Introduction

Magill forceps, first described by Dr. Ivan Q. Magill in 1920, were initially utilized to help administer nasotracheal anesthesia.1 They were constructed with “a bend to clear the field of vision… the ends which grasp the catheter representing a cylinder split longitudinally and serrated on the inner surface.”2 Over time, the use of this tool has expanded to tracheal foreign body removal in the unconscious patient.

The frequency of choking has a bimodal distribution between pediatric and elderly patients; it is the leading cause of infantile death.3 In 2020, 3560 people died from choking, 71% of these patients were over the age of 65.4,5 Initial first aid for choking includes the abdominal thrusts and back blows for conscious adult patients.6 When these measures fail, advanced life support is initiated, including removal of the visualized foreign body by laryngoscopy, advanced airway management, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation if indicated.7

Current educational literature on the proper use of Magill forceps in the removal of foreign body is limited and conflicting. Few texts note the hand position and grip while using forceps, and even fewer have images to demonstrate the optimal technique. Our review of the current literature available to clinicians repeatedly revealed conflicting images, vague descriptions, and incomplete instructions. There is no definitive definition, policy, or protocol for the proper grip and technique for the use of Magill forceps.

Optimal use of Magill forceps is vital for efficient and effective foreign body removal. During simulated training at an ambulance service in northern New Jersey, paramedics and nurses who used Magill forceps with the identified optimal grip removed a tracheal foreign body faster than those who used an overhand, underhand or varied grip. As with any advanced life support (ALS) tool, there must be a universal protocol and technique for its use amongst ALS clinicians. In this article, we will draw attention to a gap in the current educational literature available to clinicians and outline a suggested standardized technique for the optimal use of Magill forceps. Our goal is to provide a stepping-stone for clinicians to assess their use of Magill forceps.

Current Information Available to Clinicians

One text, Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured, describes the indications for use of Magill forceps for foreign body removal.8 This text outlines proper patient positioning, direct visual laryngoscopy technique, visualization of the foreign body, insertion of Magill forceps, and removal of the debris. This is where many texts fall short: there is no description of the proper way to hold and use the forceps. The text has a photo demonstration of a clinician holding the forceps with the index finger and thumb, in an overhand manner. A later image in this chapter shows an image of an ALS clinician holding the forceps in what we describe as the “optimal method.”

Queensland Ambulance Service airway management protocols features a demonstration of a clinician holding the Magill forceps with the thumb and fourth finger, with a clear visual field.9 At this point, current literature has again fallen short. In another ALS educational resource, Magill forceps are listed as a tool to clear the airway with direct laryngoscopy, but no technique is described.10

Benumof and Hagberg’s Airway Management describes in great detail how to hold the forceps, a variation from previous literature available.11 Unfortunately, this description is for the use of Magill forceps for the advancement of a nasotracheal tube during nasotracheal intubation. The text notes, “As the forceps are grasped parallel to the long axis of the tube, a backhand motion of the right hand passes the ETT toward the glottic opening.” It is also possible that the technique of use for nasotracheal intubation may differ from that used for tracheal foreign body removal.

There are numerous scholarly articles citing the utility of Magill forceps for the removal of tracheal foreign body removal. One study, based in Osaka, Japan, found that the use of Magill forceps for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to foreign body obstruction was associated with neurologically favorable outcomes.12 Another study demonstrated that utilization of Magill forceps was successful in cases of foreign body aspiration refractory to the Heimlich maneuver.13 Additionally, there are several case reports where Magill forceps were used for near-complete foreign body airway obstruction with respiratory distress.14 None of these articles describe the technique used for holding and positioning the forceps.

