Human lungs. (Shutterstock/Explode)

“Respond for a 61-year-old male in respiratory distress…”

It is that time of the year again… respiratory distress season. The cold winter months are seemingly the harbinger of this common, and often, non-specific complaint. Sometimes EMS crews arrive on scene to a patient that is doubled over on the verge of unconsciousness.

Sometimes they arrive to find nothing more than someone who is sitting still providing deadpan answers with a dull expression that belies their complaint of “distress.” In this two-part series, we will get to the heart of what “I can’t breathe” may mean for some patients and how to pull the threads to dig deeper and find the root of the issue.

What Are We Dealing With?

With respiratory complaints, it is helpful to understand what you are dealing with. There is a reason that the patient is short of breath, and sometimes we can quickly discern their primary problem, while other times we have to do some digging. Most of our patients will fall into one of two categories:1-2

- New onset difficulty breathing with no known or apparent cause. For these, we must do quite a bit of digging, and in the prehospital environment a diagnosis may prove to be elusive by the time they get to the emergency department.

- An acute exacerbation of a known cardiovascular or respiratory disease.

The sensation of dyspnea has an underlying physiologic cause. The dyspnea itself is a symptom of an underlying issue. An increased respiratory rate or need for more volume comes from the need to either increase oxygen content or remove more carbon dioxide due to retaining it or needing to buffer their acid-base balance. But it gets clouded when the patient is disturbed and distressed by the sensation. Getting to the bottom of that underlying issue is the mission and the key to relieving

All Systems Go?

When we enter a home and lay eyes on a person complaining of dyspnea, we are not seeing COPD or asthma. We are seeing that dramatic interplay between the disease burden, the patient’s nervous system, and their cardio-respiratory systems. The point being the respiratory system does not work independently of the others1—and therein lies a hole in some of our training.

Dyspnea is a symptom of an underlying problem. The perception of dyspnea is difficult to convey if one is not educated to do so. The patient does not know what

The patient experiencing an acute COPD exacerbation is having a problem with air flow due to bronchoconstriction (there is also inflammation and mucous production at play as well). That problem gives the sensation of “not getting enough air,” which for most normal humans triggers an anxiety response.3

Meaning, the respiratory drive is taking two hits: one from the anxiety of “not getting enough air” and the other from the disease burden from the bronchoconstriction.1,3 Things only get worse until they feel relief from the anxiety and improved ventilation. This may be counter to seeing the right “numbers” on the monitor.

The point is to get beyond simplistic thinking like: “the respiratory drive is based on a negative feedback loop,” or “the need to breathe is driven off of the level of carbon dioxide in the blood.”

Both statements are inherently true, there is no dispute in these simple descriptions of human physiology, but in dealing with those with respiratory complaints we have to get deeper into applied physiology and understand the interplay between core principles like this and the various organ systems that govern their activity (more on this in Part 2).

Meaning, how are the nervous system, cardiovascular system, and respiratory system related? What do they need from one another? How does one influence the others? What makes all systems go?

What Are They Telling You?

As we work through the assessment, certain words and phrases can point us toward what the patient is experiencing. Dyspnea is a completely subjective experience for the patient.3

The perception of dyspnea is difficult to convey if one is not educated to do so. The patient does not know what we need to know about their underlying physiology and pathology, and there is a “language barrier” there creating difficulty in conveying the depth and severity of their problem.

That “language barrier” is that the patient does not know our terminology or the key words that we are looking for, and often can only generally explain the way they feel.

For example, it is rare that a patient looks at the clinician assessing them and says: “I have bronchoconstriction and a mucous plug.” We have to ask the right question in the right way to elicit the answer we need.

We are trying to pry and get to the heart of their issue, and in so doing we can help relieve the discomfort of not being able to breathe normally. If we ask leading questions their answers are likely to lead us nowhere.

Better questions like: “do you feel like you cannot get a full breath, or do you feel like you are not getting enough air” are more helpful into fully developing the differential diagnosis lists.

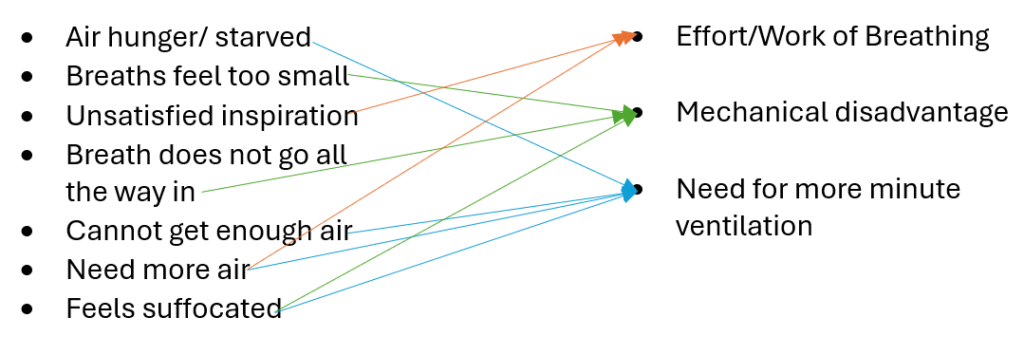

Their answers should point to one of three main issues that are causing the dyspnea (note that it is entirely possible they have all three present at the same time as well):1-2

- Strength or effort (too weak to move air or too weak to move enough air)

- Mechanical disadvantage (like narrow airways)

- Need for more minute ventilation

When we ask them to quantify how they are feeling, we need to listen for phrases that describe these sensations:1-2

- Air hunger/starved

- Breaths feel too small

- Unsatisfied inspiration

- Breath does not go all the way in

- Cannot get enough air

- Need more air

- Feels suffocated

Here is how we can match the patient’s description to the cause of the dyspnea:1-2

Image created by the author.

