Introduction

Emergency endotracheal intubation of a critically ill patient with a difficult airway can pose significant challenges and places the patient at high-risk of complications. The difficult airway is defined as body fluids obscuring the laryngeal view, airway obstruction or edema, obesity, short neck, small mandible, large tongue, facial trauma, stiff neck or the need for cervical spine immobilization.1 Additional attributes such as laryngoscopy illumination failure, angioedema, epiglottitis, pharyngitis, hemorrhagic hamburger-like oropharynx, false cords obscuring the true vocal cords and subglottic stenosis can make endotracheal intubation almost impossible.

When performing intubation on a patient with a difficult airway, the glottis may be visualized using video laryngoscopy because it can overcome the limitations of direct line of site. However, this does not mean that the endotracheal tube will be able to be advanced into the trachea because there may be an acute angle that impairs the path as the operator attempts to advance the endotracheal tube.5 Careful selection of sedatives and paralytics should occur because if the endotracheal tube cannot be advanced into the trachea the patient may die.

More from EMS Airway

- Decreasing COVID-19 Patient Risk and Improving Operator Safety with the AIROD® During Endotracheal Intubation

- Increasing Intubation First-Attempt Success Rates in Patients of All Ages

- Prehospital Critical Care for COVID-19 Patients

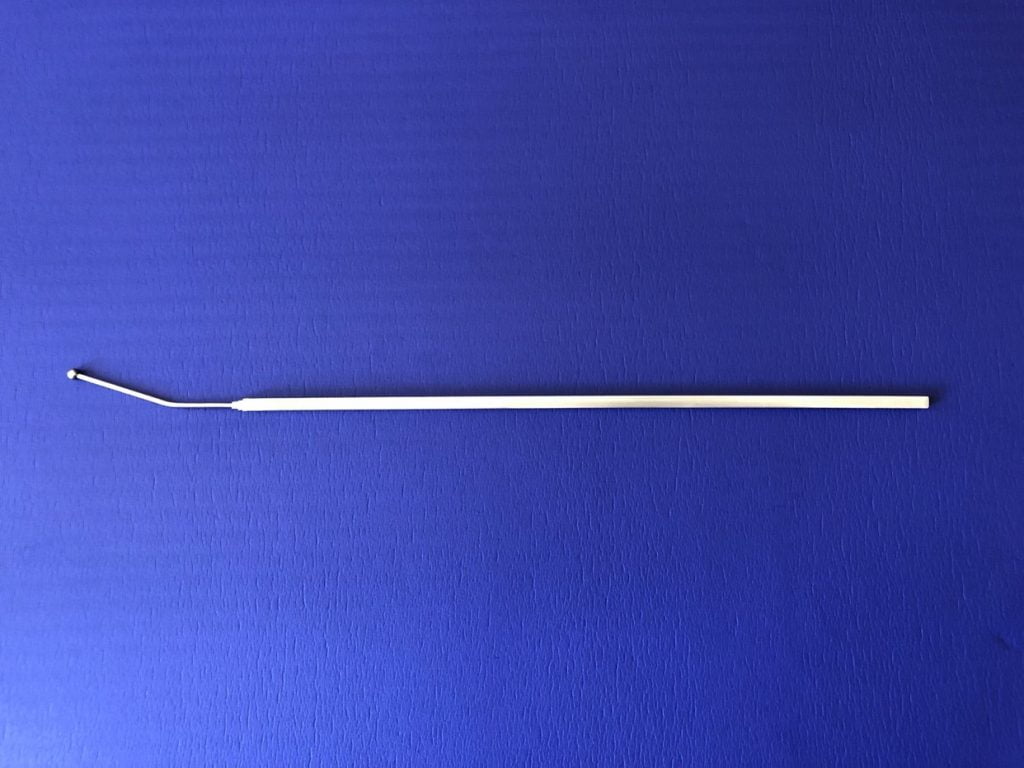

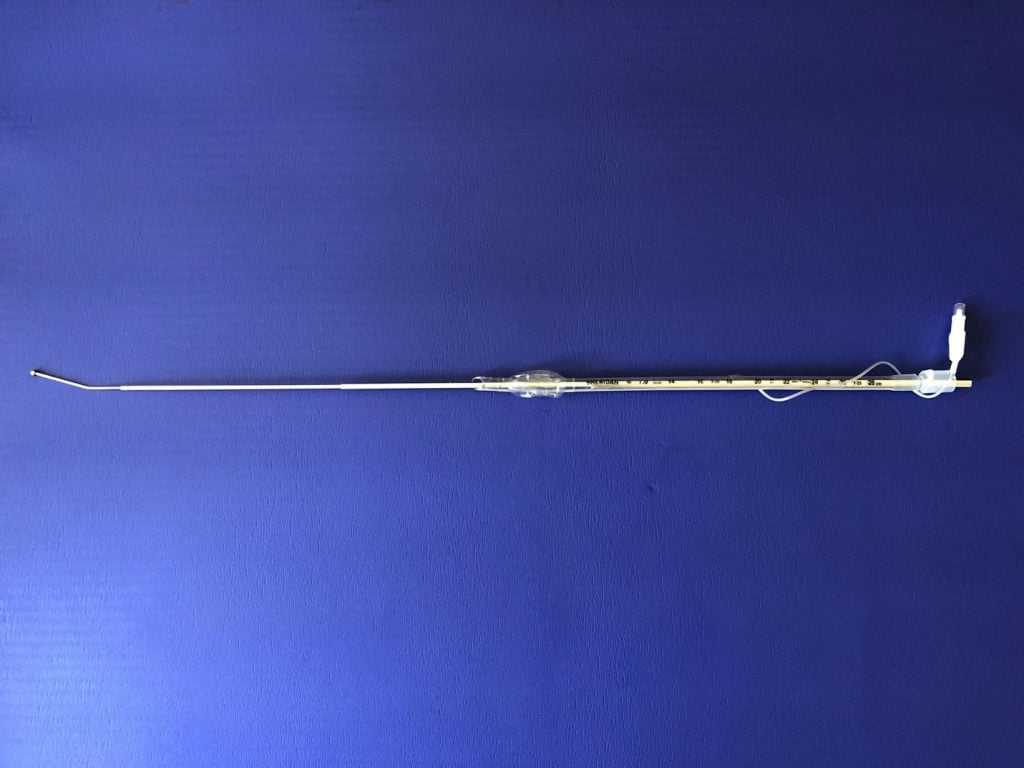

The AIROD® has proved that it can improve the view of the glottis by manipulation of the oropharyngeal tissue as well as facilitate placement of an endotracheal tube successfully into the trachea without causing significant trauma to the oropharynx or tracheobronchial tree.6,7 The AIROD® is a single-use telescoping rigid bougie that can fit in a pocket or drawer (Figure 1). It can be expanded quickly and used as an endotracheal tube introducer (Figure 2). The following is a case study demonstrating the ability of the AIROD®, along with direct laryngoscopy, to manipulate oropharyngeal tissue as well as bloody secretions to expose the true vocal cords and to guide an endotracheal tube safely into the trachea for successful intubation of a patient with a difficult airway without causing significant oropharyngeal trauma or having to perform a high-risk emergency cricothyrotomy.

Figure 1. AIROD® in the closed position.

Figure 2. AIROD® in the extended and locked position.

Case

