Photos provided by the author.

Parker County (TX) Hospital District Emergency Medical Service (PCHD EMS), in coordination with medical direction by BEST EMS, strives for excellence in all aspects of patient care. We have recently deployed blood products, EPOC field lab testing, Hamilton T1 ventilators and body worn cameras (BWC). While the state-of-the-art equipment brings excitement and optimizes our patient diagnostics and treatment, we consistently evaluate data to determine areas on which we can improve.

After reviewing the data, PCHD EMS determined that one of the procedures that we needed to improve on and establish new goals for was advanced airway management, specifically resuscitation sequence intubation (RSI) as defined by the use of a paralytic for airway management.

At PCHD EMS, we adopted the use of Dr. Richard Levitan’s Resuscitation Sequence Intubation, to highlight the need to optimize all patients prior to endotracheal tube placement, and not just the rapid placement of an endotracheal tube.1

An area of research by Thomas, et al. showed is an area of concern for EMS agencies, “Overall, the intubation success rate was 78.8%, and the first-pass success rate was 68.5%.” For the years 2022 and 2023, we have been able to maintain first pass success rates greater than 96%. This improvement was a result of not only the engagement by our field staff, but through a group of dedicated educators.

While experimenting with many varied approaches, we settled into a model that produced the results we had previously established. The approach may not fit every service, but the great thing about education is that it is modifiable to suit any agencies needs and resources. The results of our trial-and-error approach resulted in the 7 E’s of Advanced Airway Management Education.

By implementing this approach, we have produced an improvement in our first pass success rates and continue to strive toward a 100% success rate while optimizing pre and post procedure patient outcomes.

PCHD RSI Success Rates

| Year | # of attempts | FPS | Percentage |

| 2017 | 24 | 20 | 83% |

| 2018 | 45 | 36 | 80% |

| 2019 | 59 | 55 | 93% |

| 2020 | 92 | 79 | 86% |

| 2021 | 86 | 74 | 86% |

| 2022 | 89 | 85 | 96% |

| 2023 | 128 | 124 | 96.88% |

Evaluation

A thorough and accurate evaluation is the foundation of an advanced airway management education system. Any service must take a factual account of their status, deficits and what they excel at. If a foundation is not in place, you cannot start to build a program.

At PCHD EMS, we use a variety of resources to evaluate our procedure’s effectiveness. We use ESO charting software to calculate our Dash-1A scores and first pass success rates. Body cam videos allow us to evaluate that what we are teaching is being put into practice. We consistently ask ourselves, “Is there a method to our teaching that needs to be adapted whether that is our approach or resources?”

Constant encouragement of honest feedback allows us to evaluate the instructors and delivery of the education. Evaluation is an ongoing process, not unlike you would see in any educational institution. We implement post course evaluations but have found that a better gauge of success is gained from conversation and review of the results.

By monthly evaluating our FPS, Dash-1A, and body cam video, we obtain a picture of the education process. We have found that simply evaluating the procedures being performed does not reveal the whole picture. The most difficult aspect is trying to identify patients that would meet the criteria for an advanced airway procedure but that was not performed.

Implementing varying criteria for chart review helps, but unless you implement 100% review, charts will slip through the cracks. Data shows that our medics that intubate the most frequently have higher overall FPS as opposed to those who intubate less. Which is in line with recent research, “Higher agency rates of intubation attempts were associated with increased rates of intubation success and first-pass success.”2

In the evaluation process, we learn more about the effectiveness of our program from reviewing those individuals who intubate very rarely or not at all. The odds of never having an intubation attempt over a long period of time, even with a small call volume, are extremely low. This is an area that we focus our evaluation on by asking questions. Why is this happening?

Are these individuals extremely lucky in the fact that they do not encounter severe respiratory patients, rarely is that the case. Are they aggressive with their initial treatments and avoid having to perform the RSI procedure? If so, we must evaluate the adjuncts being performed with patient long-term outcomes in mind. Are the providers less experienced or other factors that they trend back to the diesel bolus mindset.

