In part one of this series on emergency front of neck access (eFONA), we unpacked some poor mindsets around the commitment to and placement of a tube in the front of a critically ill patient’s neck. The procedure is not benign, it is known to be dangerous and carries with it some real risk, but it is simple and straightforward.

In the last installment we highlighted that the most significant part of the procedure is making the decision to perform the procedure, and that waiting too long to do so reduces the chances of a meaningful outcome for the patient.1 In this installment we will show that eFONA has a PLACE and that while the situations surrounding the procedure can be charged and complex, that this complexity does not have to be passed on to the procedure itself.1

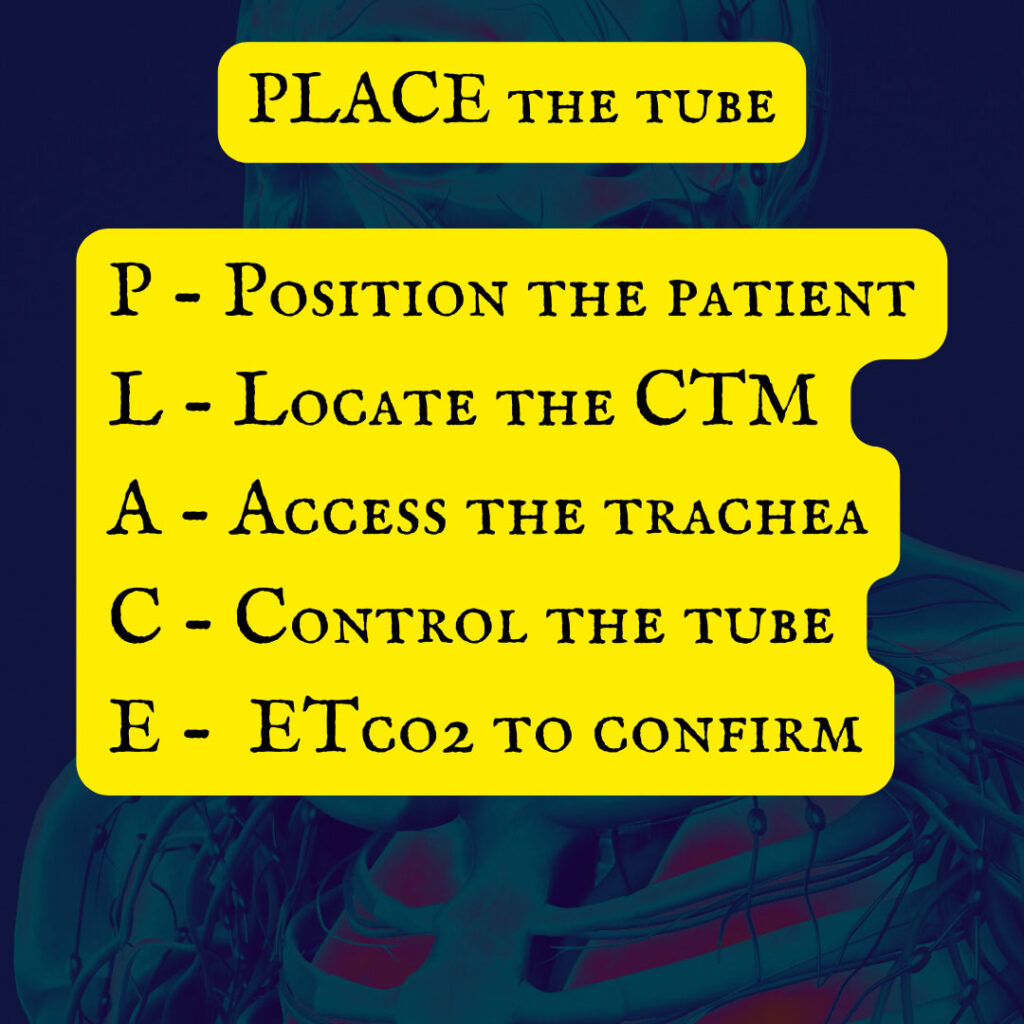

eFONA PLACEment

PLACE is an acronym developed by this author to cover the necessary steps for eFONA placement, and it is only that, an acronym for reference. This does not replace your local jurisdiction’s protocol or guidance for the execution of eFONA.

P – Position the Patient: As with any other airway procedure, properly positioning the patient is a key and essential first step. The cricothyroid membrane (CTM) is a small landmark and proper positioning can open the gaps in the tracheal rings and CTM, making it easier to palpate the area and feel the CTM.2 The caveat to this is that the CTM is not palpable on every patient; body habitus, tumors and other forms of anatomical disruption can make it difficult if not impossible to palpate the CTM. But this is not the only reason to position the patient well, however, opening the tracheal rings and the cricoid rings enlarges the space possible for the procedure.2 The position, as injury precautions allow, is hyperextension of the head and ensuring the head is midline.2

L – Locate the CTM: More importantly, locate the midline of the neck. This is most easily accomplished using the “kung fu grip” or “laryngeal handshake” where the operator grasps the larynx between the 2nd and 3rd digit and the thumb of the non-dominant hand.3 This leaves the index finger of the non-dominant hand free to palpate the CTM/find the midline of the neck.

This method is rather effective in locating the midline of the neck, then in those patients where it is possible, the operator can palpate the CTM and gather the last of their landmarks to begin accessing the trachea.

