Images created by the author.

Few procedures in the prehospital environment are as anxiety producing and stressful as a surgical cricothyrotomy. As dangerous and stressful as it may be, it is a critical and essential tool in any airway management toolkit.

This title is a little bit misleading in that it creates an expectation that there is some new practice changing information about emergent front of neck access (eFONA) for paramedics in 2024.

There really is not. The evidence does not suggest that this is being executed any worse or any better than in previous years. It is still wrought with risk of complications, morbidity and mortality. The mainstays of success with this procedure are training and technology.

Better training and technology can reduce the risk of poor outcomes with eFONA, but the mental models and systems we have in place to employ this skill are of equally paramount importance.1-2 That is where this article will focus.

Throughout the industry, eFONA is considered a “HALO” procedure, or High Acuity Low Opportunity skill. Meaning that it is a highly dangerous or invasive skill that we do not have many opportunities to perform to become facile with it. The training and mindsets with which we approach this procedure are paramount to its successful execution.

Rumor Control

Can’t Intubate / Can’t Oxygenate (CICO): this terminology has started to fall out of favor. So much so, that the Canadian Airway Focus Group recommended a change in how we trigger the decision to use eFONA from CICO to Can’t Intubate/Can’t Ventilate (CICV).1-2 Why the pivot?

Because words matter. Oxygenation is not solely dependent on intact and functioning airway anatomy.1-3 In fact, delivery of oxygen is largely driven by cardiac output and a trigger of “can’t oxygenate” can lead to an unnecessary invasive means of managing the airway, when in fact the patient needed more aggressive resuscitation to improve oxygenation.3

CICV more accurately represents “why” a prehospital clinician may need to select eFONA as a means of securing the airway.1-3 It is better aligned with what eFONA is meant to accomplish; secure the airway and restore ventilation when intubation is not successful. Bick et al. suggest that eFONA only improves oxygenation when there is a functional supraglottic failure of the airway anatomy, which this procedure would directly address.3

Avoid eFONA at all costs: not every patient requiring airway management will present in a manner that allows a prehospital operator to work iteratively through their airway management tools and algorithms. Sometimes the patient presents in extremis and any attempt at supraglottic access and management of the airway is impossibly futile.

A mindset of eFONA as a procedure that should be “avoided” risks prioritizing futile attempts at airway management in order to satisfy an algorithm rather than prioritize what the patient needs in that instant.3

Much of the morbidity and mortality associated with eFONA is due to anoxic brain injury due to prolonged time without ventilation/oxygenation. Specifically, the time it takes to make the decision to access the airway through the neck can mean the difference between a viable patient and one that will suffer a devastating anoxic brain injury. While there absolutely is a good reason for eFONA to not the primary approach to securing the airway in most cases, prehospital clinicians should avoid mindsets where eFONA is something to be avoided at all costs. Instead, they should work to be able to recognize when they are beyond the point where the “standard” approach is of any benefit and be prepared to appropriately escalate their care to meet the patient’s needs.

Mindsets and Mantras for Executing eFONA

At the Big Sick ’23 conference, Dr. Richard Levitan’s presentation dispelled some of the myths and rumors surrounding the performance of eFONA in the emergency medicine environment. He provided a series of “mantras” to reframe the way we approach the decision making and the execution of the incision in someone’s trachea to place an airway.4

The presentation can be viewed here.

1. To save a life, I have to use a knife4.

The decision to make the incision is often what takes us the most time in the overall execution of the process. The procedure itself it relatively simple and straightforward: scalpel, finger, bougie being one example of the simplicity of eFONA. To that point, the decision to place a surgical airway is not one that is made in the heat of the moment when you suddenly realize that you are at the end of the algorithm. This is a decision that has to be made as you assess the patient’s airway and as the likelihood of having to perform this procedure becomes more and more apparent.

