COVID-19 has called attention to the dangers of ventilator circuit disconnects. Transferring a mechanically ventilated patient from an intensive care unit (ICU) to EMS vent poses potential life threatening risks of infection to everyone in the vicinity. In the absence of infection disease concerns, disconnecting a vent circuit results in withdrawal of all ventilatory support, potentially allowing alveoli to collapse. In order to avoid cross-contamination of health care workers and lung de-recruitment, clamping of the endotracheal tube (ETT) has become a gold standard practice.1

Avoiding lung de-recruitment in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is of particular concern. The ARDS population is typically ventilated with high PEEP pressures to augment oxygenation and attempt to keep driving pressures lower by finding an optimal PEEP level. The pathophysiology of ARDS results in heterogeneous lung collapse, unstable alveoli, and edema filled airways.2 Because of these conditions, most clinicians would agree that removing pressure leads to complications oxygenating and ventilating these patients. The ARDSnet protocol typically uses PEEP levels anywhere from 8-24 cmH2O and an FiO2 of 1.0. Removing the pressure for even a few seconds causes the PEEP level in the lungs to drop to zero. It may take hours to re-recruit the alveoli to the PEEP setting in place before disconnecting the circuit. During this time, hypoxia may drastically worsen.

Related: Increasing Intubation First-Attempt Success Rates in Patients of All Ages

In the neonatal ICU (NICU) it has been common practice to clamp the ET tube prior to any disconnect for patients with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) who are being mechanically ventilated using a high frequency oscillator (HFO) or high-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV). These types of ventilation target a mean airway pressure (MAP) or PEEP and oscillates or pulsates a breath that is less than dead space ventilation. The MAP or PEEP are set to maintain lung volume targets determined by chest x-ray (CXR). When the circuit is disconnected, allowing the MAP or PEEP to drop to zero, it often takes hours to reach the original lung volumes prior to disconnect.

More recently, clamping the ET tube became common practice for ventilated persons under investigation (PUI) and known COVID-19 positive patients. When transferring an intubated patient from a hospital ventilator to a transport ventilator, the goal is to minimize or eradicate any exposures to aerosolized respiratory secretions. One suggested strategy includes placing a bacterial/viral filter on the end of the ET tube. This seems sound in theory but invariably, patient secretions require intervention (suctioning). In-line suction catheters resolve the need for circuit disconnects but an in-line catheter cannot pass through a bacteria/viral filter. In such cases, the ET tube should be clamped when not connected to a filtered ventilator circuit. Clamping the ETT reduces aerosol particle dispersion and protects people in the vicinity.3