Review of Techniques

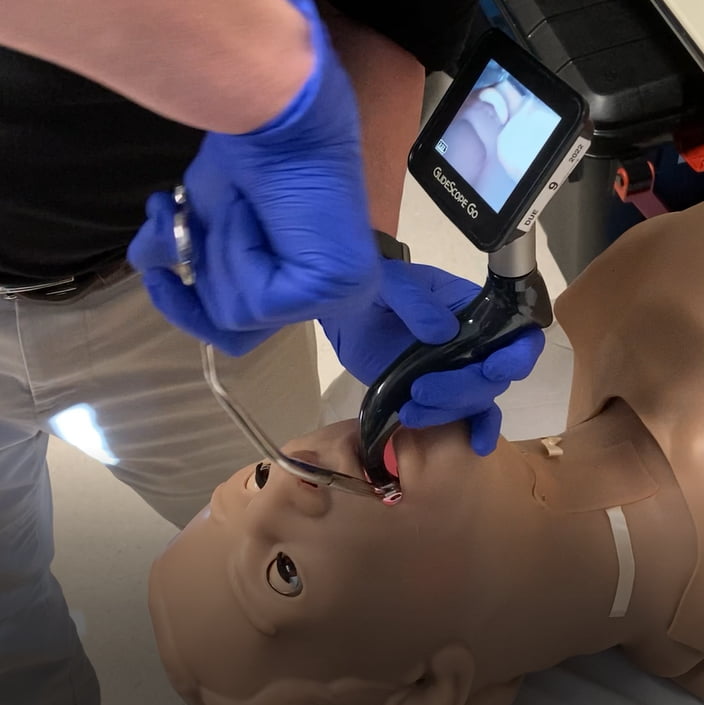

During an annual competency training session for paramedics and nurses (ALS clinicians), we observed significant variation in how the clinicians used the Magill forceps for airway foreign body removal. For this exercise, a standard foreign body was placed in the laryngeal opening of a mannequin, and clinicians were timed from laryngoscope insertion to time of foreign body removal. The initial intent of this exercise was to observe the difference in removal time between direct laryngoscopy and video laryngoscopy using the Glidescope Go; however, we observed that the most important factor determining speed of foreign body removal was clinician hand positioning. Seventy-six clinicians were timed from laryngoscope insertion past the incisors to foreign body removal. There were three common hand positions that were identified when our ALS clinicians attempted to remove a foreign body airway obstruction with Magill forceps. We stratified these techniques into four categories: optimal, overhand, underhand, and multiple positions.

- Optimal Method

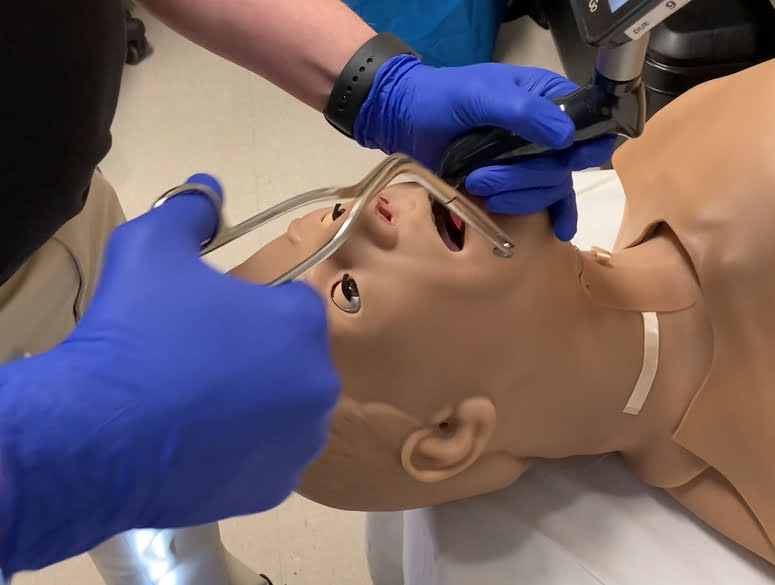

The first position used is denoted as the “optimal” method. A little more than half (37 out of 76) of the clinicians used this method. The forceps are grasped from with the right thumb and middle finger, with the right hand in a handshake position, and the angle of the forceps superior to the hand. This technique is demonstrated in figure 1. Average foreign body removal time with this technique was 12.4 seconds.

Figure 1: Optimal positioning of the Magill forceps for foreign body removal.

This positioning allows for horizontal orientation of the grasping end at the glottic opening, therefore minimizing the risk of damage to the epiglottis during removal. The field of vision is clear with the hand below the angle of the forceps. Additionally, the hand can be easily rotated 180 degrees, so that the grasping end can be oriented vertically if needed, without interference from the laryngoscope. Clinicians who used this hand position demonstrated the fastest foreign body removal times.

