Images provided by the author.

It’s T minus 37 minutes until the end of the shift. It’s not often that you can catch nine calls in 12 hours, all of which were transports. As you look over to your partner to ask what they’re doing this weekend, the CAD chirps. You read it aloud, “Lift Assist 7878 Hill Road for a 78-year young male who needs help off the floor.” You adjust your seat back up and hit en route.

It’s about a three-minute ride over where you pull up to a single-family home with a light on in the top right window. You grab your gloves and head up to the door, where you’re greeted by Suzie, the spouse. She states “he” was trying to get back in bed from the bathroom and fell down. He insisted on her not calling, but he cannot get up. You ask where he is and what his name is, and she gestures upstairs and tells you his name is Travis. You make your way upstairs and find Travis lying next to his bed at the doorway to the bathroom.

He’s lying flat on the ground and doesn’t appear to be in pain or guarding anything. You walk over, kneel next to him, and introduce yourself; while shaking his hand, you feel his skin is cool and slightly clammy. You ask Travis “how did you end up down here”? He states he went to the bathroom and fell on his way back to bed. He adamantly insists he needs help back into bed. As you do a quick head-to-toe, you try to make small talk to buy time while you assess the situation; something doesn’t feel right.

Travis looks at you and asks again, “Can you just get me back into bed, please!” You catch his very matter-of-fact tone that has a hint of embarrassment. You advise him you’ll gladly do so; you have to get a couple more things, and you look up to your partner and mouth monitor to them. You continue to ask Travis questions and try to get a feel for how he is feeling, why he is on the ground, and why his skin feels so cool. He is continually adamant about just getting him back into bed.

You ask him if he got lightheaded or felt dizzy before he ended up on the ground. He says, “NO!” Your partner returns with the monitor, and you let Travis know you’ll gladly get him back into bed, but you have to get a couple of his vital signs and ask his permission to get him hooked up. He reluctantly agrees.