The case involves a 28-year-old, 5-foot-9 inches tall male, who weighs 97 kg and has a body mass index of 31.5. The patient has a past medical history significant for alcoholic cardiomyopathy and esophageal varices, is currently drinking two liters of vodka daily. He also drank hand sanitizer. He developed acute shortness of breath and felt that his “throat was closing.” He developed very severe stridor with severe respiratory distress and was transferred to the intensive care unit. Audible stridor could be heard upon his arrival. He was in severe respiratory failure sitting up in the tripod position and very anxious. He was drooling and his secretions were bloody. He was unable to produce sound when he attempted to speak. He was placed on a non-rebreather mask (NRB) at 15 L/min with an FiO2 of 100%. He was obese with a large neck with limited mobility, a mouth opening of only 2 cm, protruding large tongue, full set of teeth, and micrognathia with very severe stridor barely moving any air.

He was given 4 mg IV midazolam for severe agitation. Surgical tools were prepared in case of the need for an emergency cricothyrotomy. He was given 100 mg IV propofol then laid flat and positioned into the sniffing position quickly. Bag-valve mask ventilation was performed achieving an SpO2 of 100%. An additional 100 mg IV propofol was given. He was not paralyzed in hopes that his ventilation would help identify the glottis by maintaining airflow through the vocal cords during laryngoscopy. A Miller 4 blade barely lifted the tongue when fresh blood was encountered. The blade was advanced gently, and bloody secretions were suctioned revealing a grade 4 view. A crowded anterior hemorrhagic hamburger-like oropharynx, bleeding with mucosal sloughing and false cords were encountered after significant manipulation of the tracheal cartilage and cricoid pressure.

The AIROD® was used to probe the oropharynx and locate the epiglottis then used to gently lift the epiglottis without causing significant bleeding. The AIROD® was then advanced 3 cm into the hamburger-like oropharynx without visualizing the vocal cords, followed by a 6.5 endotracheal tube that had been pre-loaded onto to the AIROD®. The AIROD® was removed intact. A bag-valve was connected to the endotracheal tube and ventilation was performed with no color change on the CO2 detector after a few breaths. The endotracheal tube was removed as it was suspected that it had been placed in the esophagus. Bag-valve mask ventilation was performed achieving an SpO2 of 100%. The AIROD® was pre-loaded with a 7.0 endotracheal tube. A second-attempt revealed a 2 mm air bubble.

