All images provided by the author.

It’s another Friday night, and the air is cool. Nothing is nicer than the fresh soft warmth of a new job shirt. This will be the first shift you get to break this one in. You hop in the rig, look over at your partner, and ask the age-old question: “Whatcha want for dinner?” But before they can answer your CAD chirps.

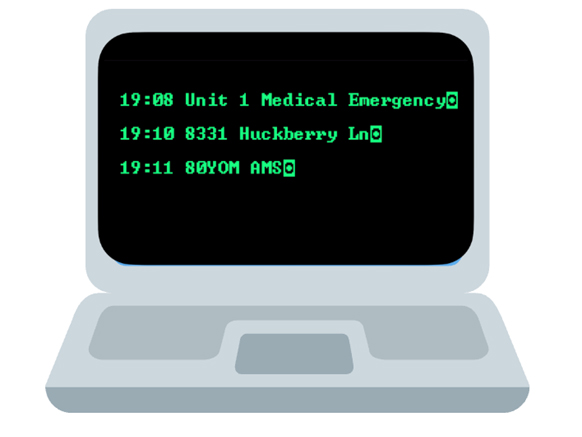

You’re being dispatched to a neighborhood for an 80-year-old male with an altered mental status. You mark en route and head towards 8331 Huckberry Lane. You arrive on scene to find a family of four standing at the front door, waving you in.

You grab your bag of tricks and box of life and head up to the front door of the split foyer home, which from the road looks like it’s frozen in time from the 60s. You’re greeted by four frantic family members who found their father/grandpa/pop pop/paw paw, mumbling and lying next to the couch on the living room floor. You pause for a second because there is a smell that catches your attention. At the same time, the CO alarm on your box of life starts alerting.

You look to the family and ask when they arrived as you grab the patient and start pulling him outside, encouraging them to follow. You begin assessing the patient in the front yard, and they state they arrived about five minutes before calling 911 and were on their way to pick him up for their Friday night family dinner in town.

They had not heard from him since 4 p.m. It is now 7:15 p.m. You look up at them and ask if any of them feels sick, and the young daughter says she has a headache. You get on your radio and request the fire department and a second transport unit. You ask the patient’s name, and they reply, “Frank Duncan.”

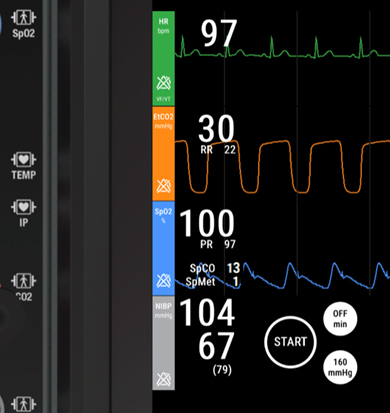

You ask Mr. Duncan if he can squeeze your fingers; he does so gently. You then ask Mr. Duncan if he can smile, open his eyes, and look up. He does it slowly. You ask the family if anybody else lives with Mr. Duncan or if he has any pets, and they say no. You ask your partner to do a 360 of the house while you’re going to hang out with Mr. Duncan. You get them hooked up to your monitor and find the following.

What are your primary concerns?

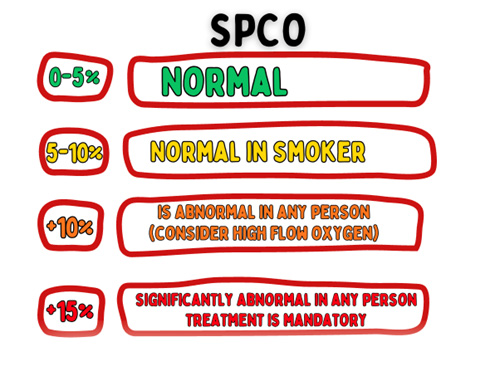

You get your oxygen out and put 10 LPM NRB on Mr. Duncan, knowing that one of the values on your monitor isn’t as accurate as it appears. At about the same time, your partner comes back around and says the home is gas-fed. He turned it off with his foldable pocket pliers, but the car might be running in the garage.

You let him know, OK, and you both agree to leave the front door open and ask a family member. If, by chance, the back door is open, they say no. “Papa always makes sure his doors are locked”, but they have a key and they can open it if needed.

You ask them to go around back, unlock the door, and open it so you can get some cross-ventilation until the fire department arrives, but to make sure that they do not go inside the home. They agree and step away.