Regardless of the circumstance, we explore how our educators can better tailor education, whether as a whole or individually. The evaluation process is more successful when not only successes and failures are considered, but also areas that lie outside the normal indicators. In the case of advanced airway management, that is usually a lack of attempts over a period relevant to the call volume. Evaluation is an ongoing and varied process that we constantly monitor to identify trends that help to optimize our educational experiences.

Evidence

EMS has embraced the idea that we operate different than Emergency Departments (ED), therefore emergency medicine has two different standards. At PCHD EMS and BEST EMS, we disagree with this. EMS providers will always have different factors that are not present in the ED due to multiple factors such as: space, location, or finances. This is not an excuse to ignore the fact that we are healthcare professionals and must practice evidence-based care.

Everything that we do at PCHD EMS is based on current medical evidence, whether it is published studies or anecdotal evidence we gathered based on our available resources. Everything that is patient care oriented is absolutely based on medical evidence and is evaluated by multiple physicians through BEST EMS before it is applied to the protocols.3

As new evidence regarding the RSI procedure becomes available, we make modifications to our RSI procedure for the benefit of the patient. This is apparent in our medical protocols and our RSI check list posted in all ambulances. We are major advocates for the use of checklist, especially in a high-risk procedure. “Human error is inevitable—particularly under stressful conditions…levels of cognitive function are compromised as stress and fatigue levels increase…This can lead to increased errors in judgment, decreased compliance with standard procedures, and decreased proficiency…An important tool in error management across all of these fields is the checklist, a key instrument in reducing the risk of costly mistakes and improving overall outcomes.”4

We also partner with UNT Health Science Center – School of Public Health to engage in research related to various EMS topics. We are strong believers in not only incorporating available evidence into practice, but also being part of the discussion and research itself. Clinical evidence must support any changes that we make regarding our RSI process. While changes may come slow, using group discussions and personal investigation, we attempt to be at the forefront of any avenue that can improve our education system or our practice of medicine. In coordination with the evaluation process, evidence can guide the education process.

Engagement

It is vital to have engagement from the very top down in our organization. At PCHD EMS, the first level of engagement starts with the management team and their approach of “How can we help and what do you need?” The cooperation at the management levels simply makes every aspect of the educational approach easier.

The second level of engagement that we have noted is the involvement of our medical directors at BEST EMS. Our medical directors are willing to engage in all aspects of the EMS operation. They provide in person education to our field staff, elicit provider input on any protocol changes, and are readily available for the casual hallway-type discussion.

We can achieve this direct communication and understanding with medical direction, in no small part, due to the fact that they are out in the field running calls with our medics two days a week. Our third level of engagement is between our educators and field staff. The individuals that provide our airway education are also critical care paramedics that work the same schedule as our medics. It provides many of the same benefits as the medical directors, but also allows the educators to practice what they preach.

Field staff witness the skills and knowledge of the educators in real life practice, which builds confidence in the learning environment that the educators can apply lessons to practice. The third level of engagement that we utilize is with the first responder organizations (FROs). PCHD EMS is the only ambulance service in the county, while the FROs provide fire, rescue, and assist with medical care of patients.5

The size of our county means that often FROs are on scene prior to the ambulance so, through hands on education, they can begin the optimization of patients prior to the arrival of the ambulance. The FROs build the foundational principles that the paramedics can work from for advanced airway management.

An added benefit is that the FROs know what we are doing and become a valuable resource on scene. In a critically ill patient, whether it is respiratory in origin or not, the more hands you have available the better you can manage patient care. We strive to implement a basic understanding of the RSI procedure, so that FROs are viewed as an asset on scene. With proper engagement, any procedure can be optimized through teamwork.

