All images created by the author.

This time of year has to be your least favorite—when the daytime is warm enough for a T-shirt and shorts, but the evenings are cold and brisk, warranting a jacket and jeans.

Four calls into the shift, and it’s already 11 p.m. You roll out of the emergency department doors with your partner, joking about food choices for dinner and how picking something that’s good and hot *or* cold is the best decision on a Friday night.

You climb into the rig to find your now cold pizza still sitting there, waiting for you in the box. You mark yourself “available” on the CAD and finish the last slice while eyeballing the grease that’s started to congeal from the cold temperature—the cheese now hardened and the pepperoni curled up in defeat.

But at the end of the day, calories are calories, and being full and happy, riding into the night with your partner, is all that matters.

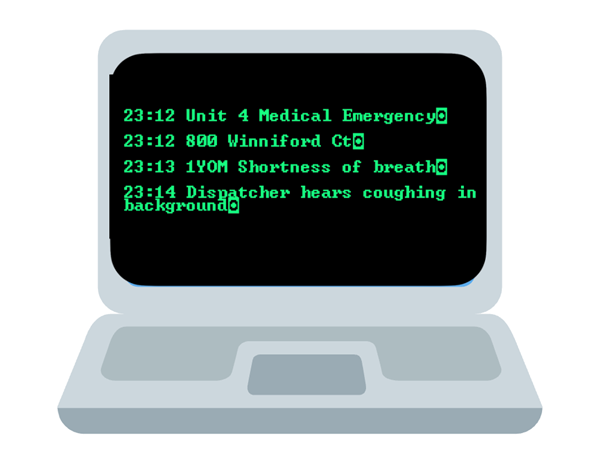

Your partner puts the vehicle in drive and starts to head out of the hospital grounds when the CAD chirps: You’re being dispatched to a residential address for a one-year-old with trouble breathing.

You mark “en route” and start playing human GPS, giving turn-by-turn directions. You’re only about two miles away. With the cold weather, the streets are quiet, with little traffic and fewer people. You make it there quickly and uneventfully.

Upon arrival, you find a frantic parent waving at you like you’re a 747 pulling into the airport gate. You grab your bag of tricks and box of life, and head up to the door.

Inside, mom is rocking a little boy, holding him upright in a chair. She’s clearly concerned, looking back and forth between him and you. The boy—Elijah James—is sitting upright with red, rosy cheeks, pale lips and a patented one-year-old onesie decorated with police cars.

You greet Mom and use the onesie as an icebreaker:

“We really gotta work on your onesie selection. This would look so much better with ambulances on it.”

She grins and chuckles, then tells you, “He’s just not acting right or breathing well.”

You look her in the eye and reassure her:

“We got you.”

Your partner kneels down beside her while you ask what’s been going on and when it started. Mom explains that Elijah became fussy earlier today, didn’t eat his evening breastmilk, and has been acting strange, breathing fast and shallow.

You hear your partner to the side, working calmly to establish rapport with Elijah through soothing communication. Elijah gives a distant stare—passive, tired, blinking intermittently. You note that, through the onesie, he appears to be using accessory muscles to breathe—a pattern resembling seesaw breathing.

You ask mom if he was full-term, had any complications, medical conditions or medication allergies. She denies all of the above—he was full-term, has no allergies, and hasn’t needed medications before.

She says no when asked if anyone else in the home has been sick. You ask who watches Elijah during the day, and she replies that grandma and papa have watched him the last two days since she returned to work. You clarify if they’ve been sick at all—again, she says no.

A brief scan around the room reveals the typical “toddler-proofed” home, with an extra 10% effort to ensure nothing is within Elijah’s reach. You ask about urine output and bowel movements. Dad responds that Elijah only had one wet diaper today.

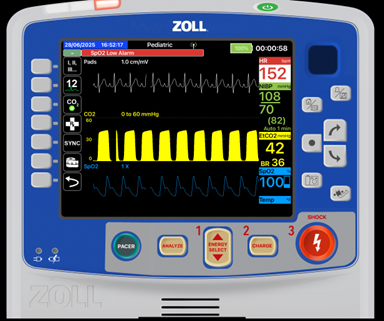

Your partner has gathered vital signs by now. Elijah was completely cooperative and non-reluctant during the assessment. Your partner also exposed Elijah’s chest and confirmed the seesaw breathing.

