Event coverages are among some of the greatest duties a prehospital team can perform. Sometimes we meet the celebrities or fighters; get a cool photo opportunity for our social media; and it is some easy overtime. Tonight, we have an MMA fight to watch.

As the main event kicks off the two gladiators circle each other and soon the fight is on. After a moment or two of grappling and rolling, one of the fighters (Blue Shorts) finds themselves in the precarious position of a deep guillotine choke.

As if the position could not be any more uncomfortable, Blue Shorts feels the ankles of his opponent lock together at the small of his back and an incredible pain in his head and neck. Just as it feels like his head is going to separate from the top of his neck there is a “crunch” sensation in his throat, and it soon feels like something is stuck in his throat.

Blue Shorts taps his opponent frantically in a way that not only signifies that the fight is over, but that something is really wrong. He is left in the middle of octagon on his hands and knees with one hand on his neck. We notice that he appears to be giving the universal sign of choking.

When we get to him in the ring, he turns over to sit in a tripod position. He is coughing and in obvious respiratory distress clutching at his neck. “I can’t breathe!” is what he is able to whisper in a raspy hoarse voice with maximal effort.

We look around and find his mouthpiece on the mat, which rules that out as an obstruction. A quick look into his mouth reveals that all of his teeth are in place and his tongue is in one piece. Soon he begins to flail in the panicked fashion that signifies an extreme level of distress.

What has befallen Blue Shorts?

Tracheobronchial Tree Injuries

All images created by the author.

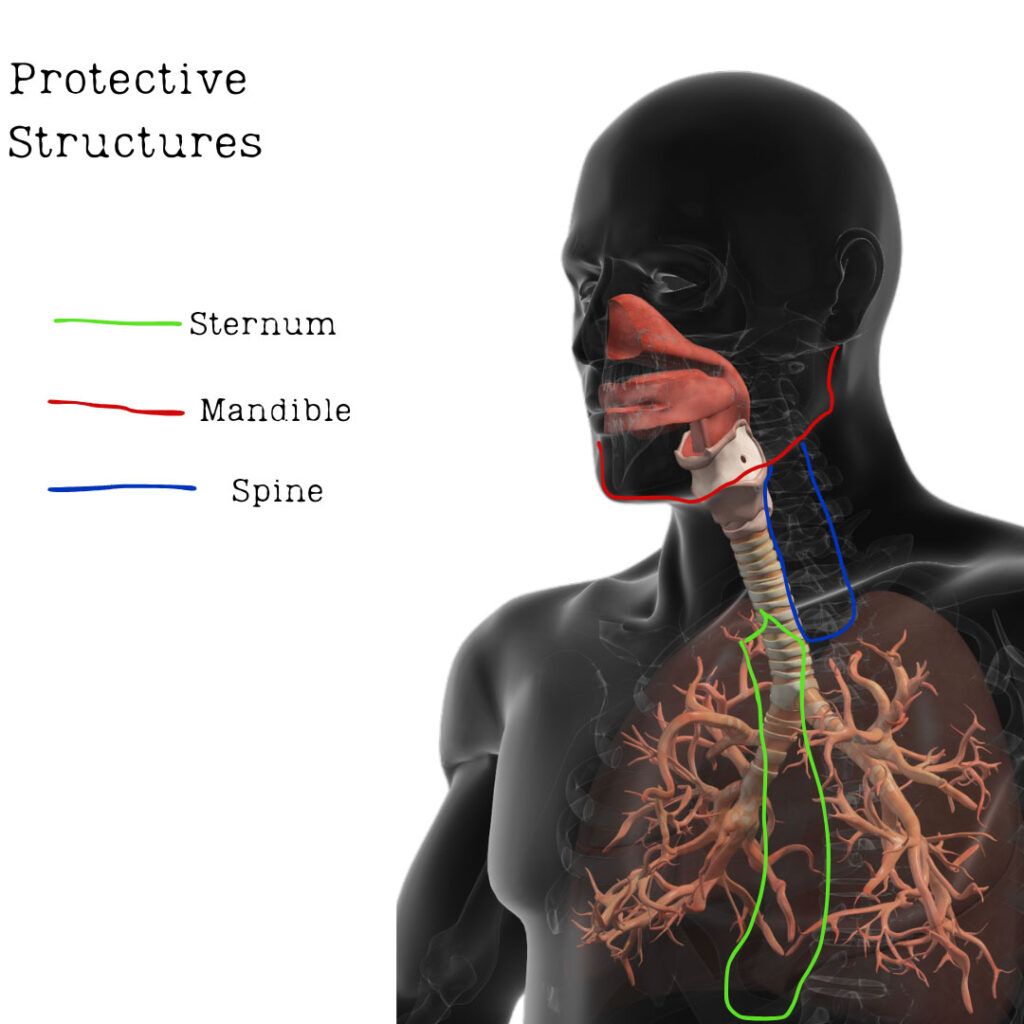

Injury to the trachea is rather rare with an incidence of 1:30,000 cases, but it is the second most common cause of death in patients with head/neck trauma.1 It is well protected by the spine, mandible, and the sternum which likely accounts for the low incidence of injury to the trachea.1

