If one were to peruse the available airway management literature as they attempt to build a good airway management program, they would find themselves with a dearth of tools, tips and tricks. Some of which have great evidentiary support while others may have questionable or less than high-level evidence supporting its use.

The trick, in the author’s opinion, is not to attempt to find a silver bullet one-size fits all approach; but to build an adaptable size fits most system to address the airway management needs of the patient.

Building that system can be as simple or as complicated as the operator wants it to be. Of course, the recommendation would be to simplify it to the greatest degree possible, and that simplicity is key. To paraphrase Stanley McChrystal, when we attempt to introduce a complicated solution to a complex problem we create chaos. Chaos in airway management may cause more harm than good.

Resuscitation and the Mind

Where does the chaos come from? Why is it seemingly so difficult to just marshal our resources and get it done? Stress and the human brain do not come together well in situations that require precision and a clear mind. The dramatic interplay of the situational context, our feelings and the gravity of the patient’s condition creates a storm of emotion.

That storm works to hijack our limbic system. We call it the “fight or flight” response. The result of this hijack is the appraisal of a situation as “bad” or “good.” More accurately this is described in the literature as the “threat, challenge” appraisal.1

The assessment of “bad” or “threat” coupled with an appraisal of our ability to meet the challenge is where the stress comes from.2 That stress inhibits or handicaps even the most capable clinician’s cognitive maps and workflows.1

This is not an insurmountable problem. We merely need to train more, right? Wrong. Training alone will not fix this problem, because it is beyond influencing psychomotor abilities.2 It attacks our cognitive abilities as well.

For that we need a different approach. Checklists, breathing exercises, etc., are all elements of a response system that can work to defeat the limbic hijack and allow for higher level execution.2 How? It allows us to influence what Daniel Kahneman identified as System 1 and System 2 thinking.3

System 1 and System 2 thinking is a way to conceptualize how the human brain sorts through information and develops an action or response to a stimulus. We can use either the fast system or the slow system, and that depends on how well trained and rehearsed the response is prior to the incident.3

System 1 is the fast system, characterized by how automatic or ingrained the response is to a certain stimulus.3 System 2 on the other hand is a little slower and analytical. It requires more brain power and mental bandwidth to process the information and arrive at a response.3

The trick behind using a system or a checklist is that it pushes System 2 information over to the System 1 side. It is written down with pre-planned responses, ergo we do need to use up brain power thinking about what needs to happen next.3

Back to the building of an airway management specific system. How can we take all these airway management tools and systemize them into an operational process?

PACE –Primary Alternate Contingency Emergency

PACE planning is a framework for organizing and prioritizing responses to known contingencies. It stands for Primary, Alternate, Contingency and Emergency. It was originally developed by U.S. Special Operations Forces to build in responses to failures behind enemy lines so that the operators would still be able to continue with the mission while maintaining functionality and combat effectiveness.

When applied in the context of airway management, it allows for responses to reasonable if/then scenarios in which clinicians plan for things to go wrong during management of the airway.

PACE is not something that can be done in the heat of the moment and to attempt to do so would be to invite disaster. Developing a PACE plan is part of the pre-planning process that is most effective when completed early and the various responses are rehearsed and discussed regularly. Each contingency should be simple enough to fit on quick reference cards that can be carried in a pocket for quick and easy retrieval.

P – Primary

This is “Plan A” and the most routine, uncomplicated way to approach a task. This is the way we want things to go and what we believe will be most successful first pass approach.

A – Alternate

This is where we begin to play if/then games. “IF this goes wrong or doesn’t work, THEN I will switch to this.” The alternate plan is the quintessential “Plan B” our back up plan. It is still a relatively routine way to accomplish the task, but we may have to modify one or two elements to be successful.

C – Contingency

The contingency plan is more of a “bailout” plan. We have already moved through our first two approaches and are still encountering variable that are forcing us to change things. For example, if the Primary and Alternate plans were to intubate the patient, but we could not mitigate the difficulty in the primary or alternate plan, then we may elect to abandon that approach altogether and place a supraglottic airway instead. It is easy to get into the weeds and develop several contingency plans, but the caution is to not make the plan so complicated that you create more and more chaos as you work through it.

E – Emergency

Things have gotten worse by this point. The emergency plan in airway management does not always have to be the surgical airway, however, it does need to be an approach that will not fail to establish a patent airway and ventilate the patient. The emergency plan must be a fail-safe parachute that will get you and the patient back to safe spot from which to move forward.