The AIROD® was advanced toward the tiny air bubble. The AIROD® was used to probe the glottis and used to peel back the false cords revealing a glimpse of the right vocal cord. This was followed by advancement of the AIROD® 3 cm into the trachea. A 7.0 endotracheal tube was slowly advanced into the trachea. No assistant held the AIROD®. The endotracheal balloon was inflated and the AIROD® removed intact without any evidence of acute oropharyngeal trauma. Bronchoscopy revealed no tracheobronchial trauma. Nasopharyngeal swab confirmed acute adenoviral necrotizing pharyngitis. The patient was extubated within a week and walked out of the hospital a few days later.

Discussion

This patient had characteristics of a difficult airway: obese with a large neck with limited mobility, a mouth opening of only 2 cm, protruding large tongue, full set of teeth, micrognathia, and a crowded, hamburger-like anterior oropharynx with very severe stridor barely moving any air. Prior to manipulation of the oropharynx with the AIROD® only a grade 4 view (epiglottis and glottis not seen) was visualized. His oropharynx was actively bleeding with mucosal sloughing. He required significant manipulation of the tracheal cartilage and cricoid pressure just to see the oropharynx. Initial placement of the endotracheal tube was into the esophagus because the glottis could not be identified.

The failed first-attempt intubation helped identify many factors that could have led to an emergency cricothyrotomy: very severe stridor barely moving any air, inability to swallow copious bloody secretions, obesity, large neck with limited mobility, mouth opening of only 2 cm, protruding large tongue, full set of teeth, micrognathia, crowded hemorrhaging hamburger-like anterior oropharynx with mucosal sloughing, and false cords. Because he was not paralyzed, he was able to take a breath and create a tiny 2 mm air bubble. The AIROD® was advanced toward the air bubble and then used to manipulate the damaged tissue to improve the view of the airway, thereby preventing the need for an emergency cricothyrotomy.

The AIROD® was used to lift the epiglottis, identify the anterior area where the glottis was located and used to successfully probe that area to reveal the vocal cords. Unlike a plastic bougie, the AIROD® is rigid enough to displace soft tissue but also malleable allowing for flexion without breaking. These characteristics allow the AIROD® to move oropharyngeal structures out of the operator’s line of sight thus improving the view of the glottis. Because of its rigidity and specialized 20-degree spherical tip, the AIROD® is less likely to catch on the arytenoid cartilage leading to inferior placement into the esophagus, which can happen with the plastic bougie.

Emergency endotracheal intubation of a difficult airway is one of the riskiest lifesaving procedures performed by medical personnel. Preparation is paramount to avoid adverse outcomes such as death.7 This case study demonstrates the effectiveness of using the AIROD® on patients with difficult airways. The AIROD® overcomes the limitations of laryngoscopy by acting not only as an endotracheal tube introducer but also as a surgical tool that can be used to manipulate the oropharyngeal tissue, thus improving visualization of the vocal cords and facilitating safe access to the trachea.

Conflicts of Interest: Evan D. Schmitz, M.D. is the inventor of AIROD®.

Kevin Park, MD, MBA, FCCP has no conflicts of interest.

Support: The authors received no funding.

The authors thank Carol Fountain and Abra Gibson for their editorial comments.

References

- Driver B, Prekkar M, Klein L, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(21):2179-2189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6496.

- Higgs A, McGrath A, Goddard C, et al. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J of Anaesth. 2018 Feb;120(2):323-352. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.021.

- Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant JY, et al. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2355-2361.

- Widmeier K. Prehospital management of Difficult Airways. JEMS. 2016 May;5(41).

- Levitan R, Heitz, J, Sweeney M, Cooper R. The Complexities of Tracheal Intubation With Direct Laryngoscopy and Alternative Intubation Devices. Acad Emerg Med. 2003 Jul; 10(7):717-24.

- Schmitz E. AIROD® Case Series: A new bougie for endotracheal intubation. J Emerg Trauma Care. 2020;5(2):20. doi: 10.36648/trauma-care.5.2.20.

- Schmitz E. Decreasing COVID-19 patient risk and improving operator safety with the ARIOD® during endotracheal intubation. JEMS. EMSAirway. 11/2020.

- Brown CA III, et al; NEAR III Investigators. Techniques, success, and adverse events of emergency department adult intubations. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(4):363-370.

Evan D. Schmitz, MD is a board certified pulmonary and critical care physician and the inventor of the AIROD®.

Dr. Kitae Kevin Park is a pulmonary and critical care physician. He obtained his medical degree at Saba University School of Medicine. He completed his residency in internal medicine at UNDNJ-NJMS, then went on to complete his fellowship at Carl T. Hayden VA Medical Center in pulmonary and critical care. He has served as medical director in multiple ICU programs in Southern California. Dr. Park continues to focus on delivery of healthcare in underserved areas.