All images created by the author.

It was another shift on the streets, but with it being the holiday season, any opportunity for overtime is a win.

That includes the day side shift. You’re fortunate to know the staffing officer who sends out some of the most creative and compelling staffing pages. You got hooked on the daily staffing text, with a creative sales pitch about wanting to work.

It’s been a minute since you worked the day side, but it’s the weekend, so everything should settle out just nicely, and still no management on duty. Your partner is an old friend you haven’t worked with for close to five years, but like any good partner, within five minutes of starting the shift, it’s as if you’ve never stopped working together.

You decide to go down to the local coffee shop and grab your iced black eye to start the day. As you both walk out the door with your fresh beverage, you can hear the CAD chirp from 30 feet away.

Your radio starts to go off, requesting your services at a local bank about 2 miles away. You’re getting called for a 62-year-young female experiencing an allergic reaction.

It’s only about two turns from where you’re at. You hit en route, start on your way, and about 30 seconds down the road, you get a supplement saying the patient’s tongue is swelling and throat is closing, and there is no EpiPen available.

An older gentleman in a suit greets you and frantically waves you inside. You grab your bag of tricks and box of life and head in with your partner. You’re escorted to the back, where there’s a boardroom, and clearly a meeting has been going on for a while.

You find three people huddled around your patient, who’s sitting upright in a chair, and she visually fixes on and follows you and your partner as you make your way over to her.

AI image created by the author.

Leticia was in the middle of her meeting when her friend noticed she was biting her tongue with her upper teeth. You find Leticia sitting upright with a clearly swollen, protruding tongue, but no discernible hives anywhere you can see.

You grab your stethoscope while your partner hooks her up to the monitor, and you ask if it’s OK if you can listen to her lung sounds. She acknowledges by shaking her head yes. You’re caught off guard by her calmness when the three coworkers are clearly distraught.

Really, all that you see out of the ordinary is the swollen tongue, you listen to lung sounds, and she has great air movement in all four fields, as well as listen to the side of her neck, and you hear unrestricted airflow.

Your partner stands from a crouching position, points to the monitor, then turns to the coworkers, trying to gain a history of events prior to you being called to help Leticia.

Does anything jump out at you? Based on the presentation and the vitals, what are your primary concerns?

You ask Leticia if she can swallow easily, and she puts her hands up in a so-so manner. You ask her if she’s itchy, and she shakes her head no. You ask her if she is having any trouble breathing, and she gives you the so-so gesture.

You ask her if she has any known allergies, and she shakes her head no. You ask her if she’s been prescribed an EpiPen before, and she shakes her head “not again.” You then ask her if it is okay if you look around the collar of her shirt, on her belly, and on her back to see if she has any hives. She nods OK.

You look back at the monitor and are really struggling to put two and three together. You were dispatched for an allergic reaction and have only a swollen tongue as a symptom, similar to anaphylaxis, but lack any hives or wheezing.

You heard from the coworkers that they haven’t had anything to eat yet today because the breakfast order was delayed. You ask Leticia whether this came on suddenly or has been happening over time, and she points to her watch.

You try to clarify by asking, “Has this been going on for minutes, hours, or days?” She shows you two fingers, and you ask, “Option two: hours?” And she shakes her head yes.

She seems reluctant and self-protecting on her end to want to answer verbally, but is clearly not in distress, just a lack of comfort. You ask if this has ever happened before, and she shakes her head no.

You ask if she takes any medications, and she says shakes her head yes. You ask if they’re in her purse, and she again shakes her head yes. You ask if it’s OK to take a peek at those medications, and she gives you a thumbs-up.

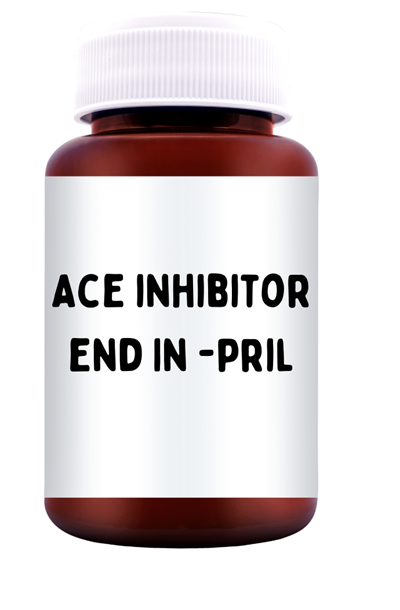

You find a statin, a medication for her gout, and a blood pressure medication. You ask if these are the only three, and she shakes her head yes. You note that all of them were filled two weeks ago, and you ask again whether any of these are new doses or just new prescriptions.

