Shutterstock/Frankspu

To borrow from Dr. Scott Weingart’s phrasing of “bringing upstairs care downstairs” as it pertains to critical care in the emergency department, EMS organizations often are attempting to extrapolate ICU and ER studies into the prehospital environment and reproduce their outcomes. Better stated, we are making a valiant attempt at bringing the care provided inside the hospital outside of the hospital to the living rooms and roadsides of the communities in which they serve.

There is a paucity of high-quality research on airway management in the prehospital environment, and while some robust and potentially practice changing papers do exist, we often find some variation of the following Q&A:

Question: “Are outcomes better when we do XYZ in prehospital airway management?”

Answer: “Maybe, it depends. More studies are needed….”

Sometimes we can get it “right” and sometimes we “miss” even though we executed well and did it “right.” We bring all of the “proven” and evidence-based interventions to bear, but still have trouble re-creating the results from the papers that we based our clinical decisions on.

The confounder to many of these situations is the operational environment in which the procedure is being executed. Within prehospital operational contexts are elements that (generally) do not negatively impact performance in the hospital but are known factors of human performance outside of the hospital. It begs the question of how can we hope to get the best outcome possible, while operating in the worst possible conditions to enable them?

The Prehospital Operational Environment

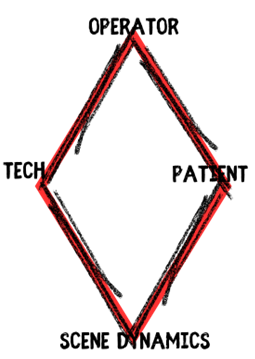

The environment in which prehospital clinicians operate is influenced by four primary contexts: the operator, the patient, the scene dynamics, and the technology available. Each of these presents a specific set of challenges on their own, but when these operational elements develop feedback loops with each other and interact with each other, the contextual dynamics can become quite complicated. It is why our world and our patient encounters are so dissimilar day in and day out. It also accounts for some of the variability in our results and outcomes in prehospital airway management.

Operator Dynamics

Each individual clinician brings a certain dynamic to an airway management situation. Their training, level of experience, and recency of experience all come together to build two main determinates of performance: confidence and ability. It is one thing to be able to do something and have proven competency in a testing situation. It is something wholly different to have the confidence (from their training and experience) to effectively execute the necessary procedures under the duress of an emergency scene. Other factors such as fatigue and nutrition can also impact an individual operator’s performance.

Patient Dynamics

Each patient presents two specific difficulties to prehospital clinicians: physical and physiologic. Some of the physical difficulties of airway management can be navigated and defeated with tools such as video laryngoscopes, use of a bougie, or selecting another procedure (other than intubation).1-2 Perhaps even simpler maneuvers like elevating the ear-to-sternal notch or ramping the patient can overcome some of the difficulties with aligning the airway anatomy.1-4 But alas, a patient who is trapped in a vehicle and requires immediate airway management makes these simple maneuvers difficult to execute in such confined spaces.

Roughly five years ago the term “physiologically difficult airways” was penned by Jarrod Mosier.2 Physiologic difficulty in airway management is defined as peri/post intubation hypotension and peri/post intubation hypoxia.2-4 Each are known to contribute to airway mortality and morbidity, but when they co-exist things become much more problematic. Pre-oxygenation is a top priority to avoid one of the worst complications of airway management, anoxic brain injury.3 But close attention must be paid to the patient’s hemodynamics in order to avoid hypotension, which is the number one predictor of post-intubation hemodynamic collapse.2,4 Patients who present in shock, outside of the hospital, and require airway management represent some of the highest risk airway management scenarios for paramedics. The out-of-hospital environment complicates the picture due to a lack of available resources to respond to the physiologic derangement.

Scene Dynamics

Challenge 1: The Sensory Assault on the Operator

An emergency scene is a full assault on the human body’s sensory system. Ambient temperature, lighting, noise, the visual stimulus of seeing an injured fellow human being, and the oppressive odors can distract even the most seasoned prehospital veteran and sabotage their performance. Add to that, poor nutrition, dehydration, fatigue (from a number of causes), and the emotional hangover from the last call (or calls); and it is really no surprise at all that the complexities and difficulties of airway management are made even more apparent in the prehospital operational environment.