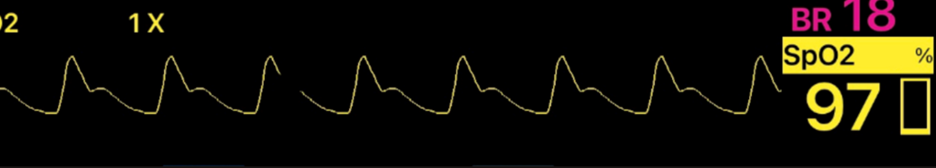

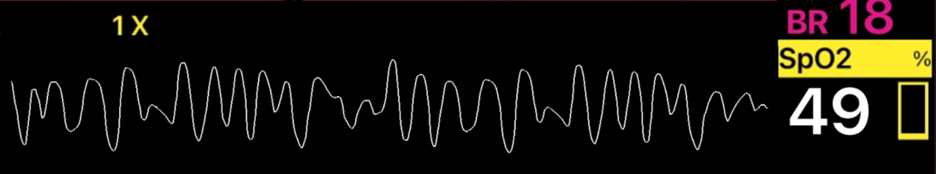

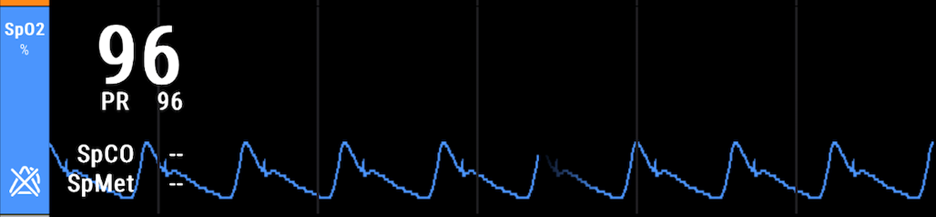

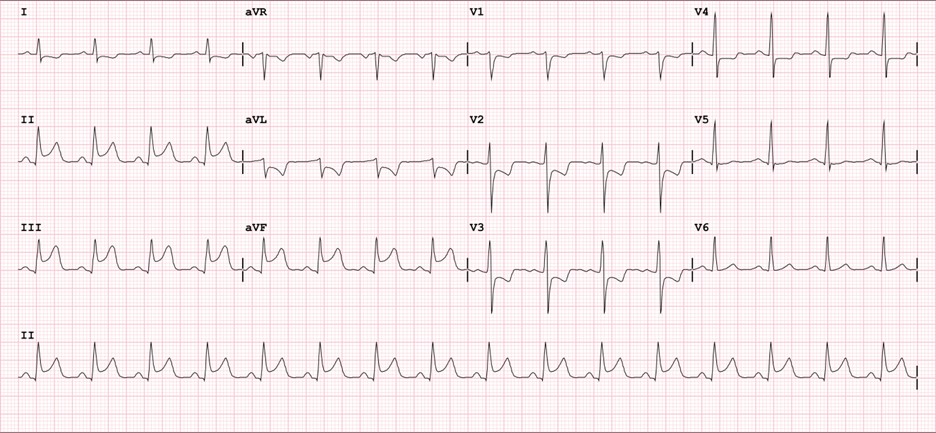

You help get him hooked up, look over at the monitor, and you find the following. What are your thoughts?

There are a couple of things here that you should be worried about right off the bat. First is the elevated heart rate, and yes, I challenge you to start to retrain your brain to make heart rates in the 90s of otherwise resting patients elevated. Check your pulse next time you’re lying on the couch watching TV.

I guarantee it’s not in the 90s; something is happening, and it’s not just Travis being upset. The next concern is the pulse ox pleth wave. The pulse ox is a good discerner of perfusion quality based on the waveform amplitude. Never trust the number if you don’t have a good, consistent wave. Note the difference. The one that looks like Vfib isn’t accurate. The signal isn’t consistent or quality.

You see Travis’s pleth is low, meaning poor or shunted perfusion. Now this isn’t just from shock it can be from hypothermia as well or medications like Levophed.

(***Street Trick***) After putting on a tourniquet for hemorrhage control, when transporting, you can put a pulse ox on that extremity. If you get a waveform, you haven’t stopped blood flow.

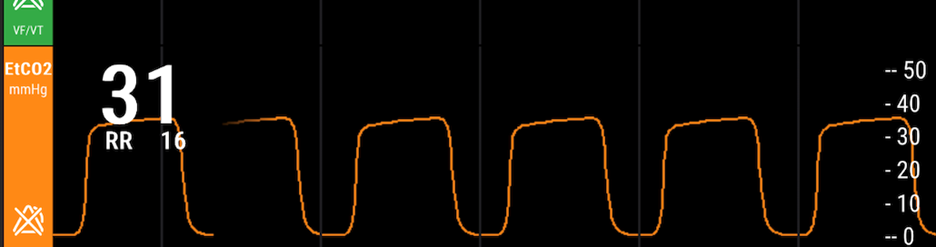

The last is the capnography. You noticed the elevated respiratory rate and the low value.

This should be another alert! We have talked in previous articles about how venous blood flow back to the heart relies heavily on the negative pressure of breathing to draw it back up and in. When a person is tachypneic, one thing that should always cross your mind is, is this a perfusion or shock issue?

In this instance, Travis is flat on the floor after losing his balance and trying to dismiss the fact that something could be wrong. After appreciating these values, you gesture to your partner to peek at the monitor. You ask Travis if it’s OK if you can do an EKG and stroke assessment. He tells you, “Fine, but then put me back into bed.” As your partner places the stickers on for the EKG, you conduct a quick Cincinnati with all three being negative. Your partner grabs the EKG.

You ask Travis how long he’s been feeling bad; he looks you right in the eye, puzzled with a “how did you know that look.” You see him back off and tell you, “Since last night.” You immediately follow with some things are going on with your heart that we need to take you up and get checked. He looks at you with a defeated look and says, “OK.”

You let him know you’re going to need to give him some aspirin and two IVs. Your partner explains the situation to Suzie on his way out to grab the Reeves stretcher. You let him know you need to put two big electrodes on him so you can get a better circumferential picture of his heart (PS- those are the pads in case he tries to code on you, and that is a good way to not bring light to the fact you’re putting pads on to shock him if his heart stops).

This is an example of how using capnography, SpO2, and HR can help guide you down a path of “something isn’t right.” Understanding changes to vital signs in situations that don’t make sense needs to be investigated further. Lastly, lift assists aren’t just “falls.” If you haven’t dug a little more into why lack of friction, function, or gravity took the patient off their normal path, you are wrong!

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.