eFONA typically lives at the end of the airway management algorithm. As more difficulty is predicted in the assessment, the further up the algorithm the triggers for eFONA should be elevated. Sometimes, the patient is at the end of the algorithm when we get to them. These decision triggers must then be cemented in “If This/Then That” preplanning and deliberately communicated to the team so that there is no doubt or confusion as to what the operator’s intentions are once a trigger point has been surpassed. This speaks well to a quote from Dr. Levitan: “Predicting difficulty is much less important than knowing what to do when it is encountered.”4

2. Laryngeal Handshake…4

“There is a hesitation to start (the procedure) if you can’t (identify) the landmarks.” – Dr. Levitan. 4

The Difficult Airway Course teaches several external exams to ascertain the level of difficulty likely to be encountered.5 With eFONA the assessment is designed to answer two questions:

- “Can I locate the midline of the neck?”

- “Can I palpate the cricothyroid membrane (CTM)?”

Contrary to mainstream teachings, finding the CTM is not the first step in eFONA… finding the MIDLINE of the neck is. Hence the laryngeal handshake. The middle and ring finger of the non-dominant hand grab the larynx on either side of the thyroid cartilage leaving the index finger free to be placed straight down on the neck. More specifically, the midline of the neck. From there the operator can palpate the CTM and find the site for eFONA.