You ask mom whether the upright position Elijah is in was her doing or if it’s how he prefers to be. She says, “This is how he wants to sit. Any other way, and he gets fussy.”

You check for drooling or wetness at the collar of his onesie—none found.

What are your differentials based on the history, assessment and vitals?

You pull out your trusty stethoscope and auscultate Elijah’s anterior chest, letting Mom know you’ll need her help to sit him forward so you can listen to the back. You hear some mild upper airway noise bilaterally (listen with the QR Code below), but the bases are clear.

You migrate to the lateral neck, knowing that in children, upper airway sounds can resonate through the thorax, presenting as lung sounds. On auscultation of the neck, you hear the following sounds.

What are your updated differentials now?

You inform mom about your findings and gently ask if there’s any chance Elijah put something in his mouth. She is adamant that he hasn’t.

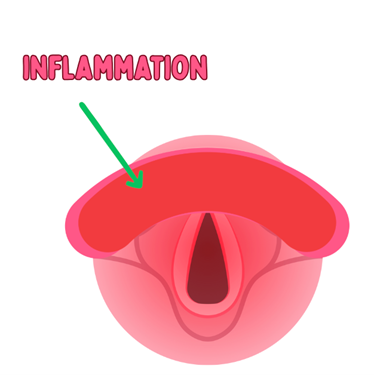

Using your flashlight, you peek into his throat without disturbing him too much. You observe redness and inflammation.

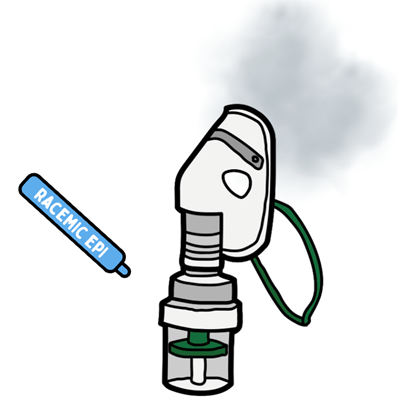

You explain to mom that this likely appears to be an upper respiratory infection and offer to take Elijah to University Hospital just down the street for further evaluation and medication. She agrees, visibly relieved. You offer to start him on a nebulized epinephrine treatment, which will begin reducing inflammation.

You remind her to grab essentials—phone, wallet, shoes—while you begin treatment. Dad says he’ll follow in the car. Once all are ready, you walk mom and Elijah, who’s tolerating the nebulizer well, to the unit. You secure him in your pediatric restraint system, offer him a beanbag animal for comfort and recycle your vitals.

Once in the rig and settled, you coach mom on holding the nebulizer mask just in front of Elijah’s face so that he doesn’t panic by having a mask on his face, but still gets the medicine to breathe in. Then, you make your call to the hospital.

So, what is going on with Elijah?

It appears Elijah is suffering from croup, a viral upper respiratory infection affecting the larynx and upper trachea. His symptoms had a gradual onset, starting with fussiness, decreased intake, fatigue and mild respiratory distress. This progressive presentation makes a foreign body obstruction less likely.

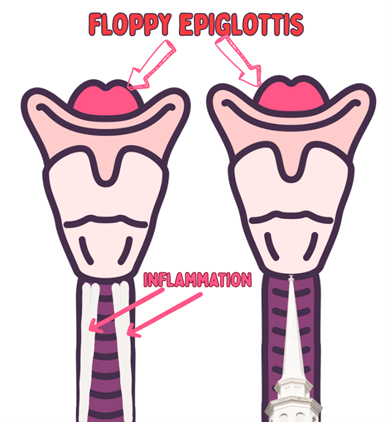

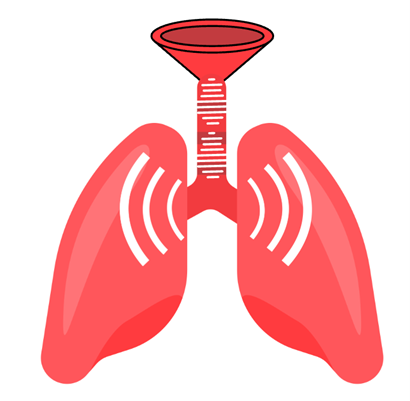

Croup causes inflammation and narrowing of the upper airway, restricting airflow and creating a “funnel effect.” If you were doing an anterior X-ray, you would recognize this as a “steeple sign.”

