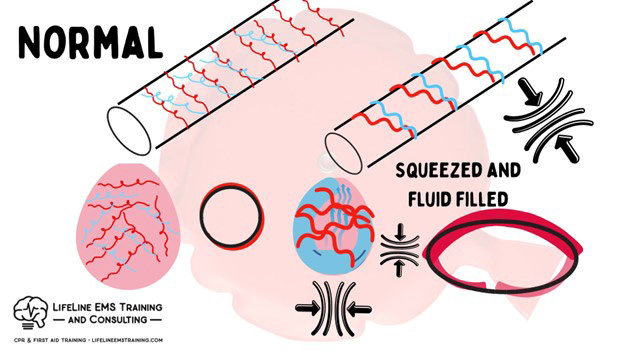

A couple of things cause the wheeze in this case, all resulting from left ventricular backup and its impact on the pulmonary vasculature, and the pressure increase, causing the edema.

It’s a whistle more from the fluid, creating a narrowing as the ventilated gas leaves the alveolus and moves up the bronchial. However, that bronchial and alveolus are wrapped in that same pulmonary capillary bed that is backed up and engorged due to the left ventricle being reduced in output.

So, imagine not only the alveoli filling with fluid but that same alveoli and bronchiole being externally bear-hugged by swollen vessels (think varicose veins).

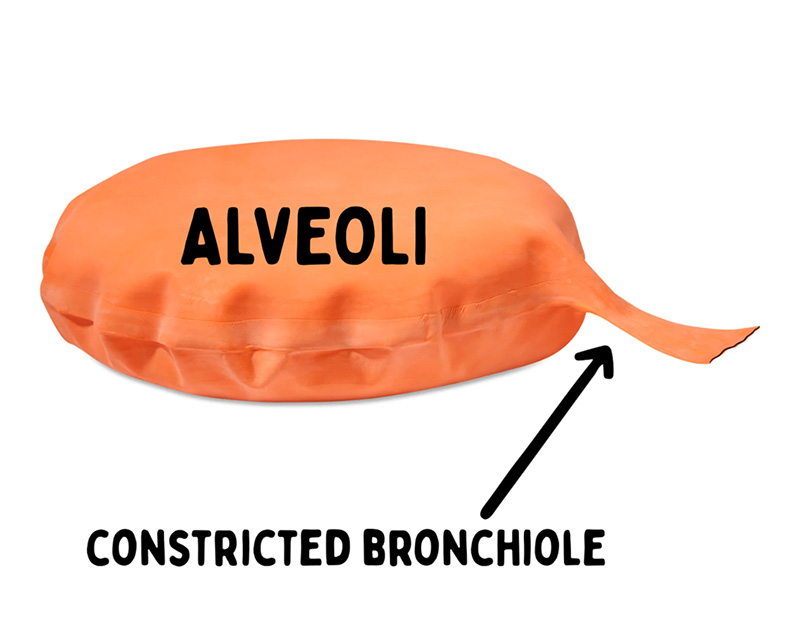

So they’re hugged by swollen vessels (bear hugs) and contain liquid that moves with the respiratory cycle. That bear hug and liquid make a “whistle” more than a “wheeze” in that it isn’t as defined as asthma’s three-part attack (smooth muscle construction (outside the tubes), wall inflammation (the tubes), and lung butter (mucus/inside the tubes) creating a drastic difference in stratification of the airway thus the extreme variation in tube (bronchial) size and CO2 concentration.

This is also why you get the C-D phase rounding on the end tidal wave like we have discussed in previous shifts.

Asthma is more whoopee cushion-like; the tubes are also the problem, and there is still a good full alveolus on the back end

Cardiac is a both problem.

BronchoSPASM—gets the med bundle to help relieve the SPASM (muscle constriction) triggered by the inflammatory response, which = swelling (histamine release, immune factor response) and lung butter (we always say to help correlate the sticky fly paper effect to grab pathogens in the airway so the cilia can walk the lung butter up and out) from mast cells in the lungs.

The end-tidal wave is the sum of all airways ventilating. So, if you have shark fins, you have “total” bronchoSPASM throughout the lungs. A large-scale problem gets large-scale treatment.

Wheeze is a whistle. You can have localized infection (pneumonia in 1, maybe two lobes or less), which incites a localized immune response to a localized area. But the sum of airways isn’t affected. So, you give reduced treatment if needed.

You want lung butter in pneumonia to grab the pathogen and get it out. So consider holding off on the Atrovent. You want them “expectorating” or bringing up the butter. So, albuterol with added saline helps open the local spot but keeps airways moist and butter flowing.

Pneumonia won’t have a wave change unless it’s bad enough over a very large area (total left lung, etc.), and even then, it will likely be subtle but a change nonetheless.

Nebs are used to open airways.

When airways constrict, their ventilation is the first thing impacted. Inhalation is an active process, and ventilation (exhalation) is passive. Hence I:E time being 1:2-1:3 at normal. So when the ventilatory ability is a problem, the end-tidal rises due to the reduction in ventilation (in the presence of a good depth of breath), then pulmonary it is.

When the waveform is unchanged, and the end-tidal value drops with a normal depth of breath, think of a perfusion problem (sepsis, cardiogenic, volume, etc.)

Earl is a prime example of using good history taking, a detailed assessment, and all of your physiologic data to help find a treatment path that is correct and best for your patient.

I will leave you with this. What if you were blinded by dispatch bias and focused only on what the bystanders thought was wrong, driving you to treat Earl for anaphylaxis, giving him epinephrine, diphenhydramine, DuoNeb and steroids?

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.

Such a great breakdown and explanation. Wheezing in CHF patients with no sharkfin confuses most people of why that is. Chris’ information here easily explains the pathophysiology of it. Will be using this article to better educate paramedics I work with!

The more I know, the more I find I don’t know…;)