As we move through our journey from novice airway tacticians to expert airway strategists, we learn that there is much more to do than simply displace the tongue and insert a plastic tube into the trachea.

So much of success in airway management has to do with clinical reasoning and clinical judgement rather than the protocols, medications or instruments. That is what this piece will focus on.

These elements, which are debated ad nauseum, can certainly enhance our ability to control the airway, but there has been considerable difficulty finding a “silver bullet” solution that would render emergency airway management completely safe.

This is because of the difficulty of airway management in the clinical context of the prehospital environment, not in the tools, medications or protocols.

Why + When = Context

It is at the intersection of “why” and “when” that we find context. The complexity of prehospital airway management is not entirely predicated on the fact that a patient requires intubation outside of the walls of a hospital.

It is because of the pressures of why and when and how they either independently color a situation or concomitantly influence the context of the situation that prehospital airway management is wrought with pitfalls.

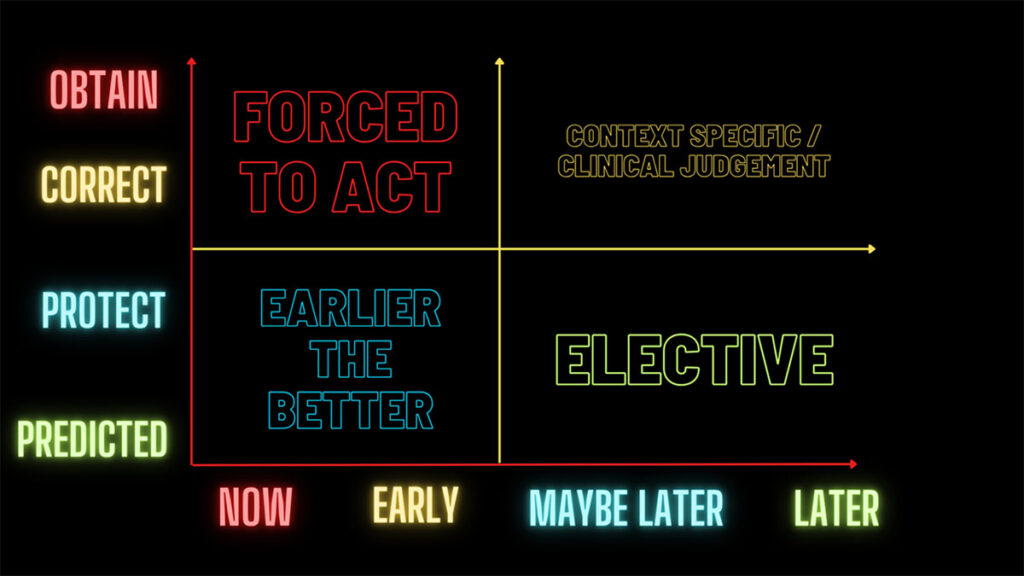

There are four contexts for prehospital airway management:

- Obtain + Now = Forced to Act.

- Correct + Early = The Earlier the Better.

- Protect + Maybe Later? = Judgement Call.

- Predicted Course + Later = Elective.

Each of these represents a certain level of acuity with which the patient is presenting, which then also dictates the “when” of the situation.1

Image created by the author.

1. Obtain + Now = Forced to Act

The forced to act context is the most serious and dire situation for the patient. The problem is a functional loss of airway patency. A decreased level of consciousness, foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO), or an inability to maintain airway protection secondary to swelling/edema are all typical situations in which airway control becomes paramount.

This type of scenario leaves no time for “should we”-type questions. Nor does it accommodate attempts to reason your way out of doing something. The patient needs an airway, and they need it now.

2. Correct + Early = The Earlier the Better

Perhaps the patient’s airway is functioning, but there is a pathologic process rendering their ventilation or ability to oxygenate ineffective. At this point the clinicians have to step in and control the airway in order to facilitate further resuscitation to restore normal ventilation or oxygenation.

Examples of this would include situations where the patient is not regulating their CO2 content and is slipping deeper into respiratory failure. Based on the clinical assessment, the clinician can see that the patient is in trouble now and that delaying airway management would only make things worse.

Another decision pathway in the “earlier the better” context is that the patient may not need immediate airway management but delaying it would mean that the physiologic conditions would be even less favorable than they are right now.

Instead of dealing with a stable patient with optimal physiologic conditions for airway management, the patient will likely deteriorate during the procedure due to the delay and worsening of their physiologic condition. Correct it early, or wait and the patient’s condition will deteriorate!

3. Protect + Maybe Later? = Judgement Call

In cases of anticipated loss of protective reflexes, a clinician may elect to preemptively intubate a patient to protect the airway. They have arrived at the question of “can they protect their own airway, or do I need to place a tube to do so?”

This decision is traditionally heavily weighted on the assessment of the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), however, this may not be as reliable as we used to believe.

The GCS was originally developed as an assessment of mental status and airway protection ability in trauma patients. It has since been extrapolated to include every patient encountered in the prehospital environment.2

At its inception, it was strongly supported because of the logical conclusion that the patient’s protective reflexes become less effective in tandem with a reduction in their level of consciousness. What we know now is that this is simply not universally true in patients requiring emergency airway management.

In an evaluation of a patient’s ability to protect their own airway, clinicians should evaluate the following factors:

- Are they aware of obstructions/secretions/fluids in their oropharynx?

- Are they trying to clear those obstructions/secretions/fluids? (coughing, sitting forward, etc.)

- Are they able to continue that effort for the long term, perhaps with minimal assistance (g., suction only)?

- Are they able to follow commands/answer questions?

4. Predicted Course + Later = Elective

In this context, the decision for airway management becomes elective rather than determined by protocol. The clinician has time to decide and weigh the risks of taking over someone’s airway.

And this is more than just time to think. It’s time to optimize the patient for the procedure. There is time to step back and look at the bigger picture.

Questions like the following govern this aspect of decision making:

- What is the potential for deterioration?

- Do I expect things to get worse in transport?

- Is there an operational context here that we need to consider?

The patient may not have a primary physiologic issue with their airway patency, ventilatory ability, or oxygenation; but they may, eventually, have one. The key here is to decide if there is time to delay airway management without making things worse for the patient.

If there is a decision to delay, will the procedure then have to be performed in a moving vehicle or aircraft? This can be less than ideal depending on several factors. If there is a delay, will the chances of successfully placing an airway become dramatically reduced?

In this situation a clinician is electing to manage the airway here and now, in anticipation of either worse (but not currently present) physiologic conditions, or to facilitate other aspects of treatment (e.g., intubation prior to delivery to the operating room for an emergent procedure).

Conclusion

The decision to take over (or not take over) a patient’s airway weighs heavily on those operating in the prehospital environment. Some organizations have very strict and prescriptive protocols for why and when to intubate while others have more liberal guidelines.

Regardless of how the policy or protocol reads, the patient must be placed into the proper context. It is only after we understand the situation that we can decide the when and the why.

This is not a call to ignore protocol or policy, rather it is a framework for thinking so those protocols and policies can be more accurately and safely applied.

More from the Author

Copy and Paste: A Case for Change

Undifferentiated Respiratory Distress: A Medic’s Guide (Part 2)

Undifferentiated Respiratory Distress: A Medic’s Guide (Part 1)

References

1. Kovacs, G., and Law, J. A. Airway Management in Emergencies. Langara College, 2012.

2. Ribeiro SCDC. “Decreased Glasgow Coma Scale score in medical patients as an indicator for intubation in the Emergency Department: Why are we doing it?” Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2021 Mar 8;76:e2282. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2021/e2282. PMID: 33681943; PMCID: PMC7920397.

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.