She gestures number two with her fingers. You ask if she’s taken all of these prior or if two weeks ago was the start of any of these, and she gestures again the number two. While you look over to your partner puzzled you notice Letitia starts taking her thumb and index finger on her right hand and massaging the lateral sides of her throat.

You look over and ask her if it’s becoming itchy and she shakes her head no, she gestures with her fist into her left hand and you try to clarify by asking do you feel pressure and she shakes your head yes.

You tell your partner let’s get her loaded up and in the back of the unit you’ll do an EKG and an IV and you ask her if that’s OK and she gives you a thumbs up. as you’re explaining how you want Leticia to sit over onto the cot as you help her up, your partner looks at you and asks.

Do you think this is caused by her blood pressure medication? It takes you a second to process but you remember that there’s a small percentage of patients taking ace inhibitors that can experience angioedema.

You look back at Leticia asking her while holding the blood pressure medication up to her, have you been taking this a while and she says yes. You ask if it’s been months or years and she shows the number two on her finger then the number three on her finger and you ask, have you been taking this for three years and she shakes her head yes.

You ask again if she has any trouble swallowing and she shakes her head no. And your eyes migrate back to your capnography.

You note a great wave form with good ventilation and oxygenation via the pulse ox. You let her know that all of her vitals look OK and that you’re going to take her up to have her tongue and airway assessed and that you’re not sure what the cause is.

It might be her blood pressure medication and she looks at you puzzled. You get her loaded up in the back of the unit and start towards University. While calling in she taps you on the leg while her other hand is again massaging the lateral part of her throat.

You ask if the pressure is getting worse and she gestures “so so” with her hand, you let her know it’s going to be OK and you’re only about four minutes away from the hospital and she shakes her head with a OK.

So, what do you think is happening to Leticia?

Leticia was at a early morning board meeting that was far from stressless. had been taking an ACE inhibitor for her chronic hypertension for several years without experiencing any noticeable side effects, so when she began feeling a peculiar fullness in her mouth during a staff meeting, she initially assumed it was stress from her presentation.

Within minutes her words became thick and difficult to articulate, and colleagues noticed her tongue enlarging with each passing moment. Although Leticia believed stress was the primary cause, the real issue was the slow but dangerous development of ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema.

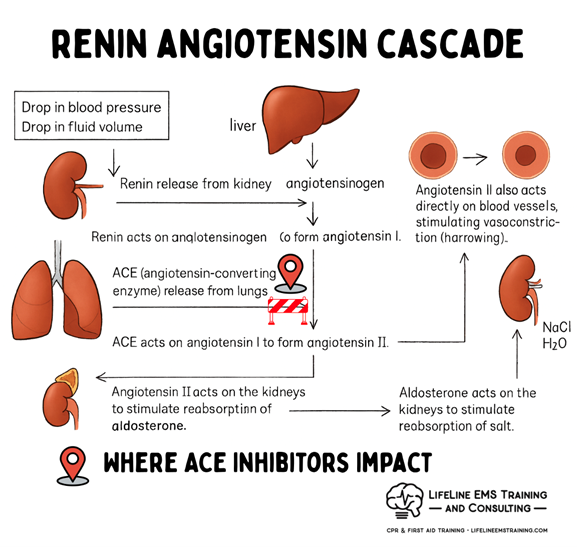

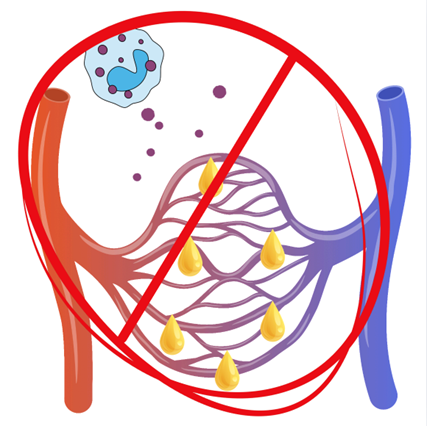

ACE inhibitors, such as lisinopril and enalapril, function by blocking angiotensin converting enzyme, which lowers blood pressure by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin cascade. This same enzyme is responsible for breaking down a molecule called bradykinin.