Equipment

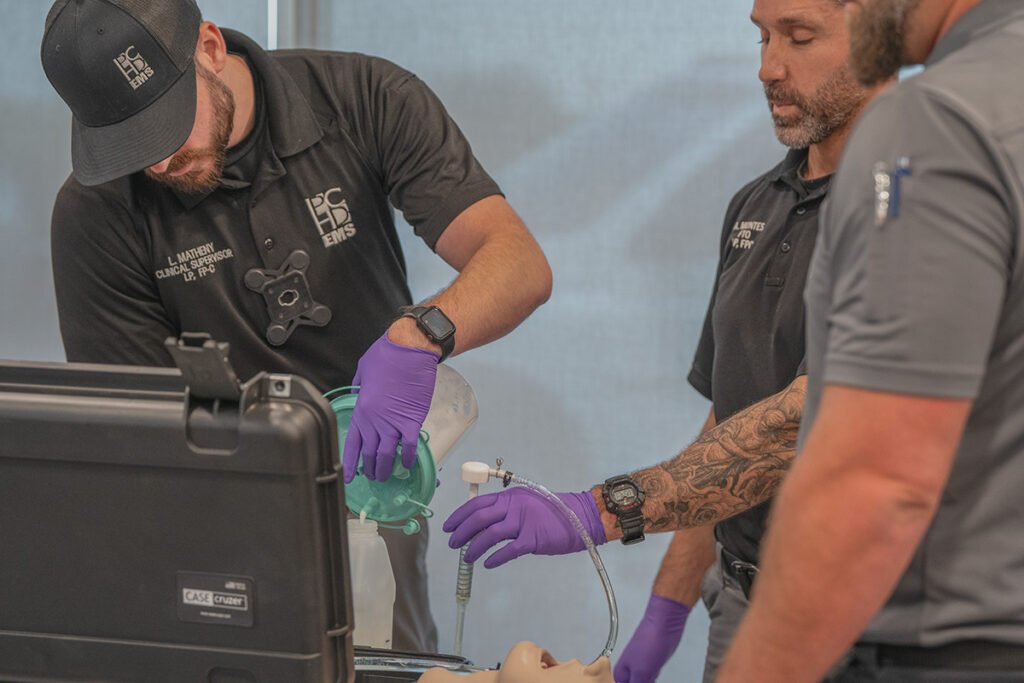

PCHD EMS divides equipment into two categories: equipment available on the ambulance and training equipment. We have found that it is of the upmost importance to combine these two categories to produce the most realistic training simulations possible. “Simulation training is an effective educational modality, with strong evidence demonstrating improvement in learners’ knowledge, skills, and behaviors and simulation approaches have been shown to improve patient-level outcomes.”6

We strive to create a realistic as possible approach to education that implements equipment that is used on an everyday basis. PCHD EMS is fortunate enough to, budget permitting, have the ability to continue to add new equipment regularly. Our experience is that when we replace equipment with a more advanced model or add altogether new equipment, field staff are eager to advance their proficiency. The excitement created allows our educators an opportunity to reinforce and highlight the patient optimization while incorporating new equipment in training.

By utilizing the advent of adding new equipment we can gauge the understanding of the staff on the entire process, without it being a dedicated class for advanced airway management. A recent example would be the addition of the Hamilton T1 ventilators on all in service units. The training scenarios are crafted to start from initial patient encounters thru intubation and placement on the ventilator. The trainee will encounter a post intubation issue that will require continued optimization.

Examples of such include a high-pressure alarm on an asthmatic patient or a post-ROSC tension pneumothorax. This allows our educators to highlight the continued need to optimize oxygenation and ventilation while making a connection to the pre-optimization before an intubation attempt. Instead of focusing a training opportunity on a single addition, we make connections that lead back to the basics of optimization.

Regarding specific training equipment, we have found that it is received by our staff with excitement when we can add more interactive training modules. The addition of the SALAD manikin allows us to give a realistic situation that better prepares our staff and creates more engagement by the students.