Revisiting the theme of being able to palpate the CTM. The ability to do so actually makes a significant difference in how the clinician will proceed with the procedure from this point. It also bears revisiting one of Dr. Levitan’s cricothyroidotomy mantras: “I will locate the CTM after the first incision…” In a patient like that pictured above, finding and palpating the CTM is straightforward and merely requires that the operator knows the landmarks and can confirm that they are in the correct place.

Once the patient presents with anatomical difficulties that make finding those landmarks problematic (e.g. obesity, tumors, trauma, etc.), a change in approach is necessary. In this case it becomes important to incise the front of the neck and find the CTM so that the operator can access the trachea.3 Once the neck is opened, along the midline, and in the estimated location of the CTM, the standard process of palpating the CTM to confirm location is advised and then the trachea can be accessed.

A – Access the Trachea: Once the CTM has been exposed/located, a simple puncture of the CTM is all that is required to facilitate placement of the tube. Puncturing the CTM is followed by a simple extension of the opening to the edges of the cricoid ring. It is often taught that a real risk associated with eFONA is the possibility of transecting a major blood vessel with horizontal extension of the opening.

While it is a risk, there are two very simple and easy ways to mitigate that risk. First, the cricoid cartilage forms what amounts to a bony cage that protects the posterior of the trachea and adjacent structures (to include blood vessels); and second, the operator must be in the correct place. With these two parameters are met, the risk is dramatically reduced that an important blood vessel will be transected.

At this point it is important to note that once a hole is made in the trachea, the operator must control it. The oldest… and most important adage of eFONA is to remember that once a hole is placed in the trachea, the operator is to keep something in that hole until the tube is secured with the balloon up.

This can be accomplished in a number of ways from inverting the blade and placing the back of the scalpel in the hole or using adjuncts like forceps or tracheal hooks. The danger of the adverse events increases exponentially if the operator loses sight of the opening.

C – Control the Tube: There is a dearth of resources and tried/true hacks to securing a tube so that it does not fall out of the trachea. Everything from oxygen tubing tied in a clever rope hitch to commercial “tube tamers” are available to prehospital clinicians to ensure that the tube stays in place.

But one item that lacks significant reinforcement is maintaining control of the tube during movement. Loading and unloading of the patient is one span of time that poses a significant risk to tube dislodgement. In this instance it is important that a single individual be designated as the “airway safety” who not only physically controls the tube with their hand, but verbally controls the movement of the patient.

Ventilator tubing gets hung up on steps, BVMs accidentally get disconnected, and people sometimes fall while trying to move into or out of a vehicle. Having a single individual in charge of all movement works to ensure the risk of dislodgement secondary to one of the aforementioned causes is mitigated to the greatest degree possible.

The other most dangerous time for patient movement is the transition between are teams, aka the patient handoff. This patient likely has more going on with them than just having a cricothyroidotomy placed, and there are many things that can draw the care team’s attention away from the tube. To that point, a similar approach of having a single designated individual in charge of patient movement is key. Add to it that this person should command the room and ensure that their voice (ideally the only one heard at the time) clearly conveys that there is a surgically placed airway in the front of the neck and that individual will direct all patient movement until the ED team can take over.

E – ETCo2 Confirmation: As with any advanced airway, ETCo2 remains the gold standard for confirmation of placement. Chest rise and Spo2 can be extra confirmatory steps (among a myriad of other options), but the qualitative waveform remains the mainstay standard of care for tube confirmation.

Conclusion

While eFONA may be anxiety provoking and wrought with risk, it does not have to be. Along with cognitive aids like the PLACE acronym, regular training and drilling will further reduce the risk of poor outcomes in eFONA. The mindsets around eFONA as a “failed airway” approach or “last resort only” can hinder operators on scene who may need to make a split second decision within a really tight time constraint. The PLACE acronym can help prehospital operators move through some of the stickier portions of eFONA despite some of the challenges to its operationalization.

References

- Bick E, Barnes J, Roberts J. Can’t intubate can’t oxygenate: It takes more than a patent airway to oxygenate a patient. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;37(6):503-504. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001143. PMID: 32379147.

- Law JA, Duggan LV, Asselin M, Baker P, Crosby E, Downey A, Hung OR, Kovacs G, Lemay F, Noppens R, Parotto M, Preston R, Sowers N, Sparrow K, Turkstra TP, Wong DT, Jones PM; Canadian Airway Focus Group. Canadian Airway Focus Group updated consensus-based recommendations for management of the difficult airway: part 2. Planning and implementing safe management of the patient with an anticipated difficult airway. Can J Anaesth. 2021 Sep;68(9):1405-1436. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02008-z. Epub 2021 Jun 8. PMID: 34105065; PMCID: PMC8186352.

- Law JA, Duggan LV, Asselin M, Baker P, Crosby E, Downey A, Hung OR, Jones PM, Lemay F, Noppens R, Parotto M, Preston R, Sowers N, Sparrow K, Turkstra TP, Wong DT, Kovacs G; Canadian Airway Focus Group. Canadian Airway Focus Group updated consensus-based recommendations for management of the difficult airway: part 1. Difficult airway management encountered in an unconscious patient. Can J Anaesth. 2021 Sep;68(9):1373-1404. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02007-0. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34143394; PMCID: PMC8212585.

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.