Related: Prehospital Critical Care for COVID-19 Patients

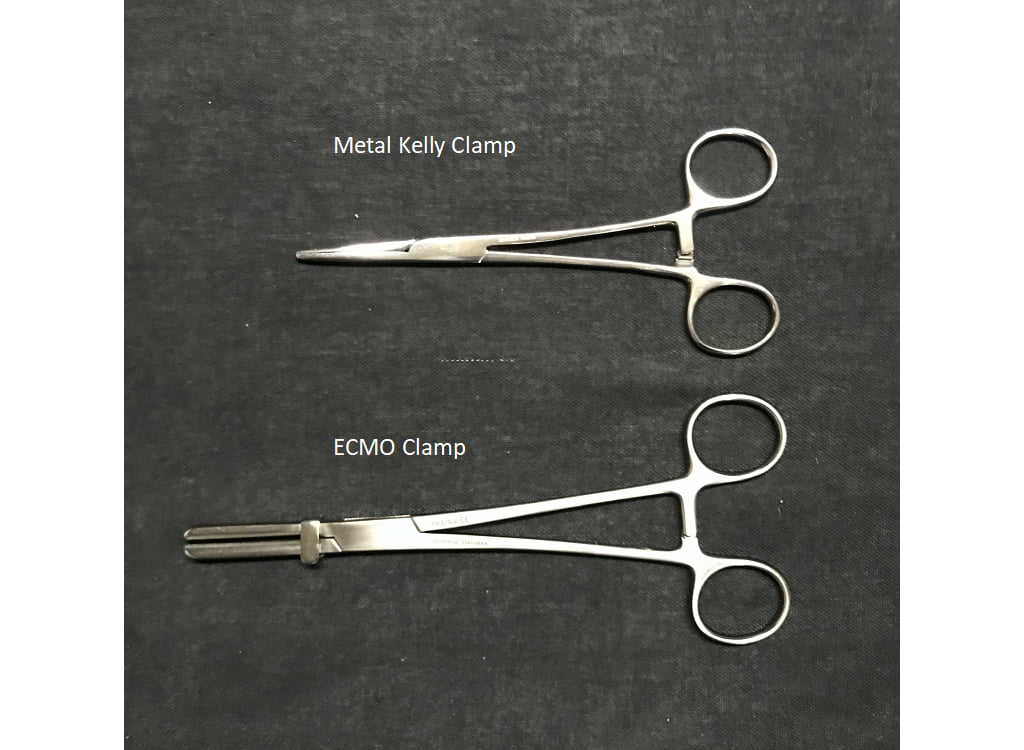

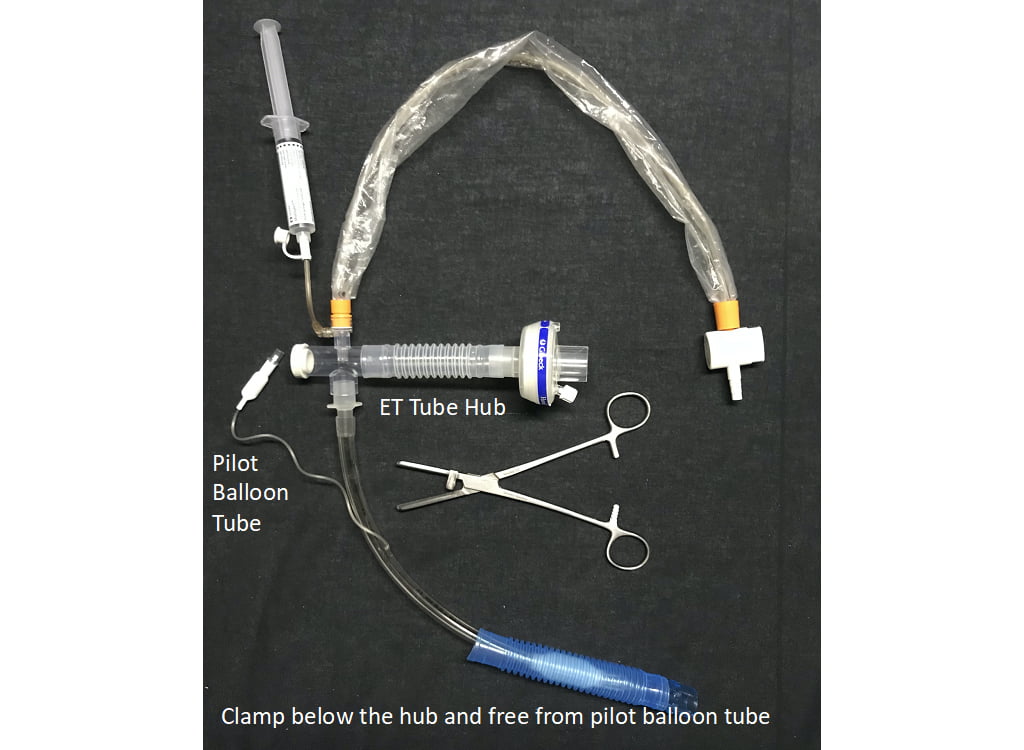

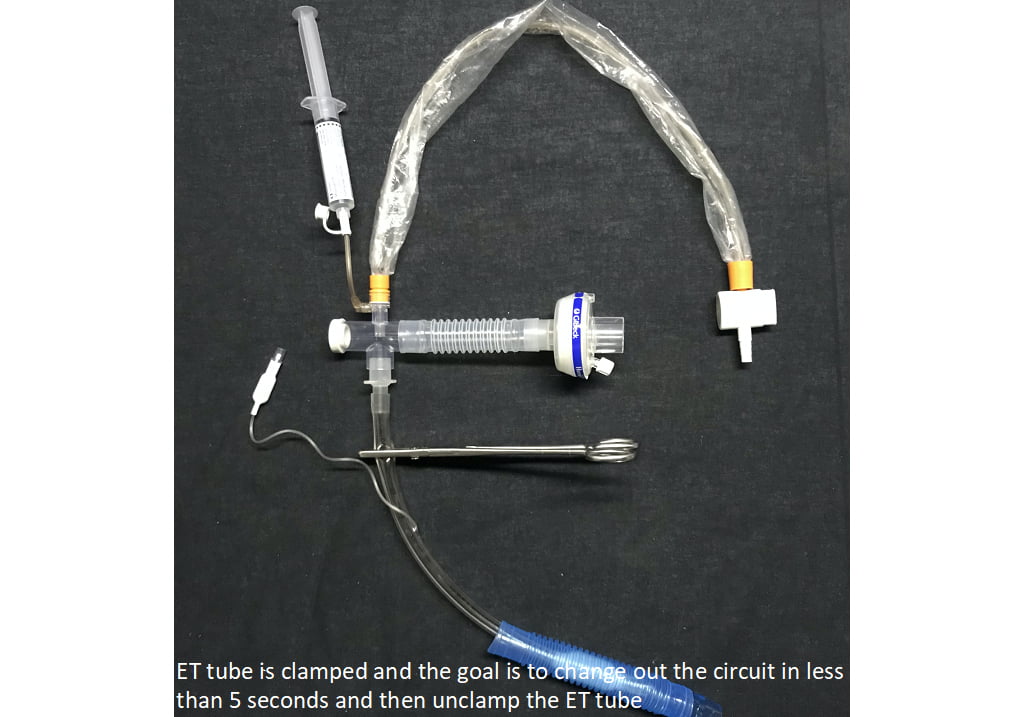

Although clamping an ET tube may sound like a simple maneuver, research shows this may not be the case. A recent bench study looked at three types of clamps along with three types of ET tubes, measuring airway pressure and flow between the distal end of ET tube and the lung model. The clamps used were an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) clamp, a metal clamp and a plastic clamp. The study demonstrated that only the ECMO clamp sufficiently occluded the ETT due to its size and its stronger clamping ability.4 The ET tubes used in the study were an oral/nasal tube, a nasal tube and a reinforced tube (anode or spiral-metal bound ETTs). After clamping, the reinforced tubes had persistent increases in airway resistance. Hence, it is not recommended to clamp a reinforced ET tube as this may lead to permanent occlusion.

Photos courtesy Vent-Pro Training.

There are risks associated with clamping an ETT on an awake, alert and spontaneously breathing patient. It may potentially increase the risk of negative pressure pulmonary edema (NPPE) resulting from increased negative intrathoracic pressure from the patient’s inspiratory efforts working against the obstructed upper airway.5 To reduce the risk of NPPE, some would suggest significant levels of sedation prior to the transfer of circuits.6

Any skill to be mastered entails significant practice. It is suggested to rehearse effectively clamping and unclamping an ET tube on a mechanically or manually ventilated manikin. Limiting disconnection from the ventilator to less than five seconds to change over circuits while the ET tube is clamped and unclamped is the ultimate goal, preserving safety and comfort for your patient. While essential for safety or providers and protection of your patients, clamping an ETT is a skill that requires the proper equipment (ECMO clamp) and practice. Any intubated patient should have a clamp nearby in case of circuit disconnect and every provider caring for the patient should be trained and capable of clamping the circuit should need arise.