The two most valuable pieces of equipment that we utilize for informal training are the iSimulate and basic airway manikins at each station. The iSimulate allows our medics to make a connection while running scenarios with the most widely used piece of equipment in our department, the LifePak 15.

It adds an element of realism, as when the medics are applying treatments in a scenario the educators can change the capnography waveform, lower the heart rate, increase the blood pressure, etc. Another added benefit is its portability, allowing our educators to go to the crew’s location. We have found that most of our field staff appreciate the fact that their routine is not interrupted for education.

The newest advent is the placement of basic airway manikins at each of our stations. We vary the ages at each station–firstly due to budget reasons, and secondly so that there is a different challenge depending on where you are housed for the assigned timeframe. We make no requirements outside of encouragement for the field staff to practice the tactile skills involved in the use of video and direct laryngoscopy during intubation.

While not everyone on the staff will willingly take time to practice there are many that do, often creating a little bit of peer pressure that generates greater participation. It also creates an opportunity for field staff to discuss techniques and experiences that they have had with airway management, creating an environment of peer-to-peer discussion without the presence of management.

Education

Education can appear to be a very straight forward process: identify your goals, obtain the appropriate materials, and apply the lesson plan. We have found the process of educating our staff is the most difficult aspect while attempting to achieve the goals of 100% first pass success rate. The issues that we have identified regarding our field staff is that the education can often times become redundant.

While there are always better ways to optimize the entire RSI process, the basic principles of airway management have stayed the same. Optimization of hemodynamics, ventilation, and oxygenation form the foundation that the procedure has been built on for many years. The key question we find ourselves asking is how we keep our personnel engaged throughout the formal education process when we are repeating much of the same content. It is reasonable to assume that paramedics may not be fully engaged in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) classes or other mandatory recertification courses.

The solution we found is to continually modify our content and our approach to the education process. This has led to more engagement by our staff and improving results. Besides engaging by using new and realistic manikins, the latest advent has been the addition of teaching The Difficult Airway Class. PCHD EMS employees FP-C certified instructors for The Difficult Airway Class.7

This is our newest approach to the education of advanced airway management. It continues the process of adapting and changing the education to give our field staff a different prospective so that training does not get repetitive. The addition of field worn body cams has provided an avenue where our educators can use real life video of RSI attempts and analyze them during a classroom setting highlighting both positives and negatives.

It also allows educators to identify potential individuals’ weakness or lack of comprehension so that training can be specifically targeted. We constantly try to alternate the environment in which education is delivered with a mixture of classroom, simulation lab, and in the back of the ambulance training providing different experiences. All of this is implemented to provide an environment where our employees are engaged in the learning process and are not just going through the motions.

Empower

The only way to have a successful education program, regardless of if it is advanced airway management or CPR, is to have involvement from your employees. “Research has regularly demonstrated that when employees feel empowered at work, it is associated with stronger job performance, job satisfaction, and commitment to the organization.”8

You can encourage employees through actions, such as rewards or recognition, or by just a few positive words about their performance. While we apply some of these principles at PCHD EMS, our primary focus for engaging employees is through empowerment.

- We ask for their opinions if we are going to purchase new or replace old equipment with something else.

- We allow their input on the set up of our ambulances.

- We encourage discussion in all aspects of the organization, especially regarding airway management.

- We empower our employees to teach other local FROs, which continues to build on those relationships.

PCHD EMS is a strong believer in an open-door policy, whether that be management or the education department. We strongly encourage employees to voice their professional opinions without consequence to facilitate larger discussions. We empower our employees to get involved as much or as little as they feel comfortable. By taking this approach employees have a voice in the decision-making process, and they become invested into what we are trying to achieve.

This environment created by management greatly aids in the education of employees. They feel they have a stake in the service and when it succeeds, so do they. We also post everyone’s intubation success rates.

At first we, admittedly, were unsure if this was the correct approach. After speaking with several staff members, we decided that it could potentially be beneficial. The results are that everyone became competitive and pushed each other to become more proficient. Some individuals may get for or five intubations in the month and people want to know about the calls they encountered.