- Overhand Method

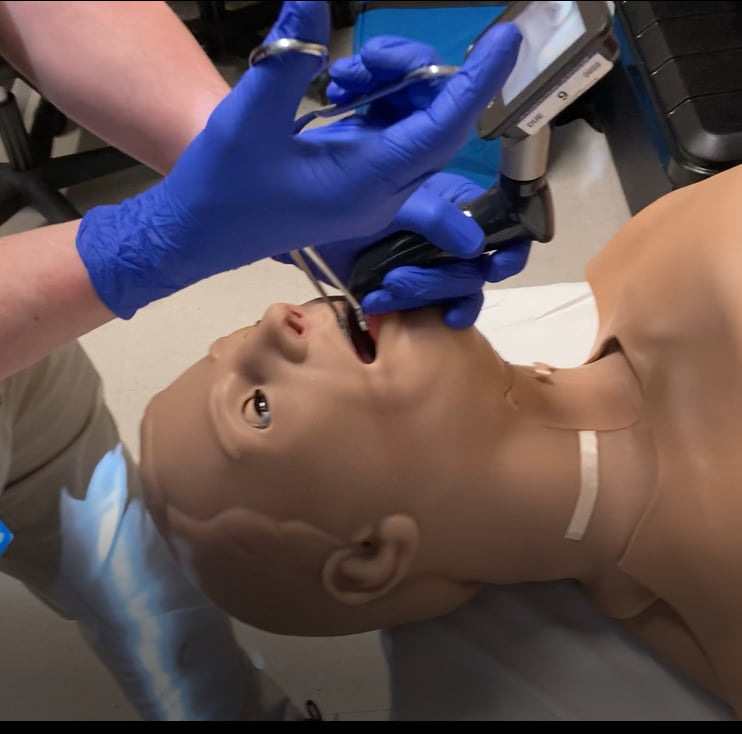

A common pre-conceived notion is that the angle of the forceps should be aligned with the natural curvature of the airway. However, this is incorrect, as the bend in the Magill forceps does not actually enter the airway. With this positioning, the angle does not assist with visualization or the extraction of the foreign body. Figure 2 provides a visualization of the “overhand method,” where the hand is superior to the angle of the forceps during extraction. Ten clinicians used this method. Here, the forceps are again grasped by the right thumb and middle finger, with the right hand in a handshake position, but the angle of the forceps is inferior to the hand. The average time for removal with this method was 17.3 seconds.

Figure 2: A demonstration of the “overhand method.”

This positioning causes the grasping end of the forceps to be positioned vertically within the airway. For foreign bodies in the hypopharynx, this method may yield success. However, if the foreign body is located near the glottic opening, there is a higher risk of epiglottis trauma during a removal attempt. Additionally, the range of rotation is limited to 90 degrees in this position, offering poor maneuverability. Rotating the forceps in a counterclockwise manner causes interference with the laryngoscope.