References

- McCormick T. Clamp to prevent collapse. Anesthesia. 2010; 65:861-2.

- Nieman, G.F., Andrews, P., Satalin, J. et al.Acute lung injury: how to stabilize a broken lung. Crit Care 22, 136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2051-8

- Cook, T.M., El‐Boghdadly, K., McGuire, B., McNarry, A.F., Patel, A. and Higgs, A. (2020), Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID‐19. Anaesthesia, 75: 785-799.https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15054

- Turbil E, Terzi N, Schwebel C, Cour M, Argaud L, et al. (2020) Does endo-tracheal tube clamping prevent air leaks and maintain positive end-expiratory pressure during the switching of a ventilator in a patient in an intensive care unit

- Bhattacharya M, Kallet RH, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Negative pressure pulmonary edema. Chest 2016; 150: 927-33.

- Lockhart SL, Duggan, LV, Wax, RS, Saad S, Grocott HP. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for both anesthesiologists and other airway managers: principles and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anesth 2020; 67; 1005-15.

Michael Schauf, RRT-NPS, has been a registered respiratory therapist at Albany Medical Center Hospital in New York since 1994. He covers all in-patient units, ICUs, the adult and pediatric Emergency Departments and is a member of the neonatal/pediatric transport team at this Level I Trauma and Level 3 NICU Center. Michael is the founder of Vent-Pro Training, teaching medics and nurses around the world how to manage mechanically ventilated patients during ground, rotor, and fixed-wing transports. He has been a flight respiratory therapist since 1998, currently working for AirMed and as a clinical education specialist for AMR. Michael authored the respiratory chapter of, “Critical Care Transport, 2nd edition,” published by Jones & Bartlett and is an adjunct instructor in the Respiratory Care Program at Hudson Valley Community College.