You get back to the your partner pointing out the monitor as you gesture for them to bring the card over you can hear the sirens of the firetruck and other ambulance down the street you turn to the young girl who said she has a headache asking her her name and letting her know there’s another group that’s going to become coming to check her out and make sure her headache is OK.

She smiles and says thank you, but is sitting down next to Paul, holding her head clearly and in discomfort, your partner arrives back with the car lowering it down to ground level and glances over at the monitor again while you’re gathering a blood sugar and temperature

How’s your partner move to the head of the cot before starting to lift the patient? They tapped the oxygen cylinder and give you the up gesture. You look back at the monitor and agree to bump it up to 15LPM; the blood sugar comes back with the following results. Does this change anything?

You asked the family of Mr. Duncan if he smokes at all, and they adamantly refuse that he hasn’t smoked in over 25 years. You ask if he has any medical problems or takes any medicine, and they state he has gout, takes a pill for that, but has no drug allergies.

And you reconfirm as your partner counts to three before lifting the patient, that the last time they heard from him was 4 p.m. this afternoon, and he had no complaints. They confirm that it is accurate because they were ensuring he got home from his 3 o’clock appointment at the DMV and that he was still on board with going out to dinner.

You hear the hum of a diesel engine pull up and the air brake kick on as you package Mr. Duncan. The officer of the engine comes up and asks what they can help with, and you let them know that your CO alarm went off when you entered the home, and it appears as if the patient’s car has been running in the garage.

The unit officer says, “Gotcha, do you need any help loading or lifting?” and you say that you are good. The officer turns back to the crew and says, “Gear up and get the meters.” It sounds like a gas leak. The second ambulance arrives, and Sara, the OIC, heads up directly to you, asking what you need help with. You let her know that Cara, who was also in the house, has a headache and feels weak. You let her know that your CO alarm went off when you first arrived.

You get Mr. Duncan loaded up in the back of the unit and notice he’s starting to wince at your ultra-bright overhead light. He is still just mumbling and overall weak, and you poke your head up front to confirm with your partner that University still has a hyperbaric chamber. You get the IV quick and start a fluid bolus.

You hear a knock on the side door of your unit, and it opens. The engine officer pokes his head in and lets you know that it appears the vehicle (a late-model SUV) had been running in the garage, and they were getting about 200 ppm of carbon monoxide on their meters. They are going to ventilate the house and correspond with the family remaining on the scene. You thank them and tell them you’ll catch them later?

You turn and holler to your partner that they can go ahead and start as you grab the phone to make a call to university. While you’re waiting for the hospital to pick up, you turn to Mr. Duncan and let him know he’s in good hands, then ask him how he’s feeling. He mumbles an incomprehensible statement.

So, what is going on with Mr. Duncan?

What we see here is something that’s not that uncommon. In a world where cars are now controlled by FOBs, adults and children can accidentally start the car by finding the fob and clicking whatever button sequence initiates ignition for the “pre-warm-up” phase. They may have it in their pocket and roll onto it, or bump it with their wallet, etc.

Paired with the efficiency and quietness of cars, it isn’t uncommon for people to get out and forget to turn off the car, as car manufacturers changed this sequence of either starting or the alert when the vehicle is in park, the driver’s door opens to turn off the car, or that the ignition is on Earlier.

Models didn’t always have this. Some of the fixes you see are multiple button pushes on the fob, with a hold period of 5 to 6 seconds, etc. Mr. Duncan left his car running, or started it accidentally, and it continued to exhaust throughout the house.

With newer cars, you’ll see the pre-warm sequence after being started by a FOB now only stays on for a specific period of time, whether it’s five minutes or 10 minutes, and then cuts off to prevent the situation we are in with Mr. Duncan.

As you entered the home, your carbon monoxide alarm kicked off, and you were also presented with a family who had been experiencing symptoms. Because of the exhaust from the vehicle in the lack of true compartmentalization of a garage and a home, the products of exhaust migrated into the living space of Mr. Duncan’s house.

The exhaust has a high concentration of carbon monoxide, causing a cascade of effects on Mr. Duncan and his family.