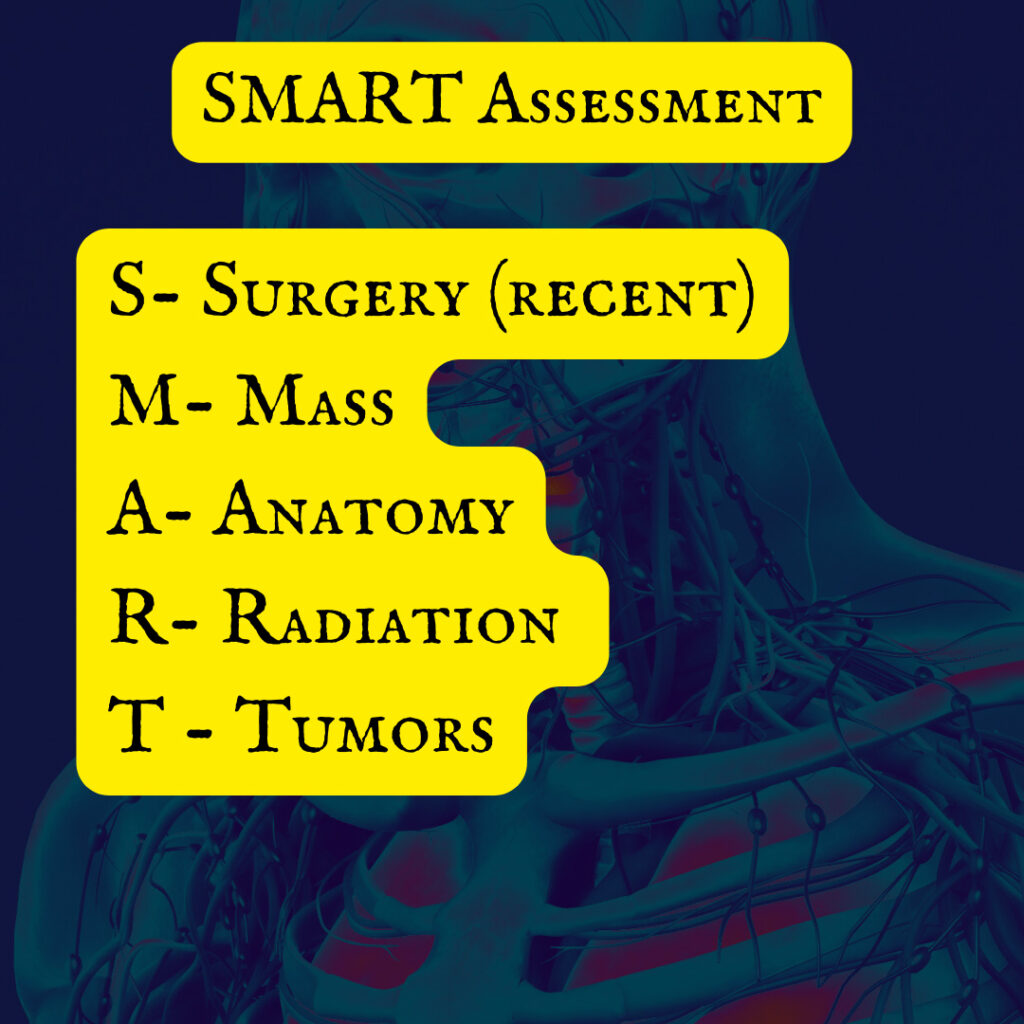

This is a simplistic explanation and is only that simple if one of the SMART assessment findings is not present. The SMART assessment, taught in The Difficult Airway Course, is an external clinical exam to find any anatomical/pathological problems that will prevent the operator from finding the midline of the neck. For example, a patient with a large neck circumference and a lot of mass on the anterior neck would make it difficult to find the CTM by palpation alone, if at all.

Here we uncover a fundamental flaw of eFONA training. “We should all be able to palpate the CTM and find it on every patient,” as though that were possible. The presence of any of the SMART criteria for difficult eFONA is an independent predictor of difficulty in eFONA placement. Inability to palpate the CTM is not the only difficulty with eFONA SMART criteria… surgeries and tumors can be present in the area of the CTM and make locating it after the initial incision quite difficult. Trauma to the larynx that causes disruptions to the anatomy can also make eFONA incredibly difficult.

There is a psychological advantage to using the laryngeal handshake. Primarily, it offloads the need to satisfy, 100%, that the CTM has been located before the initial incision. An operator who either cannot palpate or experiences great difficulty in doing so loses psychological momentum (read: confidence) in their ability to successfully complete the procedure.

The allostatic load increases, as does the physiologic response to the stress. Dr. Levitan asserts that most operators will hesitate longer to get started if they cannot successfully palpate the CTM landmark. A simple reprioritization of finding midline then finding the CTM both reduces time to execution (and with it the risks of anoxic brain injury) and protects the mental performance of the operator.

Wrap Up

In Part 1 of this 2-part series on eFONA, we have uncovered a few poor conceptualizations and mindset traps associated with this procedure. In Part 2, we will unpack the PLACE acronym and get into the bloody weeds of emergency front of neck access.

References

1. Law JA, Duggan LV, Asselin M, Baker P, Crosby E, Downey A, Hung OR, Jones PM, Lemay F, Noppens R, Parotto M, Preston R, Sowers N, Sparrow K, Turkstra TP, Wong DT, Kovacs G; Canadian Airway Focus Group. Canadian Airway Focus Group updated consensus-based recommendations for management of the difficult airway: part 1. Difficult airway management encountered in an unconscious patient. Can J Anaesth. 2021 Sep;68(9):1373-1404. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02007-0. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34143394; PMCID: PMC8212585.

2. Law JA, Duggan LV, Asselin M, Baker P, Crosby E, Downey A, Hung OR, Kovacs G, Lemay F, Noppens R, Parotto M, Preston R, Sowers N, Sparrow K, Turkstra TP, Wong DT, Jones PM; Canadian Airway Focus Group. Canadian Airway Focus Group updated consensus-based recommendations for management of the difficult airway: part 2. Planning and implementing safe management of the patient with an anticipated difficult airway. Can J Anaesth. 2021 Sep;68(9):1405-1436. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02008-z. Epub 2021 Jun 8. PMID: 34105065; PMCID: PMC8186352.

3. Bick E, Barnes J, Roberts J. Can’t intubate can’t oxygenate: It takes more than a patent airway to oxygenate a patient. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;37(6):503-504. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001143. PMID: 32379147.

4. YouTube. 2023. TRAUMA SESSION PT.1 and THE SCIENCE OF PRESENTATION – The Big Sick 23 {Video}. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C800Azwb2rg

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.