Some may miss a first pass intubation and people become engaged on why that happened and how they can learn from it. The important aspect is to make sure that it is utilized in only a positive way.

Evolve

The evolution of advanced airway management is a slow process that has not produced any profound changes to the basic principles of the procedure. Equipment used in the procedure consistently improves or adapts to better serve prehospital care approaches and improves patient outcomes. There has been a shift by some medical directors to apply delayed sequence intubation to all patients, regardless of their presentation, which can be argued for and against with evidence to validate both approaches.

The use of rapid sequence airway is another subsect of the airway umbrella that warrants further study and potentially more frequent application in the field. Whether it be equipment or different initial approaches, all of these must evolve slowly over time by way of evidence-based research before they can be implemented as a standard of practice.

While evolving, the process rarely leads to massive changes. PCHD EMS continues to implement new advents that both improve our procedure success rates and patient outcomes. Body worn cameras have had the greatest impact on us improving. They provide our educators with concrete data to help identify areas where we can improve our process by seeing its application in a real-world environment.

Our newest attempt to improve our process is by implementing some of the principles from Flight Bridge’s Damage Control RSI approach.9 We are refining our process to include advents to reduce ventilator acquired pneumonia by suctioning to the glottic opening every intubation and optimizing hemodynamics through OG tubes. We have also started tracking all our intubations using the Dash-1A criteria.

A radical evolution of advanced airway management is unlikely to take place anytime soon. However, that does not preclude any service from making adjustments, whether large or small, to improve our procedure success rates or patient outcomes. In education, evolution is a slow process, primarily involving small adjustments to the educational process.

There is no one way to approach education in emergency medical services. The only solution is an adaptive approach that is designed to implement new or old practices that encourage engagement by the entire service. The 7 E’s of Advanced Airway Management Education may not fit perfectly for every service, but the ability to adapt it to the resources you have at hand allow the template to be applied with modifications that fit any organizations resources.

Our experience has allowed us to achieve ninety-six percent or greater first pass success with the goals of 100% first pass success and Dash-1A scores. Educational programs are not unlike treating a critical patient in the prehospital environment. You are constantly evolving your diagnosis based on the evidence on hand until reach a diagnosis. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “Do what you can, where you are, with what you have.”

References

- Levitan, R. M. (2015, September 3).Timing resuscitation sequence intubation for critically ill patients. ACEP Now. https://www.acepnow.com/article/timing-resuscitation-sequence-intubation-for-critically-ill-patients/

- Thomas, J., Crowe, R., Schulz, K., Wang, H. E., de Oliveira Otto, M. C., Karfunkle, B., Boerwinkle, E., & Huebinger, R. (2024). Association Between Emergency Medical Service Agency Intubation Rate and Intubation Success. Annals of Emergency Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.11.005

- BEST EMS – About Us. (2024). https://bestems.org

- Hales, B. M., & Pronovost, P. J. (2006). The checklist—a tool for error management and performance improvement. Journal of Critical Care,21(3), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002

- Parker County Hospital District – About PCHD EMS. (2024). https://www.pchdtx.org

- Edwards, J. J., Nichols, A., & Bakerjian, D. (2023, March 1).Simulation Training. PSNet.

- The Difficult Airway Course – International Excellence in Airway Management. (2024). https://www.theairwaysite.com

- Lee, A., Willis, S., & Wei Tian, A. (2018, March 2).When Empowering Employees Works, and When It Doesn’t. Harvard Business Review.

- Flight Bridge ED. (2024).Damage Control RSI – Advanced Airway Management. https://flightbridgeed.com/courses/91353/

Terry Riddle, BSN, BHS, FP-C, works for Parker County Hospital District EMS as a critical care paramedic and supervisor. He, along with a supportive team, engage in airway and critical care training, while also partnering with University of North Texas Health Science Center on prehospital medical research.