When it does happen, it represents a loss of airway patency that can be rapidly fatal if unrecognized and corrected. Injury to the tracheobronchial tree or the cervical trachea is associated with a 1%-11% mortality rate, and those which transect the trachea completely are usually fatal.2

Identifying laryngeal trauma is relatively straightforward. Of course, this starts with a mechanism of injury that suggests trauma to the larynx. Penetrating trauma to the neck should create a high index of suspicion for laryngeal involvement. Blunt trauma can be a little more cryptic in the presentation of laryngeal trauma or tracheobronchial tree injury. Direct impact to the neck or crushing forces (like hanging or strangulation) should prompt the prehospital clinician to dig deeper and ensure that the trachea is intact.

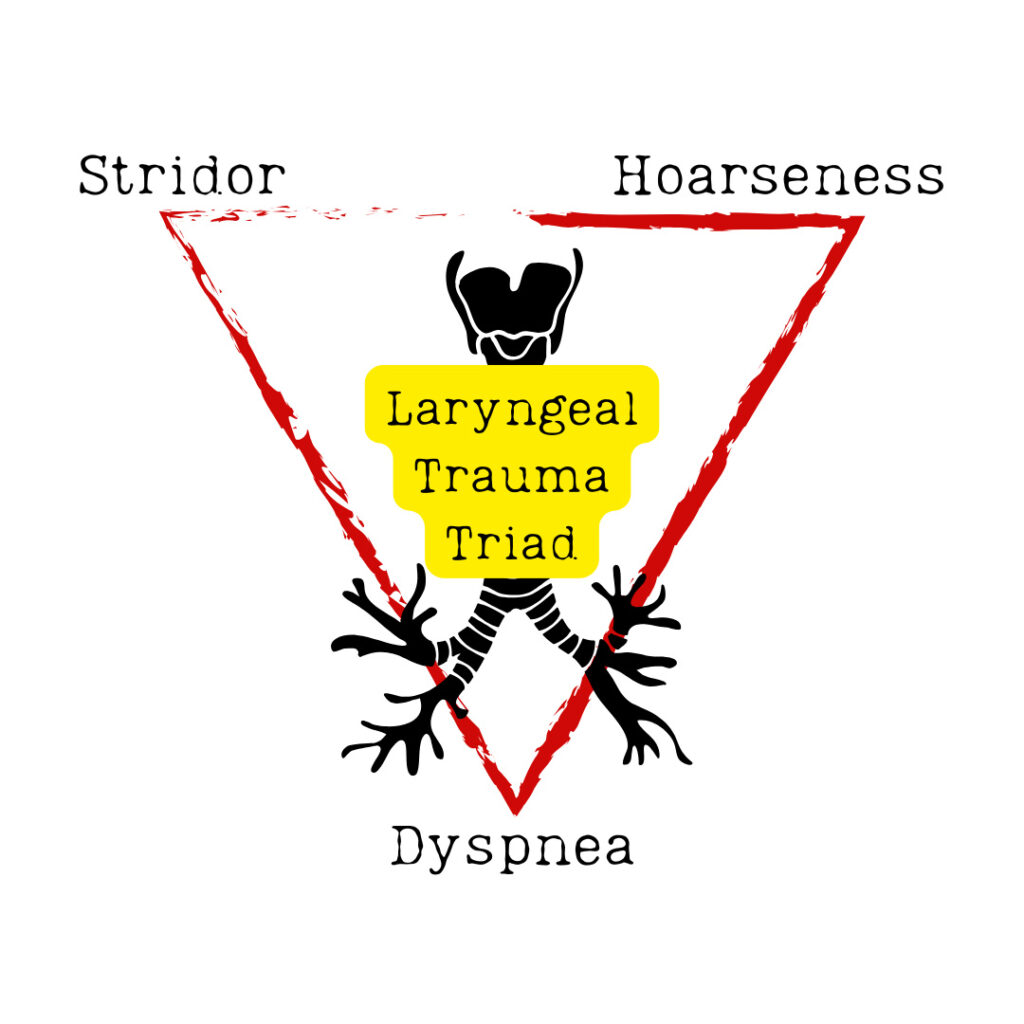

A concerning mechanism with other signs like stridor, hoarseness, and dyspnea (aka the laryngeal trauma triad) raises the index of suspicion for laryngeal injury even further.2 Other signs to look for, but are less specific, are dysphonia, neck pain, and hemoptysis.2