How Does This Help Me?

What does PACE planning do for a clinician? It allows the team to plan for things to go wrong and keep a positive mindset when they do. The inherent nature of the prehospital environment all but guarantees that there will be some variable that will foil a half-hearted attempt at anything. But a well-reasoned plan may potentially overcome that variable. It is about engineering resilience.

Both your mental resilience and procedural resilience. Resilience is the key in these situations as there is a psychological factor to effective resuscitation performance. Moreover, when things do not go according to plan, the team already knows how to respond and what is coming next because this was taken care of in the pre-planning phase. It can, if drilled and rehearsed enough, eliminate the “what do I do now” moments in between failed approaches.

What Does It Look Like?

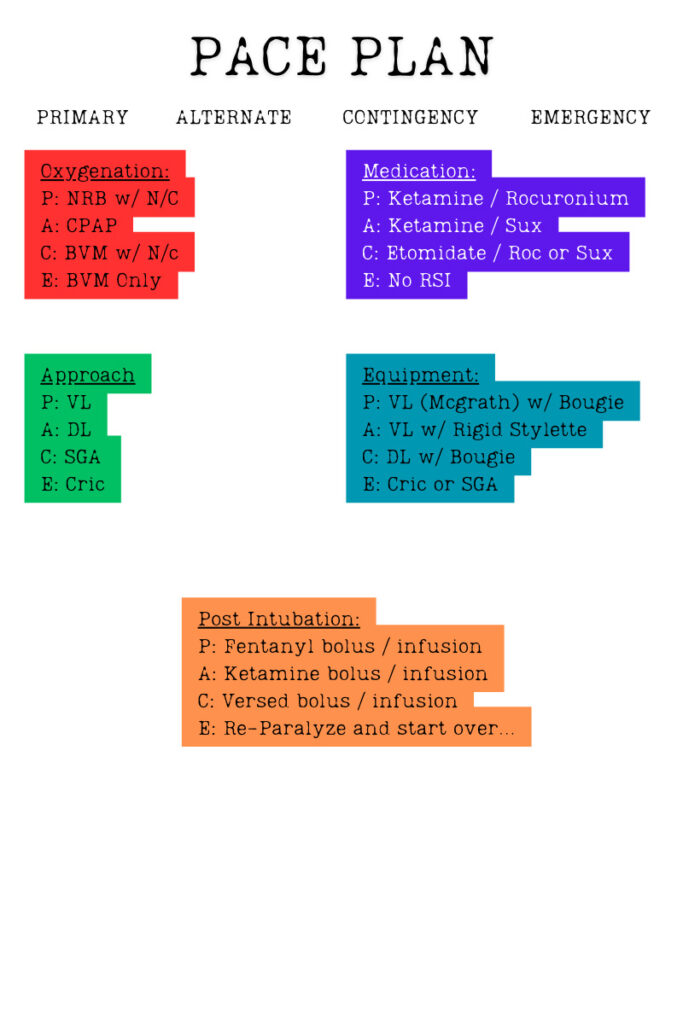

Below is an example of what a PACE plan for airway management could look like. It takes each phase of an airway management situation and then outlines each contingency by priority. It is somewhat dated, but the thought process is the example we are trying to highlight.

The PACE Plan. (Image created by the author.)

To Close Out

Failing to plan is planning to fail. Which is another mindset we borrowed from the military. Success in airway management cannot be left to chance or to luck. But, an operator can create their own luck with a well thought out PACE plan to help mitigate the variables that can precipitate an airway management disaster. Keep the plans simple and not overly complicated so as not to create more chaos than is already facing the team.

At the end of all of this planning is the key to success, procedural and mental resilience. PACE allows the operator to maintain a positive mindset and “fail-forward” through a plan without getting caught in a negative, defeated mindset over variables which they had no control over.

Plan, prepare. PACE yourself.

References

- Kovacs, G. & Law, J.A. (2012). Airway management in emergencies. Langara College

- Lauria MJ1, Gallo IA2, Rush S3, Brooks J4, Spiegel R5, Weingart S. Psychological Skills to Improve Emergency Care Providers’ Performance Under Stress. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Apr 28. pii: S0196-0644(17)30314-1.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin.

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.