Shutterstock/Frankspu

By Lew Steinberg, MPA, NRP

You arrive at the scene of a pediatric emergency to find a five-year old child in cardiac arrest. Recent training and your pediatric guidelines recommend using a bag-valve-mask (BVM) manual resuscitator for ventilation with the addition of an oropharyngeal airway (OPA).

As you continue ventilation while also considering potential causes of the arrest, the patient begins to vomit copious amounts of their now former gastric contents. Despite repeated suctioning, it becomes increasingly difficult to ensure an unobstructed airway.

You recognize the need for advanced airway placement and quickly ponder your next choice, a supraglottic airway (SGA), which is the next step in your guidelines, or endotracheal intubation.

Everyone in the prehospital arena is involved in some degree of airway management. After ensuring scene safety and possibly providing hemorrhage control, airway control remains a high priority. Much as we learned our ABCs in childhood, they also became baked into our early patient care education.

There have been published studies supporting the efficacy of one method or another for airway management. Given the many “fact-based” opinions on the topic, field providers may be left to wonder how to determine the best method to use.

The simple answer is that there is no ideal method for every situation. It is up to your clinical judgment as to the best care for that patient, given the particular situation.

A simple method that can help answer the question of “how” is to again go back to our early in life education and ask the five W’s: who, what, when, where and why.

Who is performing the airway management and who is on the receiving end? A highly skilled and experienced provider may approach airway management differently than a novice. Someone who has intubated several children and regularly practices the skill will likely be more confident than one who has not.

An obese patient with a short, thick neck will likely present a greater challenge than one with a long, slender one. The airway of small children has different anatomical features than an adult that the provider must be aware of before being surprised at the time of need.

Additionally, some systems have relatively few medics who gain far more individual experience than those who frequently respond with a half-dozen advanced life support providers and therefore have fewer opportunities to practice and maintain less used skills.

What is available to use? There are services that do not have endotracheal intubation available; some have actually removed it. While video laryngoscopy has been available for years, the devices are still not universally accessible and are often not equipped for smaller children.

Hopefully, every service has properly sized BVMs and basic airway adjuncts, but may not have all sizes of intermediate, supraglottic airways available. Having great equipment is only half of the equation; the individual using it must be comfortable with its proper operation.

When is the procedure required? While initial care is generally provided using basic devices, situations may be fluid (no pun intended) or dictate other methods. Years ago, I treated a patient with very limited access who was pinned under the front axle of a vehicle and in respiratory arrest.

Luckily, that was in the days when oxygen powered demand valves with manual ventilation capability were routinely carried. I was able to barely access his face to provide effective ventilation. There was inadequate space for a BVM or any other adjuncts.

Once he was removed, thanks to a passing tow truck who was able to lift the vehicle before we could, advanced procedures became possible. The initial care provided may differ from what is indicated as the call progresses and the location changes.

Where is the patient? Are they located in a confined space, as above, pinned in wreckage or a collapse, in the back of your vehicle, or one of many other locations?

When you arrive at the emergency room, the physician will likely be surrounded by multiple providers with varying levels of training, a bed that can be raised in height and a well-lit room in a controlled environment. I do not remember performing much, if any, field care in that kind of setting.

Why are you managing the airway? Ventilating a suspected narcotic overdose patient, who is likely to begin breathing after naloxone administration, is a very different scenario than an ongoing cardiac arrest.

Providing an airway for ventilation is a very different situation than securing one that requires protection from repeated intrusion of vomit, blood or another invasive substance.

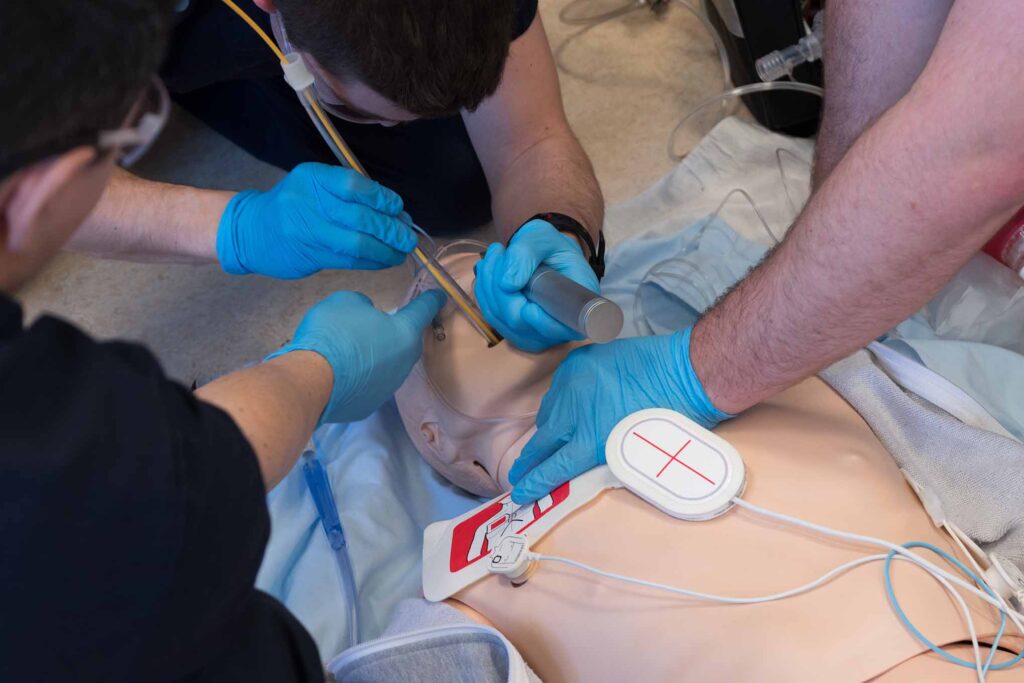

What about the five-year old in cardiac arrest from the opening scenario? We know that pediatric patients may require a different approach and are fortunate to have an experienced provider who has access to and is comfortable with pediatric video laryngoscopy assisted intubation.

Despite initial success, continued BVM ventilation proves challenging due to the ongoing fluid challenge presented by flowing gastric contents; the progression of this incident highlighted the need for more advanced procedures.

Fortunately, the patient is in an open space with good access and all required equipment available. Since the reason for intervention changed from merely ventilating to include the need for advanced airway protection, a change in procedure was warranted.

As a result of your care, the child was successfully resuscitated while avoiding the potentially fatal secondary complication of aspiration pneumonia.

The simple response as to the best method of airway management depends on the answer to all of the questions listed above. There is no universal right or wrong; it is a situational decision.

Editor’s Note: This commentary reflects the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of EMS Airway.

About the Author

Lew Steinberg has been involved in EMS since 1971, when he was initially certified as an EMT, and is also a former fire chief. He spent several of those years, often simultaneously, in both prehospital and hospital-based care, and remains active in paramedic training.

Exclusive feature content from thought leaders in airway management.