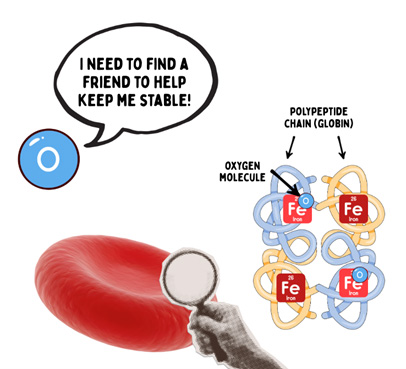

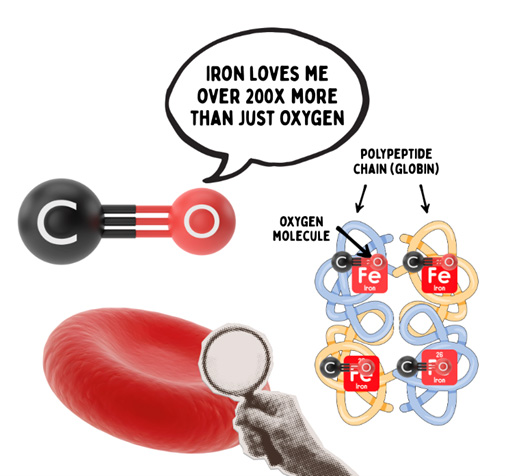

Carbon monoxide is an odorless, colorless, tasteless gas and is a product of combustion. Carbon monoxide also has a high affinity for the iron-binding sites on your hemoglobin, about 250 times more than O2, meaning that the bond between carbon monoxide and the iron is tough to break once it is bound to your hemoglobin.

Because of its reluctance to leave the hemoglobin at the end-organ tissue, and due to changes in the partial pressure of oxygen both in the blood within the lungs and in the tissue, we don’t get proper offloading and onboarding of oxygen as we would with O₂.

Hence, the tissue becomes toxic. In this case, it is hypemic hypoxia, meaning the blood cannot carry enough oxygen because carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin, preventing oxygen transport to the tissues.

By the tissue not receiving oxygen, tissue function worsens, leading to dilation of blood vessels. This is evident in the late stage of carbon monoxide poisoning, where the capillary beds and arterioles dilate, resulting in a cherry-red appearance.

The heart becomes floppy, and the metabolism initially tries to increase to compensate, but then becomes sluggish due to poor cellular function and inadequate oxygen delivery compared to consumption.

Blood pressures increase then decrease, and respiratory rates rise due to the introduction of oxygen into the circuit, as well as the support of the vascular system by drawing blood back into the core through the negative pressure breathing cycle we’ve discussed, including previous Friday Night Lights cases.

We also get falsely high SPO2s. And technically, they’re not falsely high because there is oxygen on the hemoglobin. It’s just that your average pulse ox doesn’t look for carboxyhemoglobin. It looks for oxyhemoglobin, which is detected at a different wavelength.

In the presence of individuals with conditions such as tachycardia, lightheadedness, and areas of combustion, a perfect SPO2 reading should raise suspicion of carbon monoxide poisoning. What is the treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning? What is your treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning? What are your therapeutic endpoints? What is your transport destination and why?

Keys to treatment. Remove them from the environment! This also means don’t pull them out of the IDLH into the yard next to idling and exhausting emergency equipment.

Fresh air is key! Oxygen is the friend of CO poisoning. If symptomatic, then high-flow oxygen and perfusion support are the priorities. If unconscious, high-flow oxygen is critical, as well as optimizing ventilation.

High-flow oxygen is delivered to saturate the system and attempt to overcome CO binding. In extreme cases, HBOT (hyperbaric oxygen therapy) isn’t mandatory, but it has shown benefits in removing CO from the hemoglobin and reestablishing oxyhemoglobin more quickly.

It increases dissolved oxygen content in blood (plasma) and accelerates the elimination of carbon monoxide. The catch being acute HBOT chambers aren’t as common as the smaller versions used for wound care, Lyme’s treatment, etc.

The larger acute chambers must be able to accommodate intubated patients and also provide sufficient space for clinicians to be present within the chamber with the patient in case of an adverse event.

Picture of the chamber at Shock Trauma in Baltimore, Maryland.

To recap, let’s consider this shift case. The key to treatment after recognition is removal from the environment, high-flow oxygen delivery, and perfusion support.

More from the Author

Friday Night Lights: Shift 16 – Smoky Nights

Friday Night Lights: Shift 15 – Squeaky Peaked Exits

Friday Night Lights: Shift 14 – Wet Whistles and Steak

Chris Kroboth has been a career paramedic/firefighter for over 17 years and in EMS for over 23. He has been in prehospital and in-hospital education for the past 18 years. His last assignment before returning to operations was as the EMS training captain in charge of continuing education programs and certification. He is also affiliate faculty with the Virginia Commonwealth University Paramedic Program. He is the U.S. clinical education manager for iSimulate and also facilitates national conference clinical challenges to include EMS World, ENA and NTI.