For a more simplified way to look at what the sensation being described indicates1-3

- A description of increased effort or work of breathing indicates a problem with respiratory strength. This describes an uncomfortable sensation of work or effort. These types of issues are common with COPD/Asthma and other issues with respiratory muscles. The brain is receiving a signal that the respiratory muscles need to do more work to get a breath, which leads to a sensation of increased effort.

- A sensation of tightness indicates a problem of a mechanical disadvantage (like narrowing of the airways). Tightness with a sensation of increased effort and air hunger leads the patient to feel like they cannot get enough air in due to the narrowing of the airways.

- A sensation of air hunger indicates a need for more minute volume. The patient’s demand exceeds their capacity to meet their needs. This is in incredibly uncomfortable sensation, and it is intensified by hypoxia, hypercapnia and acidosis.

Now that we know what they mean when they say, “I can’t breathe” or “I feel like I can’t catch my breath,” we know how to better attack their problems and provide them with relief of the suffering of not being able to breathe normally.

Above All, Be a Good Listener

We have asked our questions and listened to what the patient had to say, but we are not finished. We still need to listen to what the lungs have to say, and the physical assessment is still outstanding. Auscultation of breath sounds provides us with an awareness of what may be the primary pathologic process:

- Clear

- Wet (indicating rales/ronchi)

- Wheezes

- Absent/Diminished

Again, beware: Can these sounds co-present with each other? Absolutely. Is a wheeze always bronchoconstriction from asthma or COPD? Not every time. Absent or diminished breath sounds can be as simple as poor instrumentation and placement, or a sign of a much bigger problem.

Avoiding bias and anchoring on something simply because it matches a heuristic is an easy way to miss the real problem.

What Do We Know Now?

Perhaps we know why they look the way they do? By this point in the patient care episode, we should know what it means when the patient says: “I can’t breathe.” We should know how it is making them feel, this sensation of breathlessness.

Their posture, their effect, and the tone/timbre of their speech gives you a glimpse of how distressing the episode is for them.3 Some people can wheeze, and they are seemingly fine with it, even cracking a joke during their 2–3-word dyspnea. Some people are in total panic because they cannot cope with the fact that they are “short of breath.”3

We also have some glimpse into the inner workings of their chest and lungs with our auscultation of their breath sounds. We should have a reasonable suspicion of their primary problem—be it bronchoconstriction, pulmonary edema or pus from an awful pneumonia.

But what we do not know is the full extent of the disease burden. Rounding out the assessment with end-tidal CO2 monitoring (ETCo2), pulse oximetry, and blood gasses tell us the extent of the physiologic impact.

Hypoxia, hypercapnia and acidosis are the three horsemen of an impending respiratory apocalypse and require prompt identification and treatment.

In isolation, these numbers are simply that, just numbers. The prudent clinician must put these together to create as complete a clinical picture as possible. Then from there can create the best solution for that patient based on where they are now.

Conclusion

In Part 1 we have unpacked the deeper meaning of “respiratory distress” and what it may actually mean when a patient says “I can’t breathe.” It is important to remember with respiratory complaints that nothing can be taken in isolation (vital signs, breath sounds, etc.) as the cornerstone for a treatment decision.

Cognitive bias is a real risk here which carries the possibility of under or over treating these complaints, all the while neglecting to provide the patient any relief of their suffering.

Stay tuned for Part 2 where we will pull apart respiratory distress and respiratory failure.

References

- Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, Calverley PM, Gift AG, Harver A, Lareau SC, Mahler DA, Meek PM, O’Donnell DE; American Thoracic Society Committee on Dyspnea. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Feb 15;185(4):435-52. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. PMID: 22336677; PMCID: PMC5448624.

- Yorke J, Russell AM, Swigris J, Shuldham C, Haigh C, Rochnia N, Hoyle J, Jones PW. Assessment of dyspnea in asthma: validation of The Dyspnea-12. J Asthma. 2011 Aug;48(6):602-8. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.585412. Epub 2011 Jun 2. PMID: 21635136; PMCID: PMC3149863.

- Santus P, Radovanovic D, Saad M, Zilianti C, Coppola S, Chiumello DA, Pecchiari M. Acute dyspnea in the emergency department: a clinical review. Intern Emerg Med. 2023 Aug;18(5):1491-1507. doi: 10.1007/s11739-023-03322-8. Epub 2023 Jun 2. PMID: 37266791; PMCID: PMC10235852.

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.