- Underhand Method

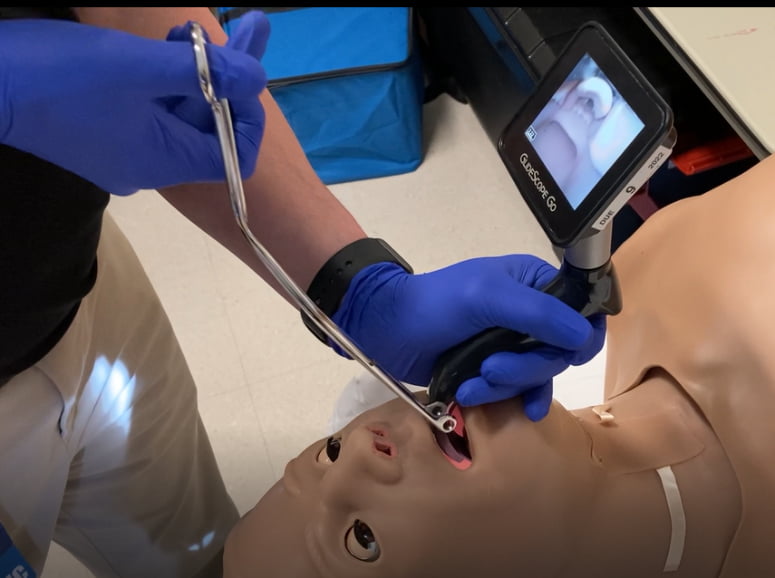

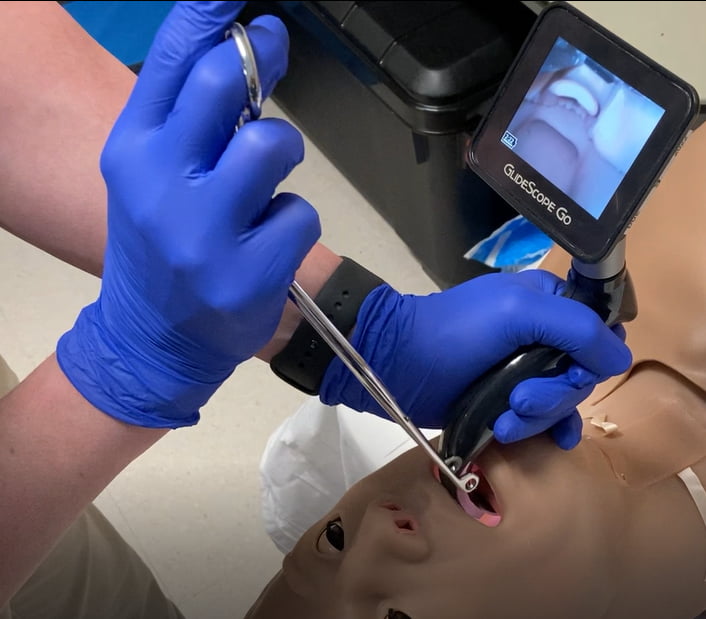

The final method noted also has the angle of the forceps inferior to the hand. In this case, the hand was in varied positions: supine, pronated, or flexed, as seen below. Each of these three positions used a similar backhanded wrist motion to insert the forceps, therefore they were grouped together and denoted as the “underhand method.” Figures 3, 4, and 5 each demonstrate the underhand method, with three variations of hand position. 18 clinicians used this method, with an average removal time of 21. 8 seconds.

Figure 3: Variation 1 of the “underhand method.”

Figure 4: Variation 2 of the “underhand method.”

Figure 5: Variation 3 of the “underhand method.”

In each of these positions, the grasping end of the forceps are oriented horizontally relative to the glottic opening. Still, the ability to rotate the forceps is impaired by the laryngoscope and rotation limits the field of vision, thus making this an inferior method for foreign body removal.

- Multiple Positions

The last group of hand positions in our cohort were clinicians who used multiple hand positions. 11 out of 76 clinicians used multiple hand positions. This group started using any of the above techniques but switched hand positions due to limited exposure and training in the use of Magill forceps. Many clinicians cited inexperience with Magill forceps and long length of time since they last used the forceps when reflecting on their hand positioning. Clinicians who used multiple techniques had an average removal time of 35.3 seconds.

Discussion

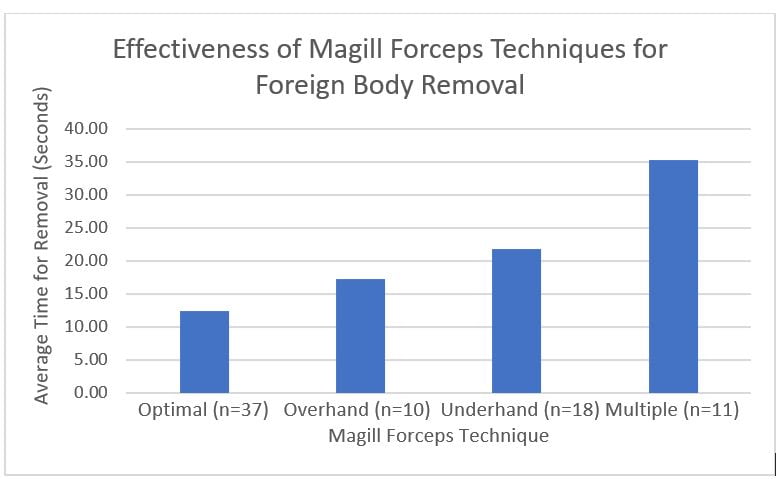

Our assessment has revealed that lack of education and clinical exposure amongst ALS clinicians resulted in numerous methods for using the Magill forceps. Figure 6 contains a table summarizing the average time for foreign body removal for each technique. This gap in skill proficiency resulted in a significant delay in foreign body airway removal for clinicians who did not utilize the “optimal” method. Properly training staff in the use of Magill forceps has the potential to impact patient outcomes and prevent further complications from foreign body aspiration.

Figure 6: A table depicting average time for foreign body removal for each different Magill forceps handling technique.

ALS clinicians, administrators, and educators must be aware of the confusion and lack of familiarity surrounding proper handling of Magill forceps amongst clinicians, prior to initiating educational measures. Using a standardized approach to education and skills assessment can ensure that all clinicians are using the most efficient method for airway foreign body removal. We urge EMS services to audit their internal protocols for training with Magill forceps and assess whether standardized education may benefit their clinicians. As a notable limitation, this review was conducted within one EMS agency and therefore may not be generalizable to all agencies. This review leaves opportunities for future researchers to investigate the use of Magill forceps in this context.