So why the sound changes, and why was there a “wheezing” sound in the upper part of the lungs but not so much in the lower part? That has to do with the funnel effect. It is always a good habit for everyone to auscultate the neck after auscultating the lungs; you can have resonance from the upper airway down into the lungs, being that they’re just large airbags connected to the top, by a large tube, a structured tube, the trachea. Being a corrugated pipe, it can resonate sound very easily from the upper part down into the airways.

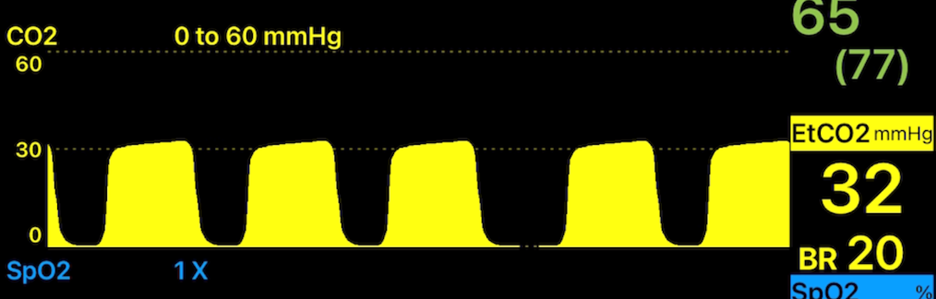

In Elijah’s case, you hear the constriction from the strider in the upper airway resonating down to the lungs, which sounds like isolated upper lobe wheezing. We confirm it is not wheezing because we have a large area where the sound is influencing (the top half of each lung), and there is no change in the end-tidal waveform. Large areas of wheezing would cause changes in the end-tidal wave due to the summation of a large area of bronchoconstriction.

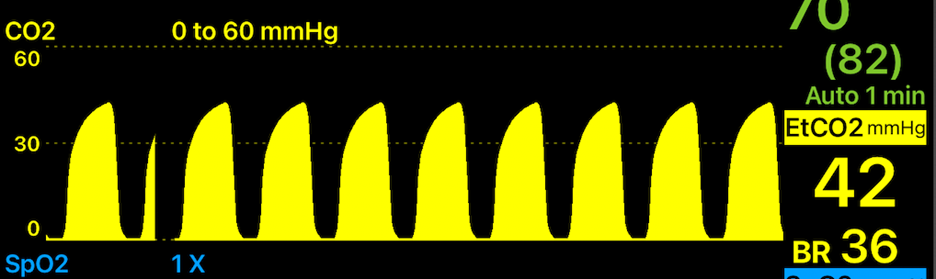

Unlike below, which is bronchoconstricted (notice the loss of the C phase?).

Once we’ve ruled out foreign body obstruction, treatment focuses on reducing inflammation and swelling, which in turn lowers airway resistance and eases the work of breathing.

Nebulized epinephrine (or Racemic Epinephrine) works by causing vasoconstriction and drying, reducing swelling and inflammation.

You can also follow up with a steroid (e.g., dexamethasone) to provide longer-term relief. This is commonly pushed to the ED in the event it is missed, epiglottitis, to prevent more stress from IV placement and/or IM administration.

Another critical consideration for upper airway issues in children especially is epiglottitis, which is a rare but serious condition. These patients are commonly between the ages of two and seven, prefer to sit upright and refuse to lie down, avoid swallowing due to pain, leading to drooling, and commonly have upper airway sounds like stridor. They have a swollen and inflamed epiglottis that for them is already large and floppy. Hence, the field diagnosis challenge of Croup vs. Epiglottitis and the passive treatment. Epiglottitis can be bacterial, viral, fungal or traumatic.

You’ll often see a wet collar, bib, or shirt. If clothing has been removed, ask the parent whether it had visible wetness around the neck, which may indicate drooling associated with epiglottitis.

In those cases, minimal stimulation and calm transport are critical.

More from the Author

Friday Night Lights: Shift 14 – Wet Whistles and Steak

Friday Night Lights: Shift 13 – Sweet Dehydration

Friday Night Lights: Shift 12 – Less Isn’t Always More

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.

As always, great information. Simple breakdown. Check out Chris’ other articles!