Both individuals and organizations alike can (and have) implemented several mitigation tools that range from crew rest cycles to box breathing (aka tactical breathing). But, like Dr. Fazan Arshad and Tony Robbins say, it is not a lack of resources that sabotages our performance; rather it is a lack of resourcefulness. Meaning, we are sometimes so immediately overwhelmed or caught up in the stimulus that we fail to have the presence of mind to utilize the available mitigation strategies.

So, place a fatigued, poorly hydrated paramedic onto the scene of an emergency completely assaulting their nervous system, with a life hanging in the balance; and we can see where some of our difficulty comes from when attempting to bring inside care outside.

Challenge 2: Time Pressure

The one pressure that remains undefeated for creating high stress environments is time. Prehospital teams not only operate under the same physiologic time pressure that clinical teams do inside the hospital when treating unstable patients, but they have an operational time pressure not shared by the clinicians inside the hospital. In that, they still have to deliver the patient to definitive care.

Prehospital teams often encounter airway management situations that are commonly classified as “forced to act” situations. They are classified as such because the patient, for any number of reasons, has no patent airway and it must not only be opened and managed, but protected. While not unique to prehospital teams, these “force to act situations” can be exacerbated by the other operational complexities that exists in the prehospital environment.

Technology

The presence of certain technology on the scene can help mitigate and address the physical or physiologic derangements that can present in the prehospital environment. But the need for redundancies and currency in those redundancies necessitate the highest level of preparation and training.

But prehospital teams do not have all of the equipment that an anesthesiologists or emergency department physician would have available to them. They are limited by what they carry in bags to the patient’s side. While redundant systems and technologies are essential to high performance and good outcomes, the environmental context limits what can be carried to the scene and/or issues to teams.

Equipment reliability and durability is yet another factor that can complicate things in the prehospital environment. Some of the sharpest and brightest screens on video laryngoscopes exists on equipment that is not durable enough for the prehospital environment.

Conclusion

These four dynamics can independently or concomitantly present prehospital teams with a number of difficulties that may or may not be overcome or mitigated in the prehospital operational environment. Many risk mitigation strategies exists and are available to EMS organizations that can be implemented as part of an airway management system, designed to address these four domains of operational complexity.

References

1.J arvis JL, Gonzales J, Johns D, Sager L. Implementation of a Clinical Bundle to Reduce Out-of-Hospital Peri-intubation Hypoxia. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Sep;72(3):272-279.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.044. Epub 2018 Mar 9. PMID: 29530653.

2. Mosier JM, Sakles JC, Law JA, Brown CA 3rd, Brindley PG. Tracheal Intubation in the Critically Ill. Where We Came from and Where We Should Go. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 1;201(7):775-788. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1636CI. PMID: 31895986.

3. Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Mar;59(3):165-75.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.002. Epub 2011 Nov 3. PMID: 22050948.

4. Mosier JM. Physiologically difficult airway in critically ill patients: winning the race between haemoglobin desaturation and tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2020 Jul;125(1):e1-e4. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.001. Epub 2019 Dec 24. PMID: 31882262.

5. Jaber S, Jung B, Corne P, Sebbane M, Muller L, Chanques G, Verzilli D, Jonquet O, Eledjam JJ, Lefrant JY. An intervention to decrease complications related to endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Intensive Care Med. 2010 Feb;36(2):248-55. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1717-8. Epub 2009 Nov 17. PMID: 19921148.

6. April MD, Arana A, Reynolds JC, Carlson JN, Davis WT, Schauer SG, Oliver JJ, Summers SM, Long B, Walls RM, Brown CA 3rd; NEAR Investigators. Peri-intubation cardiac arrest in the Emergency Department: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) study. Resuscitation. 2021 May;162:403-411. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.039. Epub 2021 Mar 5. PMID: 33684505.

Cody Winniford is a flight paramedic and base manager in Baltimore, MD. He has a passion for sharing his professional experience in EMS and management. Cody’s clinical and leadership development background spans both military and civilian settings and has served in several capacities as a leader and prehospital clinician. He specializes in air medical and critical care transport, as well as organizational development and leadership development. He is an active speaker on various leadership and clinical topics and is an established and successful educator for prehospital clinicians of all levels. He has a passion for human performance improvement and the mental health and performance aspects of prehospital care.