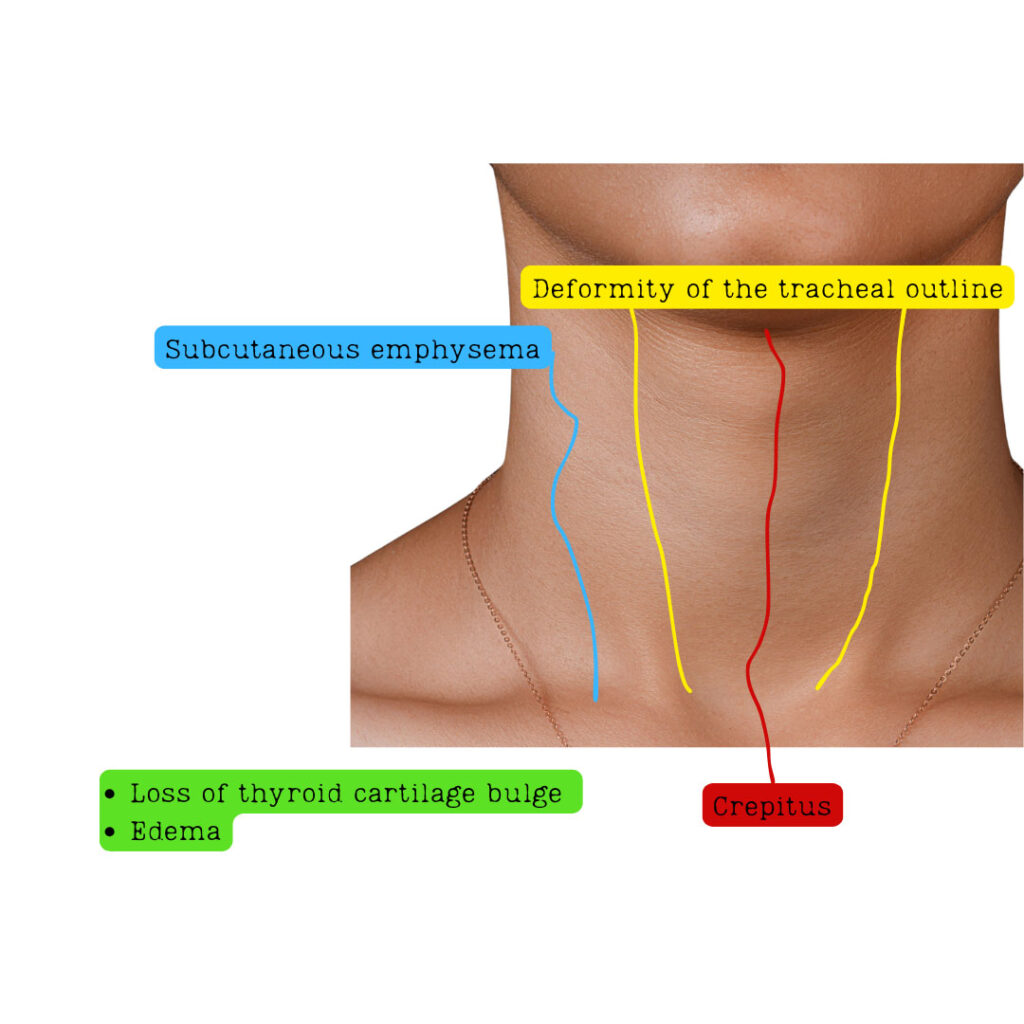

Physical exam findings consistent with this injury are a deformity of the tracheal outline, loss of the thyroid cartilage bulge, subcutaneous emphysema, tenderness, and crepitus across the front of the neck. When there is an injury to the tracheobronchial tree it is common to encounter subcutaneous emphysema and signs of a pneumothorax.2

While bronchoscopy is next to impossible to perform in the prehospital setting, there is a novel approach of using point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to assess for airway trauma.5-6 POCUS airway assessment in this case can reveal a displaced thyroid cartilage fracture, cricoid cartilage fracture, or airway edema.5

This assessment can take place either pre or post-intubation. Data on its use for the identification of laryngeal trauma is sparce and mostly limited to case-reviews, however, the application of it in this setting still seems reasonable and without demonstrable harm to the patient.

It is not a foolproof tool, it can be obscured by the presence of subcutaneous emphysema, cartilage calcification, and foreign bodies. These issues can result in artifact that can obscure injuries.5 POCUS can also be useful in confirmation of tube placement beyond the point of the injury.5

Airway Management

Direct trauma to the tracheal anatomy can create a rather difficult situation for even the most experienced operator. This is an “intubate, now” situation due to a loss of integrity of the airway passage. Supraglottic airway (SGA) devices may prove to be ineffective in some cases due to the need to seal and secure the trachea past the point of the injury.