When ACE is inhibited, bradykinin accumulates in the body. Elevated bradykinin increases vascular permeability, allowing fluid to shift out of blood vessels and into surrounding tissues. Areas with loose connective tissue, such as the lips, face, and particularly the tongue, become especially susceptible to swelling.

In Leticia’s case, this resulted in a rapid expansion of the tongue that interfered with both speech and airway patency.

One of the unusual features of ACE-inhibitor angioedema is that it can appear suddenly, even after years of stable, uneventful use. This delayed onset is thought to be related to subtle accumulations of bradykinin over time, patient-specific genetic factors, shifts in enzyme activity, or gradual physiologic changes due to aging or comorbid conditions.

As a result, tolerance in the past offers no guarantee of protection in the future. For Leticia, years of normal use did not prevent the sudden emergence of a potentially life-threatening reaction.

Stress also played a significant role in worsening her condition. Emotional and physiological stress increases the release of inflammatory mediators, which can amplify bradykinin’s effects and accelerate the swelling process.

Stress leads to rapid, shallow breathing and increased oral dryness, further irritating the tissues of the mouth and throat. In addition, the muscle tension that accompanies stress narrows the airway, making any tongue enlargement feel more pronounced and more dangerous.

Leticia’s anxiety about presenting likely intensified the sensation of airway compromise and may have contributed to the swelling’s progression.

The tongue is particularly vulnerable in this condition because it contains a dense network of blood vessels and abundant loose submucosal tissue that easily absorbs fluid. Without the rigid structure found in other parts of the body, the tongue can expand dramatically in a short period of time.

This swelling quickly leads to difficulty speaking, swallowing, or managing secretions, and can progress to airway obstruction. In Leticia’s situation, her coworkers noticed her muffled voice before she fully realized that her airway was at risk.

Clinically, ACE-inhibitor angioedema is particularly dangerous because it is not mediated by histamine release.

This means that medications typically used for allergic reactions, such as epinephrine, antihistamines (Benadryl), and steroids, often offer little or no improvement.

The priority is airway management, especially when red flags such as tongue swelling, drooling, stridor, difficulty breathing, or rapid progression are present. One thing to note is that because the presentation is similar to anaphylaxis, it isn’t uncommon for do-gooders to try to help or administer anaphylaxis medications like EpiPens or antihistamines to the patient.

This is always good to find out as these medications cause an increase in upregulation and stress response to the body, especially with adrenaline.

Note with Leticia again, she didn’t have systemic allergic reaction signs like hives or bronchoconstriction (wheezes) and her End Tidal showed a good normal waveform.

Another important consideration is that bradykinin-mediated angioedema often progresses even after the patient reaches medical care. The window of greatest risk is typically the first two to six hours.

Patients like Leticia require close monitoring in a setting where advanced airway management, including intubation or even surgical intervention, can be performed without delay. So, your transport decision should include facilities with in-house anesthesia.

Leticia’s experience highlights the importance of recognizing ACE-inhibitor angioedema as a unique and potentially fatal adverse reaction. It emphasizes the need for EMS providers, clinicians, and even workplace responders to understand that tongue swelling in a patient taking an ACE inhibitor should be viewed as an airway emergency rather than a typical allergic reaction.

Her case demonstrates the complex interplay among bradykinin accumulation, stress-related physiologic changes, and the tongue’s anatomical vulnerability, underscoring the importance of rapid assessment and airway-centered management.

This case also underscores the need to avoid dispatch bias and always to conduct a thorough assessment.

More from the Author

Friday Night Lights: Shift 17 – A Change in Dinner Plans

Friday Night Lights: Shift 16 – Smoky Nights

Friday Night Lights: Shift 15 – Squeaky Peaked Exits

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.