In summary, the superior hand positioning when using Magill forceps is grasping the handles with the right hand in a handshake position, with the angle of the forceps superior to the hand, demonstrated in figure 1. This technique allows for a better control of the forceps, without effecting the field of vision or the laryngoscope when rotating the grasping end. This review has highlighted the need to revisit how clinicians are educated on the use of Magill forceps. This infrequently used, life-saving tool is minimally discussed in initial paramedic education and largely forgotten throughout continuing education courses. Proper standardized education on how Magill forceps should be used will make clinicians more comfortable with using this tool, improve foreign body removal times, and decrease the likelihood of complications during airway foreign body removal.

References

- Nickson C. Magill forceps [Internet]. Australia: Life in the Fast Lane; 2022 Jan 18 [cited 2022 Feb 25]. Available from: https://litfl.com/magill-forceps/.

- Magill IQ. Appliances and Preparations. Br Med J. 1920;2:670. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3122.670

- Salih AM, Alfaki M, Alam-Elhuda DM. Airway foreign bodies: A critical review for a common pediatric emergency. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7(1):5-12.

- Injury Facts [Internet]. Itasca, IL: National Safety Council. 2020 Mar 8, Home and Community: Introduction; [cited 2022 Mar 20]. Available from: https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/home-and-community/home-and-community-overview/introduction/

- Duckett SA, Bartman M, Roten RA. Choking [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499941/

- American Red Cross: Basic life support: Participant’s Manual. Washington, DC: American Red Cross; 2021.

- Advanced cardiovascular life support provider manual. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2020.

- AAOS. Advanced Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured: Using Magill Forceps [Internet]. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2015 [cited 2022 Mar 20]. Available from: http://samples.jbpub.com/9780763779306/additionalSkills/Using%20Magill%20Forceps.pdf

- Clinical practice procedures [Internet]. Queensland, Australia: Queensland Ambulance Service; 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpp/CPP_Magill%20forceps.pdf.

- Direct Laryngoscopy & Magill forceps [Internet]. London, UK: St. John Ambulance; 2017 [cited 2022 Feb 25]. Available from: https://clinical.stjohnwa.com.au/clinical-skills/airway/direct-laryngoscopy.

- Hagberg CA, Artime CA, Aziz MF. Hagberg and Benumof’s Airway Management. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; c2013. Chapter 17: Laryngoscopic Orotracheal and Nasotracheal Intubation; p. 346-358.

- Sakai T, Kitamura T, Iwami T, et al. Effectiveness of Prehospital Magill forceps use for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to foreign body airway obstruction in Osaka City. Scand. J. Trauma, Resusc. Emerg.. 2014;22(1). doi:10.1186/s13049-014-0053-3

- Soroudi A, Shipp HE, Stepanski BM, et al. Adult foreign body airway obstruction in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007;11(1):25-29. doi:10.1080/10903120601023263

- Quiñones F, Saez M, Povatos EM, et al. Magill forceps. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11(5):302-303. doi:10.1097/00006565-199510000-00010

Coco Thomas, BSN, RN, EMT-B, is a medical student at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. She is a former adult and pediatric emergency room nurse and EMT, pursuing a career in emergency medicine.

Michael Berkenbush, MD, NRP, is an EMS Fellow and emergency physician at Atlantic Health - Morristown Medical Center in New Jersey. He is also a currently practicing paramedic, beginning his EMS and medical career as a volunteer EMT/firefighter, and subsequently has served as a paramedic in northern New Jersey and the Hudson Valley region of New York state.

Raymond Dwyer III, BS, MICP, is the assistant manager of Clinical and Quality for Atlantic Mobile Health. He brings 28 years of EMS experience, with 24 years as a paramedic and an educator.

Scott E Kansky, BS, FP-C, MICP, is the accreditation coordinator for Atlantic Mobile Health. He brings 30 years of experience as a paramedic and 15 years as a flight paramedic.

Thank you CoCo for this study!!! I have been trying to teach the “optimal” method to EMS, Flight, CRNA and physicians for years. The discuss and photos will be super helpful in future courses. Please send me an email, I would like to share with you why the McGills were designed they way they are – it was not mentioned in your study. [email protected]