This would look like worsening subcutaneous emphysema post SGA placement with positive pressure ventilation. SGA placement will also fail to support any collapse of the tracheal structure.

Intubation may still fail to secure the airway if it is placed superior to the injury, which would still facilitate significant air leak into the subcutaneous tissue or thoracic cavity. It can also fail if the injury is such that the endotracheal tube cannot pass beyond the injury or if it results in a passage outside of the trachea, creating a false lumen the tube passes into.

If intubation is not possible, placing a surgical airway may be necessary. In penetrating trauma with tracheal involvement, there are several case reviews and other literature that support passage of the tube through the wound if normal landmarks cannot be appreciated.2-4 In the setting of blunt traumatic injury to the trachea, surgical airway via the standard front of neck access method is recommended.2-4

A common treatment modality, especially when the location of the injury is known, is to advance the tube past the point of the injury. If the location of the injury is not known, then it may be necessary to perform a right-mainstem intubation.2-4

This ensures that oxygenation and ventilation can still occur and sustain the patient until surgical correction. This method is not without pitfalls and concerns of hypercapnia and acute lung injury in the ventilated lung.

No Trace, Wrong Place

ETCO2 may be the first or only indicator that there is tracheal damage post intubation. While these injuries are commonly missed in the emergency phase, intubation may still occur and it may be only after the tube is placed that problems arise.

ETC02 is also beneficial for evaluating the effective placement of the ET tube in the presence of laryngeal trauma. Signs of poor ventilation post intubation may be an indicator that the tube is above the site of the injury and significant leak is present.

The PUMA group provide guidance on what an appropriate waveform will look like on the monitor:7

- Amplitude rises and falls with exhalation and inhalation

- Consistent or increasing amplitude over at least 7 breaths

- Peak amplitude at least 7.5mmHg above baseline

- Reading is clinically appropriate

Tracheal disruption will appear like massive air leak on a capnogram. The amplitude may be variable and inconsistent, suggesting poor air movement. The appearance of the wave form will be missing the characteristic 4 phase appearance, instead appearing more pointed (like a birthday party hat).8

Conclusion

While rare, laryngeal trauma and disrupted tracheas can be lethal. Many of these patients die before reaching the hospital, if the injury is not identified. The mechanism of injury and physical exam findings should paint a picture that the airway is not patent.

If not, listen for persistent dry coughing, hemoptysis, and aphonia. A pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema, while not specific to laryngeal trauma, warrant a deeper assessment of the trachea to ensure it is not fractured.

References

1. Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018 Mar;7(2):210-216. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.03.03. PMID: 29707498; PMCID: PMC5900084.

2. Herrera MA, Tintinago LF, Victoria Morales W, et al. Damage control of laryngotracheal trauma: the golden day. Colomb Med (Cali). 2020 Dec 30;51(4):e4124599. doi: 10.25100/cm.v51i4.4422.4599. PMID: 33795902; PMCID: PMC7968428.

3. Grewal HS, Dangayach NS, Ahmad U, et al. Treatment of Tracheobronchial Injuries: A Contemporary Review. Chest. 2019 Mar;155(3):595-604. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.018. Epub 2018 Jul 27. PMID: 30059680; PMCID: PMC6435900.

4. Rossbach MM, Johnson SB, Gomez MA, Sako EY, Miller OL, Calhoon JH. Management of major tracheobronchial injuries: a 28-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998 Jan;65(1):182-6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01001-1. PMID: 9456114.

5. Adi O, Sum KM, Ahmad AH, Wahab MA, Neri L, Panebianco N. Novel role of focused airway ultrasound in early airway assessment of suspected laryngeal trauma. Ultrasound J. 2020 Aug 12;12(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00186-3. PMID: 32783133; PMCID: PMC7419387.

6. Osman A, Sum KM. Role of upper airway ultrasound in airway management. J Intensive Care. 2016 Aug 15;4:52. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0174-z. PMID: 27529028; PMCID: PMC4983796.

7. Chrimes N, Higgs A, Hagberg CA,et al. Preventing unrecognised oesophageal intubation: a consensus guideline from the Project for Universal Management of Airways and international airway societies. Anaesthesia. 2022 Dec;77(12):1395-1415. doi: 10.1111/anae.15817. Epub 2022 Aug 17. PMID: 35977431; PMCID: PMC9804892.

8. Owen Hibberd, Niamh Beirne, Dani Hall . A Beginner’s Guide to Capnography, Don’t Forget the Bubbles, 2022. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31440/DFTB.50639

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.